Chinese President Xi Jinping welcomes President Barack Obama in Beijing.Liu Jiansheng/Xinhua/ZUMA

On Tuesday, China and the United States announced an unprecedented plan to work together to fight global warming. The deal includes new trade partnerships and significant new greenhouse gas goals for both countries. The US pledged to cut its emissions by up to 28 percent by 2025, while China agreed that its emissions would peak around 2030 and promised to get one-fifth of its power from non-fossil-fuel energy sources by the same year. Environmental groups have roundly welcomed the plan as an important step. But critics of the deal—including congressional Republicans—say China has been let off lightly and that it won’t follow through with its commitments.

The reality, of course, is far more complex. So I asked experts on US-China relations to explain why this deal was so attractive to the leaders of two countries that have historically locked horns over everything from human rights to lingerie imports. Here’s their explanation of why China really does want to want to act on climate change, and why the bargain makes sense for President Barack Obama, as well:

China has to act on air pollution. If it doesn’t, the country risks political instability. Top Republicans have slammed the US-China deal as ineffective and one-sided. “China won’t have to reduce anything,” complained Sen. Jim Inhofe (Okla.) in a statement, adding that China’s promises were “hollow and not believable.”

But the assumption that China won’t try to live up to its end of the bargain misses the powerful domestic and global incentives for China to take action. The first, and most pressing, is visible in China’s appalling air quality. President Xi Jinping needs to act now, says Jerome A. Cohen, a leading Chinese law expert at New York University. Why? Because “the environment—not only the climate—is the most serious domestic challenge he confronts.” And Xi has the power to follow through on this “ambitious and necessary commitment,” says Cohen, who notes that the Chinese president will likely be in charge for eight more years and has “no overt opposition to his impressive power.”

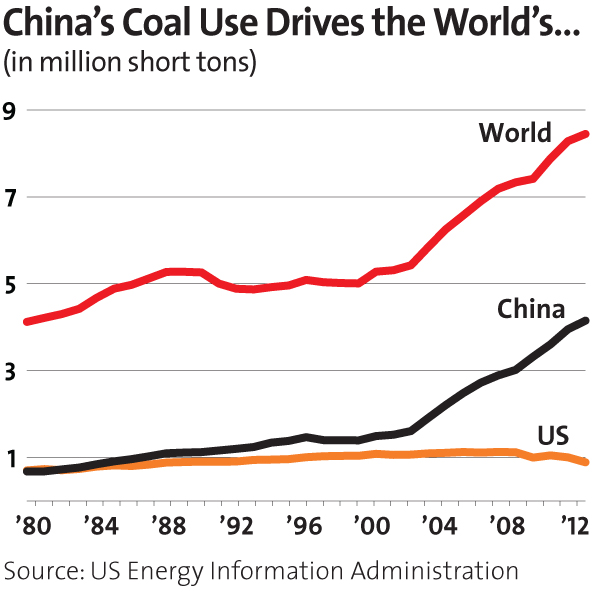

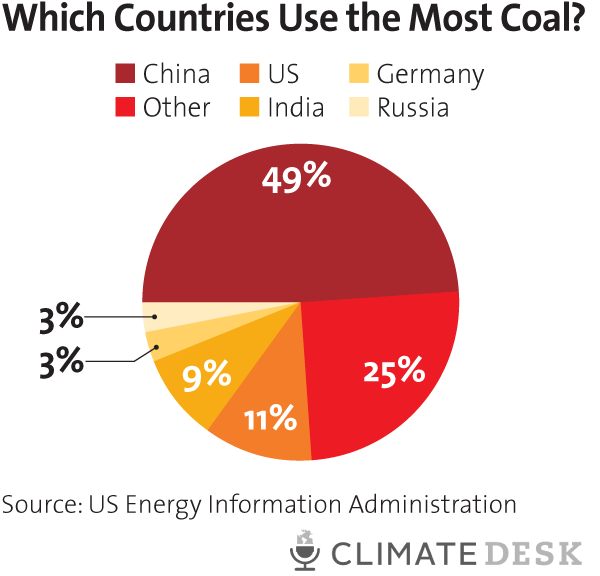

Over the past few decades, China has witnessed the fastest and deepest wealth creation in history, hauling millions out of poverty in the space a generation. That growth has been heavily reliant on coal, which makes up roughly 70 percent of the country’s total energy consumption. China is the world’s top coal consumer and producer. All that has come with big cost: toxic air. According to one Lancet study, pollution generated mostly by cars and the country’s 3,000 coal-fired power plants killed 1.2 million Chinese people in 2010.

That’s why, Cohen says, this new announcement is such a big win for Chinese people themselves—it’s a clear demonstration that the country’s leaders are confronting China’s largest crisis. “This is very encouraging progress on a crucial issue of human rights: the right to a nonthreatening environment,” he says.

