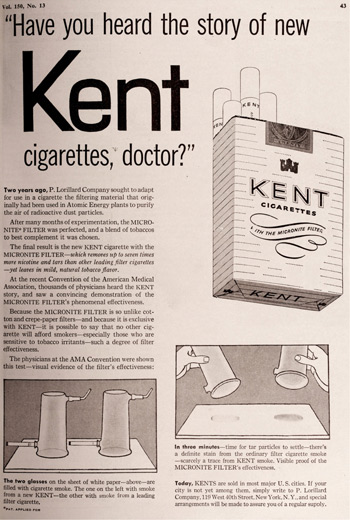

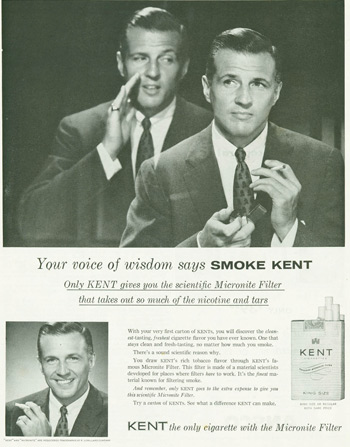

From a 1950s ad: "Only KENT gives you the scientific Micronite filter that takes out so much of the nicotine and tars."

It’s hard to think of anything more reckless than adding a deadly carcinogen to a product that already causes cancer—and then bragging about the health benefits. Yet that’s precisely what Lorillard Tobacco did 60 years ago when it introduced Kent cigarettes, whose patented ‘Micronite” filter contained a particularly virulent form of asbestos.

Smokers puffed their way through 13 billion Kents between March 1952 and May 1956, when Lorillard changed the filter design. Six decades later, the legal fallout continues—just last month, a Florida jury awarded more than $3.5 million in damages to a former Kent smoker stricken with mesothelioma, an extremely rare and deadly asbestos-related cancer that typically shows up decades after the initial exposures.

Lorillard and Hollingsworth & Vose, the company that supplied the asbestos filter material, face numerous claims from mesothelioma sufferers, both factory workers who produced the cigarettes or filter material and former smokers who say they inhaled the microscopic fibers. (The companies insist that hardly any fibers escaped.) There’s been a burst of new lawsuits in the last few years, according to SEC filings, possibly because a mesothelioma patient these days is almost certain to be asked by his doctor or lawyer, “Did you happen to smoke Kents in the 1950s?”

While there’s no official count, records and interviews suggest that mesothelioma claims since the 1980s number in the low hundreds at least. Lorillard’s filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission show that it settled 90 cases during a recent period of just over two years, and that another 60 are still pending. Lorillard officials did not reply to emails and calls for this story, and H&V declined interview requests—company lawyer Andrew McElaney did, however, point out that the companies have won most of the cases that went to trial.

Lorillard, based in Greensboro, NC, is America’s third-leading cigarette maker, with a market share of nearly 15 percent and 2012 sales exceeding $6.6 billion. Established in 1760 as the P. Lorillard Co., it is one of the nation’s oldest continuously operated companies. It also owns the electronic cigarette-maker blu eCigs, which recently created a buzz with commercials featuring TV personality Jenny McCarthy and actor Stephen Dorff.

Kent was Lorillard’s response to the health scare of the early 1950s, when the link between smoking and lung cancer began drawing wide attention. Tobacco companies scurried to roll out filters to calm jittery smokers and keep them from quitting in droves. The health benefits would prove illusory, but the switch to filters averted the potential loss of millions of customers. “The industry’s own researchers admitted that filters did nothing to make cigarettes safer,” notes Robert Proctor, a Stanford University historian whose 2012 book, Golden Holocaust, covers Big Tobacco’s tactics in painstaking detail. “Philip Morris scientists in 1963 admitted that ‘the illusion of filtration’ was as important as ‘the fact of filtration.'”

