The United States is on the brink of its most consequential transformation since the New Deal. Read more about what it takes to decarbonize the economy, and what stands in the way, here. This story was originally published by YaleE360 and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

In Odessa, Texas, workers at a startup called SolarCycle unload trucks carrying end-of-life photovoltaic panels freshly picked from commercial solar farms across the United States. They separate the panels from the aluminum frames and electrical boxes, then feed them into machines that detach their glass from the laminated materials that have helped generate electricity from sunlight for about a quarter of a century.

Next, the panels are ground, shredded, and subjected to a patented process that extracts the valuable materials—mostly silver, copper, and crystalline silicon. Those components will be sold, as will the lower-value aluminum and glass, which may even end up in the next generation of solar panels.

This process offers a glimpse of what could happen to an expected surge of retired solar panels that will stream from an industry that represents the fastest-growing source of energy in the US. Today, roughly 90 percent of panels in the US that have lost their efficiency due to age, or that are defective, end up in landfills because that option costs a fraction of recycling them.

But recycling advocates in the US say increased reuse of valuable materials, like silver and copper, would help boost the circular economy, in which waste and pollution are reduced by constantly reusing materials. According to a 2021 report by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), recycling PV panels could also cut the risk of landfills leaking toxins into the environment; increase the stability of a supply chain that is largely dependent on imports from Southeast Asia; lower the cost of raw materials to solar and other types of manufacturers; and expand market opportunities for US recyclers.

Of course, reusing degraded but still-functional panels is an even better option. Millions of these panels now end up in developing nations, while others are reused closer to home. For example, SolarCycle is building a power plant for its Texas factory that will use refurbished modules.

The prospect of a future glut of expired panels is prompting efforts by a handful of solar recyclers to address a mismatch between the current buildup of renewable energy capacity by utilities, cities, and private companies—millions of panels are installed globally every year—and a shortage of facilities that can handle this material safely when it reaches the end of its useful life, in about 25 to 30 years.

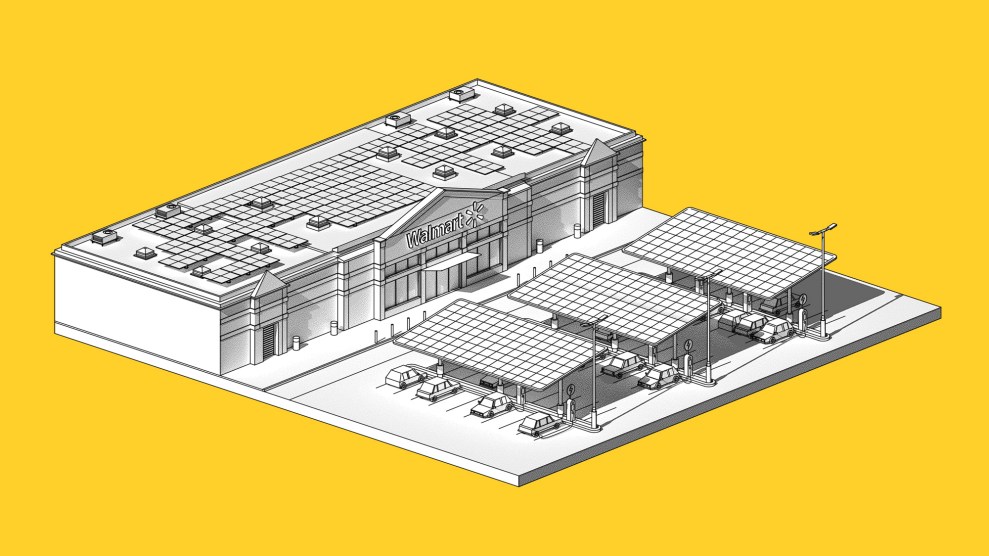

Solar capacity across all segments in the US is expected to rise by an average of 21 percent a year from 2023 to 2027, according to the latest quarterly report from the Solar Energy Industries Association and the consulting firm Wood Mackenzie. The expected increase will be helped by the landmark Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 which, among other supports for renewable energy, will provide a 30 percent tax credit for residential solar installations.

The area covered by solar panels that were installed in the US as of 2021 and are due to retire by 2030 would cover about 3,000 American football fields, according to an NREL estimate. “It’s a good bit of waste,” said Taylor Curtis, a legal and regulatory analyst at the lab. But the industry’s recycling rate, at less than 10 percent, lags far behind the upbeat forecasts for the industry’s growth.

Jesse Simons, a co-founder of SolarCycle, which employs about 30 people and began operations last December, said solid waste landfills typically charge $1 to $2 to accept a solar panel, rising to around $5 if the material is deemed hazardous waste. By contrast, his company charges $18 per panel. Clients are willing to pay that rate because they may be unable to find a landfill licensed to accept hazardous waste and assume legal liability for it, and because they want to minimize the environmental impact of their old panels, said Simons, a former Sierra Club executive.