China’s air has become a major political threat to the Communist Party. As we reported in our yearlong investigation into China’s fracking plans, the country has a daily average of 270 “mass incidents”—unofficial gatherings of 100 or more demonstrators—sparked in part by pollution and environmental degradation. The message is clear. As The New Yorker‘s Evan Osnos put it, if the government doesn’t figure out a way to respond, “then it’s a political crisis, not just an environment crisis.” That’s what my colleague Jaeah Lee and I found when we toured China last year: It’s impossible to escape the scourge of coal. To understand why China wants to act now, you need to understand just how desperate the crisis has become:

The Atlantic‘s James Fallows made this point Wednesday, writing that “when children are developing lung cancer, when people in the capital city are on average dying five years too early because of air pollution, when water and agricultural soil and food supplies are increasingly poisoned, a system just won’t last.”

You can watch Fallows explain just how closely tied China’s environmental crisis is to the fortunes of the Communist Party:

President Xi Jinping wants to be a powerful global player. Another motivation for Chinese action has to do with global politics, says Orville Schell, who directs the Center on US-China Relations at the Asia Society in New York.

“Xi Jinping is a very tough, muscular, nationalist leader whose toolbox is taken from earlier Mao periods,” Schell said in a phone interview. According to Schell, Xi’s preference for assertive leadership on the world stage means that China is “going to accept much less hectoring and bullying” from the rest of the world, perceived or otherwise. “They are going to be much more defiant.”

This deal—in which China is appearing on the world stage as an equal partner with the United States—fits into that narrative, explains NYU’s Cohen. The “climate issue is needed to boost sagging and increasingly tense Sino-American relations,” he said. “Xi is pursuing a two-faced policy toward the US: progress on issues of critical importance to him and his party/state, and relentless hostility toward the continuing soft power influence of the US over the Chinese people and China’s neighbors. Xi is facing severe internal challenges. He sees that the US can help him on some and undermine him on others, so, following one of Chairman Mao’s famous maxims, he is ‘walking on two legs.'”

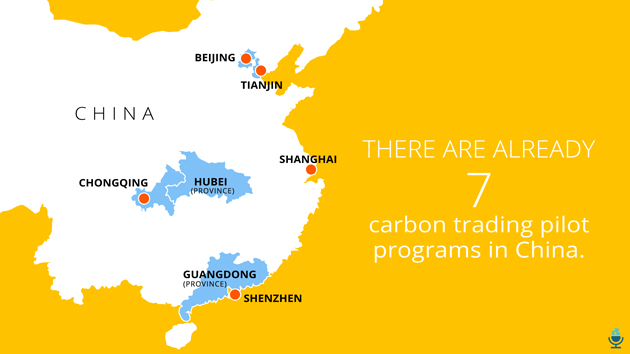

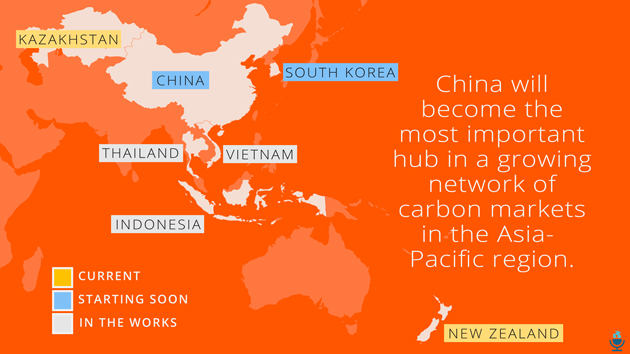

China is actually serious about climate change. It’s not the case that everything is about the machinery of global politics—or even simply about China’s domestic worries over air quality. China’s recent actions suggest that its policymakers are actually attempting to confront global warming. Beijing has committed to gradually shut down coal plants inside the city by 2017. Obama and Xi agreed last year to curb the use of hydrofluorocarbons—powerful greenhouse gases that are used in refrigerants. In September, China announced it was moving forward with plans for a massive, nationwide cap-and-trade program intended to help combat climate change. The program will launch in 2016, but there are already a series of pilot carbon markets across the country.

So what does Obama get out of this deal? Despite Republican criticisms that the deal lets China off the hook, Schell says that Obama gets to own a big foreign policy success—one that actually helps him achieve a major domestic policy goal. Obama’s success with China was born out of failure at home: “He’s had to export his hopes and dreams for some sort of collaborative solution in China,” Schell said. “China, paradoxically, has allowed Obama to say that he has followed through with his earlier commitments to take climate change seriously.”

Cohen warns that opposition to climate action in the US could still undermine the bilateral agreement, but he says he’s hopeful that Obama “can implement the US commitment.”

As for whether the deal could signal a larger breakthrough by the Obama administration in US-China relations, the experts are skeptical. “The two big moments—the breakthrough moments—in US-China relations, were Nixon in ’72 and Carter recognizing China when Deng Xiaoping came to the US in ’79,” says Schell. “This is not the case this time with Obama in China.” Still, Schell says that any agreement with the tough Chinese leadership “does represent some progress.”

After all, he says, Obama “certainly can’t do anything at home.”