Lorillard named its first filtered cigarette for Herbert A. Kent, briefly its president, and aggressively touted the superiority of the Micronite filter, a blend of cotton, acetate, crepe paper, and crocidolite asbestos—sometimes called “African” or “Bolivian blue” asbestos because of its bluish tint.

The risk of deadly lung disease for heavily exposed asbestos miners and plant workers was already well documented, but asbestos also was known as an effective filter material, dense enough to stop minute particles and gases. Lorillard learned of the use of crocidolite in gas masks made for the Army Chemical Corps. Under its contract with H&V, Lorillard assumed sole responsibility for any “harmful effects.” It launched Kent at a press conference at New York’s Waldorf-Astoria, touting the Micronite filter as “the greatest health protection in cigarette history.”

Playing on the public’s gee-whiz faith in science and technology, Kent ads told a glamorous, if vague, back story of how the quest for a new filter “ended in an atomic energy plant, where the makers of KENT found a material being used to filter air of microscopic impurities.”

“What is ‘Micronite’?” another ad asked. “It’s a pure, dust-free, completely harmless material that is so safe, so effective, it actually is used to help filter the air in operating rooms of leading hospitals.”

The marketing blitz included ads in medical journals and Kent gift boxes for physicians, accompanied by “Dear Doctor” letters talking up the advantages for “patients whom you have felt obliged to advise to cut down or cut out smoking.”

The filter material was produced at H&V plants in Massachusetts and shipped to Lorillard plants in Kentucky and New Jersey. For H&V workers, the results were catastrophic: One woman, Elizabeth Jacobs, buried her husband and brother, both H&V workers, who died of mesothelioma and asbestosis, respectively. Jacobs herself would die of mesothelioma at age 54. Her only known exposure to asbestos came from laundering her husband’s dusty work clothes.

The plant was a “dust-creating monster,” James A. Talcott, an oncologist who coauthored a study of H&V filter workers, told me. Published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1989, Talcott’s study tracked the health status of 33 former employees of the company’s West Groton plant. By the time the paper came out, 28 of them had died—more than triple the expected number based on life expectancies—18 of them from asbestos-related illnesses. Four of the five surviving workers had been stricken as well. Dozens of Lorillard workers also died of mesothelioma—an exhibit in a Louisville court case listed 34 victims by their initials.

While plant workers clearly were exposed, how much asbestos Kent smokers inhaled has been a far more contentious subject. Internal documents highlight Lorillard’s anxieties that its customers were breathing asbestos. An April 1954 letter from Lorillard’s research director to the company president states that researchers had found “traces of mineral fiber” in the smoke: “We are embarked upon a program of attempting to work out a method for the elimination of the presence of such fibers.” That September, an H&V official sent a memo discussing the need “to find a way of anchoring asbestos…All efforts are to be exerted to solve the asbestos-dust-in-Kent smoke problem.”

In another memo two months later, H&V’s president stated: “It is Lorillard’s belief that asbestos must be eliminated from the Kent cigarette as soon as possible because of a whispering campaign started by their competitors of the harmful effects of asbestos.” As a result, H&V would “discontinue that part of our research program devoted to the fixing of asbestos fibres and direct the entire attention of the program toward the complete elimination of asbestos.”

Lorillard nevertheless continued using asbestos in its filters for another 16 months, and sold existing stocks of Kents for several more.

The filter litigation is hardly Lorillard’s biggest challenge. It depends on its popular Newport menthol brand for nearly 90 percent of sales, and the Food and Drug Administration is considering whether to restrict the use of menthol in cigarettes.

Lorillard also faces some 4,500 lawsuits by individual smokers in Florida, thanks to a state Supreme Court ruling that made it easier to sue for smoking-related harms. Yet whil the filter lawsuits are but a small fraction of that, Lorillard fights them fiercely. “They litigate hard,” says Timothy F. Pearce, a lawyer with Levin Simes in San Francisco who tried a filter case in 2011, and won. “It’s no small undertaking to be in a trial with them,” he says. “They had like 13 lawyers” working the case.

