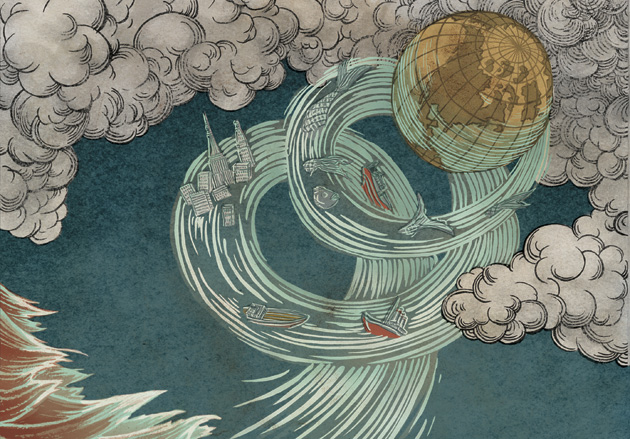

<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/oneeighteen/244725322/">OneEighteen</a>/Flickr

Back in 2006, a team of scientists from Canada, the United States, Sweden, and Panama published a landmark report in the prestigious journal Science on the state of the oceans. The researchers highlighted what they called an “ongoing erosion of diversity” in sea life that, if left unchecked, would lead to the “collapse of all taxa currently being fished by the mid-21st century.”

Stripped of scientese, what the report described was the real possibility of the ocean as a vast, fetid gray zone, not quite dead but no longer able to provide a significant amount of food to humanity. And not in some unimaginably distant future, but rather in just four short decades, around the time when your aughts-era infant will reach middle age.

When the report dropped, it grabbed attention in the eco-foodie world like a great white shark sunning its dorsal fin in the shallows off a crowded beach. I was just beginning to write about food politics at the time, and the Science study jolted me from my land-locked fixations and opened the ocean as a rich and urgent topic.

Not only do the oceans cover more than two-thirds of the planet, but they’re also home to 90 percent of the planet’s living biomass. Snuffing out their astonishing biodiversity would have unpredictable consequences for we creatures who dwell on the earth’s relatively rare swaths of dry land. Surely, I thought at the time, the Science paper would spark a global push to heal what ails that murky, saline region that surrounds us.

So, six years after the study’s publication, how are the oceans doing? Have the globe’s leaders acted in decisive fashion to protect them? I put the question to the ingeniously named Boris Worm, a German-born marine ecologist at Canada’s Dalhousie University and a co-author of the Science paper, in a phone interview. Speaking in that precise, clear English common to German intellectuals—think the filmmaker Werner Herzog—Worm gave a chilling answer: “The loss of [oceanic] biodiversity continues at a pace that’s not slowing down,” he said. “On average, the condition of the oceans continues to get worse.”

Ocean ecologist Boris Worm, in action. Worm wanted to make sure I understood his famous study. He and his team were applying to the oceans what I think of as the central insight of ecology: that an ecosystem’s health is directly related to the diversity of creatures that live within it. The wider variety of organisms that interact within an ecosystem, the more healthy and resilient it is; the less biodiverse, the more vulnerable and prone to unravelling.

Ocean ecologist Boris Worm, in action. Worm wanted to make sure I understood his famous study. He and his team were applying to the oceans what I think of as the central insight of ecology: that an ecosystem’s health is directly related to the diversity of creatures that live within it. The wider variety of organisms that interact within an ecosystem, the more healthy and resilient it is; the less biodiverse, the more vulnerable and prone to unravelling.

Worm and his collaborators, who worked for four years on the project, analyzed the results of 32 controlled experiments, crunched data from 12 coastal ecosystems, and combed global fisheries records kept by the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization. The results confirmed their hypothesis that biodiversity is central to the oceans’ health—and that loss of biodiversity threatens to send oceanic populations into a catastrophic plunge.

They show that biodiversity decline accelerated dramatically with the rise of industrialization in the early 19th century, which gave rise to increasingly efficient fishing techniques as well as a deluge of pollution into oceans. As these human-induced factors strip the ocean of fish at rates faster than they can reproduce while simultaneously degrading their habitats, ecosystems become increasingly fragile, leading to a downward spiral.

And it’s not just at the fish counter that we’ll feel the effects. “When the study came out, I was surprised that media attention focused only on the fishery effects,” Worm told me. But oceans provide other services too: coastal wetlands filter pollution and provide a critical buffer against flooding, for example, and beaches provide attractive places for humans and other species to hang out. All of that, too, is under threat from biodiversity loss, Worm and his team found.

Now, on the hopeful side, Worm and his collaborators also found that the converse to their hypothesis is true: that when oceanic ecosystems are protected, biodiversity reemerges and ecosystems grow more robust and productive.

And indeed, while stressing that “on average” the oceans continue to lose biodiversity at an alarming rate, Worm said that since the publication of his report, several coastal regions had taken effective steps to protect their seascapes—including effectively managing their fisheries—and were already reaping the rewards. He cited New Zealand, Alaska, and California as prime examples. The latter state is now experiencing a revival in its salmon fishery, which by 2008 had been driven to near collapse.

Other trends that cheer Worm are the move by Caribbean countries to protect sharks, which had been vastly overfished and play a vital role in ecosystems; the expansion of marine reserves where no fishing at all is allowed; and moves by big US and European retailers to only buy seafood from fisheries that have been certified as sustainable by groups like the Marine Stewardship Council. The certification process is far from perfect, Worm said, but “it’s a signal in the right direction.”

But none of these hopeful initiatives are spreading widely enough, quickly enough, to stem the overall erosion of biodiversity, he said. And in the absence of strong global rules on fishery management, regional successes like California can simply displace overfishing to other areas. He cited the example of Africa, whose largely unregulated coastal waters are being pillaged to provide fish for people in Europe and Asia, where fishing regulations are stronger. As with climate change, this is a global problem that requires “globally coordinated action,” Worm said.

I asked Worm about land-based threats to the oceans that have nothing to do with fishery management. Climate change, for example, is causing the acidification of the ocean, which in turn harms all species with carbonate shells—everything from the corals that make habitat-forming reefs to the calcareous plankton that feed deep-sea fish to oysters and clams. Here again, Worm returned to nurturing biodiversity as a critical factor.

“Acidification is a shock, and biodiverse ecosystems are much more robust in the face of such shocks, better able to adjust to them,” he said. In his view, acidification will not likely prove to be a deciding factor in whether the oceans survive as vital ecosystems over the next four decades. But he added a caveat: if acidification intensifies enough to devastate coral reefs, as some experts warn it might, then it could prove disastrous. “Coral reefs are cradles of biodiversity in coastal waters,” he said. And for Worm, biodiversity is everything.

I asked him if there is a point of no return for oceanic biodiversity. “Yes,” he said, “but it’s impossible to know precisely where it is.” He likened humanity’s current relationship to the ocean to driving an unfamiliar car over unknown terrain at night while steadily losing vital functions like headlights and windshield wipers. “You don’t know exactly when you’re going to crash, or whether the loss of this or that function is going to tip you into crashing,” he said. “But crash seems imminent.”

The only flaw in Worm’s analogy is that oceanic crash isn’t imminent. There’s still time to fix things, his work shows. But time is running out.