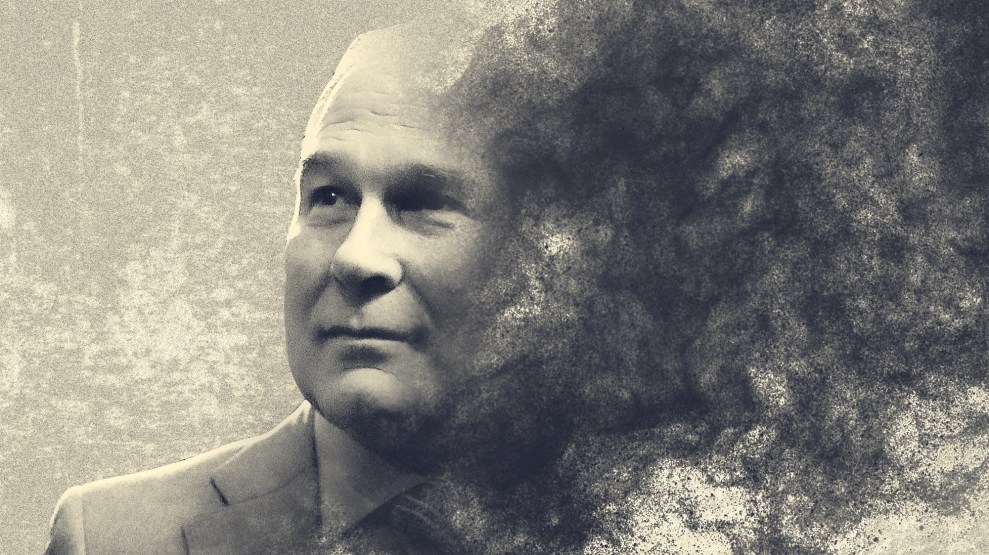

Gage Skidmore/Flickr

This story was originally published by The New Republic and appears here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Pope Francis sparked a media frenzy in 2015 with the release of his second encyclical, Laudato Si. One of the highest forms of official Catholic Church teaching, the document presented the moral case for tackling climate change on behalf of the poor and vulnerable. But there was another, less-noticed purpose for Francis’s document: To reject an insidious notion among Christians that God wants humans to exploit the Earth’s natural resources.

This notion stems from the book of Genesis, in which God gives man “dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creeps on the earth.” Some Christians wrongly believe that this passage “invites us to subjugate the earth, the savage exploitation of nature would be encouraged, presenting the image of human beings as ruler and destroyer,” Francis wrote. “This is not the correct interpretation of the Bible as intended by the Church.”

The idea that “dominion” is a free pass to exploit is nonetheless central to Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Scott Pruitt, who has recently become the de facto spokesperson for the anti-Pope brand of Christian environmentalism. Speaking on the pro-Trump Christian Broadcasting Network last week, Pruitt said his faith is partially what motivates him to remove regulations on higher-polluting sources of energy like coal, oil, and natural gas. “The biblical worldview with respect to these issues is that we have a responsibility to manage and cultivate, harvest the natural resources that we’ve been blessed with to truly bless our fellow mankind,” he said. Those comments attracted a lot of media attention, but it’s not the first time he has invoked his faith to defend his policies. “God has blessed us with natural resources,” he told Politico in July. “Let’s use them to feed the world. Let’s use them to power the world. Let’s use them to protect the world.”

Pruitt’s rejection of Pope Francis isn’t exactly scandalous—he’s a Southern Baptist, not a Catholic. Nick Garland, a senior pastor at the church Pruitt attended in Oklahoma, told E&E News that his congregation is in favor of using natural resources. “In Genesis, he [God] put man in it to have dominion; he says [man] should work over it,” he said. “Those are the mandates that he set not just for Adam but mankind.” The Southern Baptist Convention also published a resolution in 2007 casting doubt on the science of global warming and declaring that Christians should exercise dominion over the Earth.

But even within Pruitt’s denomination, this interpretation of “dominion” has been controversial. The year after the 2007 resolution, several prominent leaders of the Southern Baptist Convention rejected it, saying humans “must be proactive and take responsibility” for climate change. One of the most prominent, almost pope-like Southern Baptist leaders, the recently deceased Billy Graham, also wrote that men should use the Earth’s resources “wisely, instead of poisoning or destroying it.”

We don’t worship the earth; instead, we realize that God gave it to us, and we are accountable to Him for how we use it. After creating Adam, the first man, the Bible says, “The Lord God took the man and put him in the Garden of Eden to work it and take care of it” (Genesis 2:15). God didn’t tell him to exploit the world or treat it recklessly, but to watch over it and use it wisely. Like a good ruler, we should seek the welfare of everything God entrusts to us—including the creation. The Bible says, “A righteous man cares for the needs of his animal” (Proverbs 12:10).

The interpretation of “dominion” is not up for debate in most parts of the world, Reverend Dave Bookless, the director of theology at the Christian conservation group A Rocha International, said. “Really, the majority view amongst academic theologians, and most bible scholars, is in line with what the Pope has said,” Bookless added. “I would struggle to find, certainly in Europe and most parts of the world, a recognized theologian who would take the kind of view Pruitt is taking now.”

The debate over whether God wants humans to exploit the Earth’s resources really only came into prominence slightly before the industrial revolution, when humans began spewing more pollution into the environment, Bookless said. “The growth of this view into prominence happens simultaneously with the overexploitation of the Earth’s resources,” he said. “There was this convenient theology to justify it that said, God has given us dominion, and dominion equals domination, therefore the Earth is for us, and we can do what we like with it.”

Pruitt’s interpretation of “dominion” is certainly convenient, given his close ties to industry players and the regulations he has loosened at their request. Rules to clean up coal plants and coal waste, fuel-efficiency rules for cars and trucks, rules to prevent methane leaks from oil and gas—all are on their way out, at Pruitt’s doing. Is that because he has held, according to The New York Times, “back-to-back meetings, briefing sessions and speaking engagements almost daily with top corporate executives and lobbyists from all the major economic sectors that he regulates,” or is it because of his evangelicalism?

If it is because of his faith, it’s a faith that’s on the fringes of theology, said Jame Schaefer, a professor of systematic theology at Marquette University. “Pruitt’s interpretation [of ‘dominion’] is not ‘theological’ per se—not a reflection based on biblical scholars’ findings that result from using exegetical methods of interpretation to try to come as close as possible to the meaning intended when written,” she wrote in an email. “Unfortunately, he seems to miss the major point: ‘The earth is the Lord’s as the Psalmists rejoice!’ Earth is not Pruitt’s, any leader’s, or any nation’s for use that degrades, destroys, uses up, or precludes use by others for their necessities of life.”

While Pruitt’s conflation of “dominion” and “domination” may not be theologically correct, Bookless said, his interpretation is certainly politically savvy. “It will appeal to people who have lost their jobs in industry and want them back,” he said. “The narrative will play to Trump’s supporters, but it’s not a view that’s mainstream Christian theology at all.”