So simple, and yet so complicated <a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/tamaki/374797/">Tamaki</a>/Flickr

As I’ve reported before, the US poultry industry has a disturbing habit of feeding arsenic to chickens. Arsenic, it turns out, helps control a common bug that infects chicken meat, and also gives chicken flesh a pink hue, which the industry thinks consumers want. Is all that arsenic making it into our food supply? It appears to be doing so—both in chicken meat and in, of all things, rice. In a just released report, Consumer Reports says it found significant levels of arsenic in a variety of US rice products—including in brown rice and organic rice, and in rice-based kids’ products like cereal and even baby formula. Driving the point home, CR‘s analysis of a major population study found that people who consume a serving of rice get a 44 percent spike in the arsenic level in their urine.

Rice is particularly effective at picking up arsenic from soil, CR reports, “in part because it is one of the only major crops grown in water-flooded conditions, which allow arsenic to be more easily taken up by its roots and stored in the grains.”

Arsenic, CR reports, is classified by the International Agency for Research on Cancer as a “group 1” carcinogen—meaning that it’s among the globe’s most potent cancer inducers. And getting regular exposure to even small amounts of it can be troubling. Here’s CR:

No federal limit exists for arsenic in most foods, but the standard for drinking water is 10 parts per billion. Keep in mind: That level is twice the 5 ppb that the EPA originally proposed and that New Jersey actually established. Using the 5 ppb standard in our study, we found that a single serving of some rices could give an average adult almost one and a half times the inorganic arsenic he or she would get from a whole day’s consumption of water, about 1 liter.

So what does arsenic-laced rice have to do with feeding arsenic to chicken? Well, it’s impossible to tell the ultimate source of the arsenic that gets taken up by rice, and it’s true, as the US Rice Federation says on its web site, that it is “a naturally occurring element in soil and water.” But as Nature reported in 2005, US rice carries “1.4 to 5 times more arsenic than rice from Europe, India and Bangladesh.” What gives? Here in the United States, we’ve added massive amounts of arsenic to the environment over the decades. How much? Here’s Consumer Reports:

The U.S. is the world’s leading user of arsenic, and since 1910, about 1.6 million tons have been used for agricultural and industrial purposes, about half of it only since the mid-’60s.

Much of that came in the form of arsenate pesticides, which until they were banned in the 1980s were commonly used on cotton fields—where, according to Consumer Reports, residues of those pesticides linger today. And US cotton and rice price production have significant overlap in the mid-South region. “Quite a lot of land in Mississippi and Arkansas that previously grew cotton is now used for rice cultivation,” Nature reports. And indeed, when rice first began to be grown on former cotton land, the crop did poorly, laid low by “an arsenic-induced disease known as straighthead,” Nature reports. Rather than encourage farmers to abandon the project of growing a food crop in arsenic-rich soil, CR adds, USDA “invested in research to breed types of rice that can withstand arsenic.” Of course, breeding rice varieties that could survive in arsenic-rich soil also meant breeding rice that could take up plenty of arsenic.

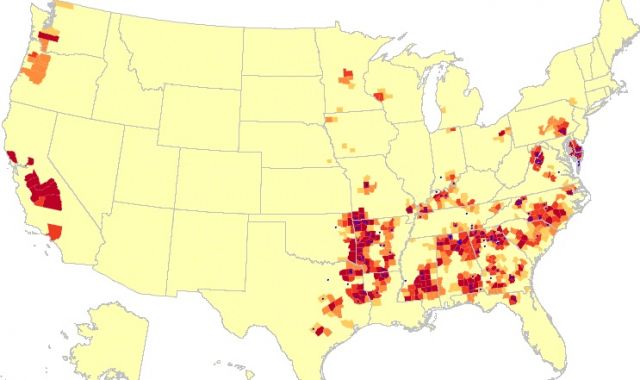

But residues from a long-banned pesticide aren’t the only source of arsenic in rice country. Industrial-scale poultry farming, with its long-time reliance on arsenic-laced feed, provides another. Consider this map of depicting the concentration of industrial-scale chicken farming, prepared by Food and Water Watch. (The darker the color, the higher the density of poultry facilities, with the color red denoting “extreme” concentration.)