Lorillard and H&V have won 17 of the 23 filter cases that went to trial. They insist in court that little or no asbestos leaked from Kent filters, and so plaintiffs must have gotten mesothelioma in some other way. Despite the nervous tone of the internal letters and memos, they say that tests of Kent smoke in the early ’50s never found more than three fibers per cigarette. The smokers’ exposures were “very, very low,” Kevin H Reinert, Lorillard’s director of regulatory science policy, testified in a deposition in April. “I don’t believe it increased the risk.” Plaintiffs have found this hard to challenge, since Lorillard failed to preserve most of its original test reports.

Plaintiff experts who tested cigarettes from old packs of Kents have found abundant asbestos fibers in the smoke. Lorillard and H&V claim that the tests were unreliable because the cigarettes have deteriorated with age.

The companies’ first line of defense, though, has been to convince juries that plaintiffs didn’t smoke Kents in the first place—they just say they did because they have a bad memory, or maybe they are shading the truth. To undermine their credibility, defense lawyers and investigators fan out around the country to track down and interview family members, school chums, Army buddies—anyone who might have known the plaintiff in the 1950s.

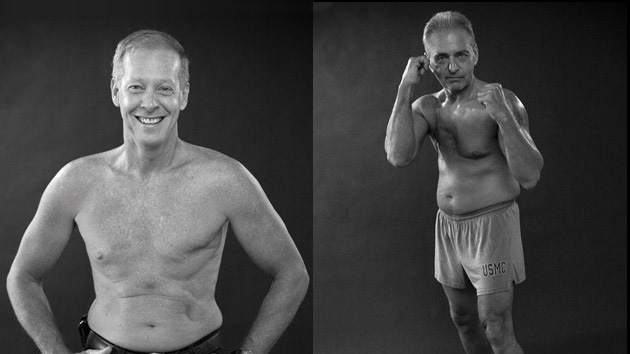

Because it can be hard to establish the brand of cigarette a person smoked decades ago, the strategy often succeeds. It failed, however, in the case of 76-year-old Don Lenney, who not only won in court, but is still alive nearly four years after his diagnosis. (Mesothelioma victims often die within a year.)

Lenney, a former insurance agent in Northern California, says he started smoking in high school, and soon switched from unfiltered brands: “The Kent Micronite filter was supposed to be the healthy alternative, so I started smoking Kents.”

Diagnosed with mesothelioma in November 2009, Lenney had his left lung removed and underwent chemotherapy and radiation treatments. He also sued Lorillard and H&V. “They attacked my credibility as far as whether I had actually smoked Kent cigarettes,” Lenney recalls. Their investigators “were very pushy,” he adds. “They would knock on somebody’s door and just ask to interview them…without even calling first to set up an appointment.”

In March, 2011, a state jury in San Francisco found Lorillard and H&V liable. The judge later ordered them to pay Lenney and his wife about $1.1 million in damages and costs. The companies appealed, and the case was settled out of court.

Dimitris O. Couscouris, a Los Angeles-area resident with mesothelioma, did not fare as well. Lorillard mounted a relentless attack on his credibility, suggesting that he had evaded the draft during his teenage years in Australia, and had once improperly received unemployment benefits.

Defense lawyers also seized on a statement by a witness who said Couscouris had become too sick to walk. They sent a private investigator to spy on Couscouris at home—the private eye videotaped him and his wife getting into their car and making a few stops, including at a Marie Callendar restaurant and a shopping mall.

In October, 2012, a Los Angeles jury found that Couscouris had failed to prove he’d smoked Kents. “The trial ended up being more of an attack on my client,” says Trey Jones, Couscouris’ lawyer. “Almost like a ‘blame the victim’ type thing.”

FairWarning.org is a Los Angeles-based nonprofit investigative news organization focused on public health and safety issues.