SolarCycle provides its clients with an environmental analysis that shows the benefits of panel recycling. For example, recycling aluminum uses 95 percent less energy than making virgin aluminum, which bears the costs of mining the raw material, bauxite, and then transporting and refining it.

The company estimates that recycling each panel avoids the emissions of 97 pounds of CO2; the figure rises to more than 1.5 tons of CO2 if a panel is reused. Under a proposed Securities and Exchange Commission rule, publicly held companies will be required to disclose climate-related risks that are likely to have a material impact on their business, including their greenhouse gas emissions.

Stripped from solar panels at the SolarCycle plant, aluminum is sold at a nearby metal yard. Glass is currently sold for just a few cents per panel for reuse in basic products like bottles, but Simons hopes he will eventually have enough of it to sell for a higher price to a manufacturer of new solar panel sheets.

Crystalline silicon, used as a base material in solar cells, is also worth recovering, he said. Although it must be refined for use in future panels, its use avoids the environmental impacts of mining and processing new silicon.

SolarCycle is one of only five companies in the US listed by the SEIA as capable of providing recycling services. The industry remains in its infancy and is still figuring out how to make money from recovering and then selling panel components, according to the US Environmental Protection Agency. “Elements of this recycling process can be found in the United States, but it is not yet happening on a large scale,“ the EPA said in an overview of the industry.

In 2016, the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) forecast that by the early 2030s, the global quantity of decommissioned PV panels will equal some 4 percent of the number of installed panels. By the 2050s, the volume of solar panel waste will rise to at least 5 million metric tons a year, the agency said. China, the world’s biggest producer of solar energy, is expected to have retired a cumulative total of at least 13.5 million metric tons of panels by 2050, by far the largest quantity among major solar-producing nations and nearly twice the volume the US will retire by that time, according to the IRENA report.

The raw materials technically recoverable from PV panels globally could cumulatively be worth $450 million (in 2016 terms) by 2030, the report found, about equal to the cost of raw materials needed to produce some 60 million new panels, or 18 gigawatts of power-generation capacity. By 2050, the report said, recoverable value could cumulatively exceed $15 billion.

For now, though, solar recyclers face significant economic, technological, and regulatory challenges. Part of the problem, says NREL’s Curtis, is a lack of data on panel recycling rates, which hinders potential policy responses that might provide more incentives for solar-farm operators to recycle end-of-life panels rather than dump them.

Another problem is that the Toxicity Characteristic Leaching Procedure—an EPA-approved method used to determine whether a product or material contains hazardous elements that could leach into the environment—is known to be faulty. Consequently, some solar farm owners end up “over-managing” their panels as hazardous without making a formal hazardous-waste determination, Curtis said. They end up paying more to dispose of them in landfills permitted to handle hazardous waste or to recycle them.

The International Energy Agency assessed whether solar panels that contain lead, cadmium, and selenium would impact human health if dumped in either hazardous-waste or municipal landfills and determined the risk was low. Still, the agency said in a 2020 report, its findings did not constitute an endorsement of landfilling: Recycling, it stated, would “further mitigate” environmental concerns.

NREL is currently studying an alternative process for determining whether or not panels are hazardous. “We need to figure that out because it is definitely impacting the liability and the cost to make recycling more competitive,” Curtis said.

Despite these uncertainties, four states recently enacted laws addressing PV module recycling. California, which has the most solar installations, allows panels to be dumped in landfills, but only after they have been verified as non-hazardous by a designated laboratory, which can cost upwards of $1,500. As of July 2022, California had only one recycling plant that accepted solar panels.

In Washington state, a law designed to provide an environmentally sound way to recycle PV panels is due to be implemented in July of 2025; New Jersey officials expect to issue a report on managing PV waste this spring; and North Carolina has directed state environmental officials to study the decommissioning of utility scale solar projects. (North Carolina currently requires solar panels to be disposed of as hazardous waste if they contain heavy metals like silver or—in the case of older panels—hexavalent chromium, lead, cadmium, and arsenic.)

In the European Union, end-of-life photovoltaic panels have, since 2012, been treated as electronic waste under the EU’s waste electrical and electronic equipment directive, known as WEEE. The directive requires all member states to comply with minimum standards, but the actual rate of e-waste recycling varies from nation to nation, said Marius Mordal Bakke, senior analyst for solar supplier research at Rystad Energy, a research firm headquartered in Oslo, Norway. Despite this law, the EU’s PV recycling rate is no better than the US rate—around 10 percent—largely because of the difficulty of extracting valuable materials from panels, Bakke said. “It will become profitable by itself regardless of commodity prices.”