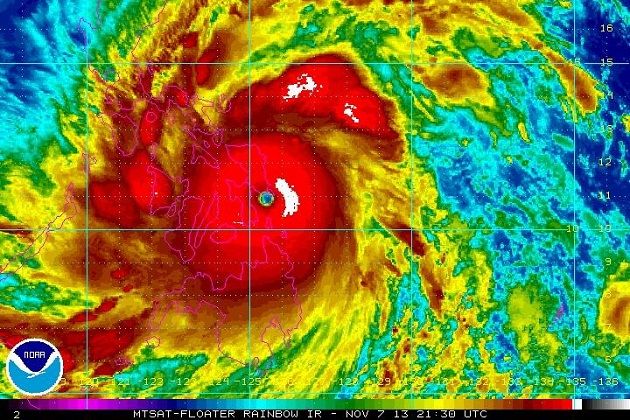

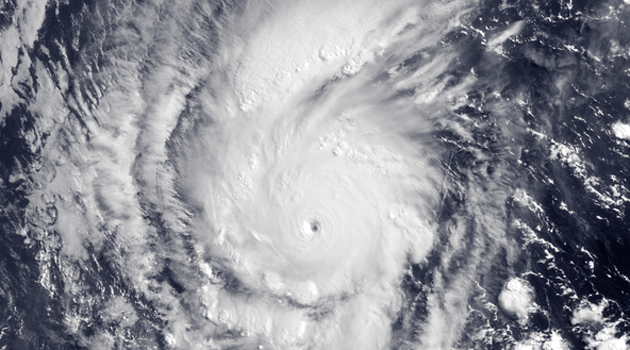

Hurricane Amanda in the eastern Pacific on May 25<a href="http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Amanda_May_25_2014_1445Z.png">NOAA</a>/Wikimedia Commons

Usually, people living in the United States don’t pay much attention to hurricanes in the eastern Pacific, the other basin where megastorms that can affect North America are formed. Mostly, these storms wallop Mexico, or travel harmlessly out to sea. So, given the standard myopia of the media, we rarely hear much about them.

But this year, perhaps, we ought to be paying more attention. The eastern Pacific hurricane season started on May 15, and already, with its first storm, it has set an ominous record. The hurricane in question, named Amanda, spun up south of the Baja California peninsula Thursday, and on Sunday it attained maximum sustained wind speeds of 155 miles per hour—just below Category 5 status. Or as National Hurricane Center forecaster Stacy Stewart put it when the storm reached its peak strength: “Amanda is now the strongest May hurricane on record in the eastern Pacific basin during the satellite era.”

This record is notable for two reasons. First of all, even though there remains a great deal of uncertainty and debate about the relationship between hurricanes and global warming, the fact is that in many hurricane basins across the world, new storm intensity records have been set just since the year 2000. Amanda therefore fits into this broader pattern.

Second, there is growing evidence that El Niño conditions—characterized by an eastward shift of warm water across the great Pacific Ocean, with global weather ramifications—are developing in the Pacific right now. The latest forecast from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration now gives us a greater than 65 percent chance that El Niño conditions will develop by this summer.

In El Niño years, we tend to see a great firing of hurricane activity in the eastern Pacific, and a suppression of these storms in the Atlantic. In fact, the strongest storm ever recorded in the eastern Pacific, Category 5 Hurricane Linda in 1997, occurred during the last super-strong El Niño year.

So if El Nino does occur, Amanda may not be the strongest storm that we see in the Eastern Pacific this year. That’s potentially bad news for Mexico. In fact, there is even a tiny possibility that during an El Niño year, a storm might be able to travel as far north as Southern California (albeit in a pretty weakened state), as Hurricane Linda was at one point forecast to do. In fact, recent historical work on past hurricanes has revealed that in 1858, San Diego was struck by what appears to have been a Category 1 hurricane.

As of now, Hurricane Amanda has weakened and is not expected to affect land in a serious way. But this is definitely a storm whose significance extends well beyond its immediate impact.