Geographical concentration of poultry production Food & Water Watch

Geographical concentration of poultry production Food & Water Watch

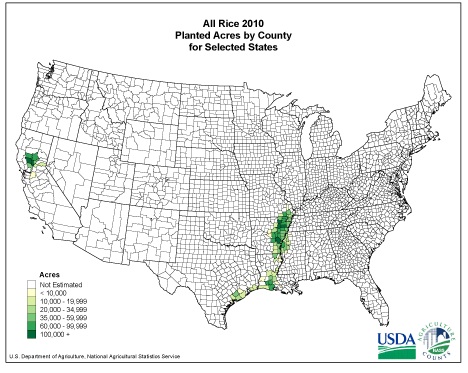

Now look at this USDA map showing US rice production.

US rice production USDA

US rice production USDA

As you can see, both have overlap in the Central California and mid-South regions. Now, the arsenic in poultry feed is in its non-toxic organic state. But it can transform into the carcinogenic inorganic state both in the chickens’ guts and also in the environment, when arsenic-laced manure comes into contact with the elements. “Arsenic in poultry manure is rapidly converted into an inorganic form that is highly water soluble and capable of moving into surface and ground water,” write Keeve E. Nachman and Robert S. Lawrence of the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future.

And to get rid of the massive amounts of poultry litter generated by concentrated farming, the poultry industry applies as much of it as possible to nearby fields as a fertilizer—where arsenic accumulates in the soil, a 2010 study by USDA researchers found.

And not surprisingly, large-scale rice farmers make use of “chicken litter”—chicken manure, plus bedding and spilled feed—as a fertilizer. Precise figures on just how much chicken litter ends up in rice fields don’t exist, because the federal government doesn’t track the practice.

But anecdotal evidence suggests it’s common. “Chicken litter: smell of success,” declares a 2010 headline in Delta Farm Press, a trade journal, in an article on the practice of using chicken litter on Arkansas rice farms. Rice farmers there commonly use the stuff at a rate of between one and three tons per acre, Delta Farm Press reports. In this 2007 paper, a USDA scientist declares that the stuff improves “overall rice growth and yield,” and also boosts “tillering,” which is the ability of rice plants to grow grain-bearing branches. And a 2010 study by the Mississippi Agriculture Extension reports that as synthetic fertilizer prices rise, “more and more growers” are turning to the state’s abundant supply of chicken litter.

And arsenic can make its way from factory chicken house to rice field by leaching into irrigation water. According to Food and Water Watch, in another poultry intensive region, the Delmarva peninsula that forms Chesapeake Bay, arsenic is routinely found in household wells, at “up to 13 times the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) tolerance limit.” Thankfully, no rice is produced in the Delmarva area, but as the above map shows, the rice-growing in the mid-South region has a similar concentration of poultry farming.

Now, unfortunately, chicken litter from large industrial operations is also commonly used as fertilizer on organic farms—which may explain why several organic products, like Lundberg brand short-grain organic brown rice (which I have in my pantry, via the bulk section of my local food co-op), appeared on CR‘s list with relatively high levels of arsenic. To its credit, however, Lundberg Family Farms, a major California producer of organic rice, is taking the issue seriously—it is “testing more than 200 samples of the many varieties of rice in its supply chain and plans to share the results with FDA scientists,” CR reports. The conventional rice industry, meanwhile, is mostly in denial, though USA Rice Federation did tell Consumer Reports that it is “working with the FDA and the EPA as they examine and assess arsenic levels in food and has supplied rice samples to those agencies for research.”

What’s the takeaway from all of this? To avoid excessive exposure to arsenic, Consumer Reports recommends that adults limit their rice intake to two quarter-cup servings per week; children, they say, should get just 1.25 servings per week. In the long term, Urvashi Rangan, director of safety and sustainability at Consumer Reports, told me, “what we’d really like to see happen is for the FDA to get serious about getting arsenic out of chicken feed.” So far, the agency has been working with the ag-pharmaceutical industry to “voluntarily” stop the practice, but there remain dozens of arsenic-based feed additives approved for use on poultry, she said.