Sheep relax in their "lambie jammies" at the Contra Costa County Fair. Photos by Kiera Butler

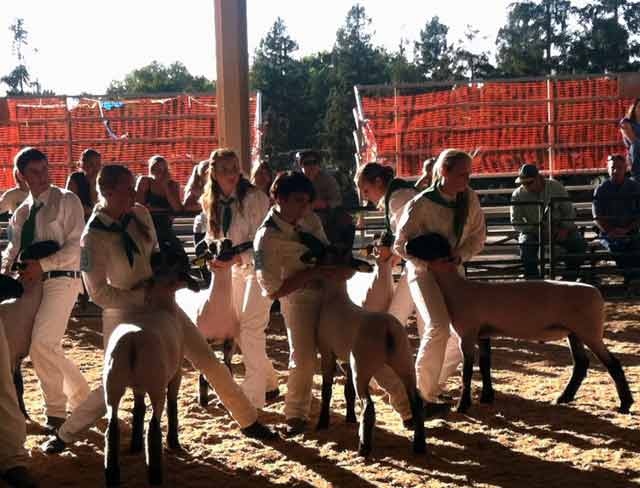

Over the past few weeks, I’ve logged an awful lot of hours at county fairs. What, you might ask, is the draw? It’s not the rides, deep fried watermelon on a stick, or omnipresent hot-tub sales. Don’t get me wrong, I like all that stuff. (Well, some of it, anyway.) But the main purpose of my visits has been a reporting project about youth livestock competitions. At most county fairs, you’ll find the livestock pavilion at the fringes of the fair, a world away from the crowds of the midway. Most of the competitors, who range in age from 9-19, are members of 4-H club or Future Farmers of America (FFA). Dressed in white uniforms and boots, these kids are easy to pick out of a crowd. Almost across the board, the kids I talked to were friendly, poised, and eager to tell me all about what they do. A few things I picked up during my visits:

1. It’s not just rural kids that raise livestock.

Around here, kids from cities and suburbs are a major force at the fair. While some of them have enough space and resources to raise their animals at home, others keep their livestock at friends’ or neighbors’ homes. 4-H club also offers a few community spaces to kids—for example, some members of 4-H in suburban Pleasant Hill, California, raise pigs, goats, and sheep at Borges Ranch, a facility managed by the neighboring city of Walnut Creek, California. Below is Allison, a 16-year-old Pleasant Hill 4-Her holding one of the baby pygmy goats that her club keeps at Borges. Pleasant Hill 4-H brought its goats to the Contra Costa County Fair in Antioch, California, a few weeks ago.

One of the clubs that brought animals to the Alameda County Fair is Montclair 4-H, based in the city of Oakland, California:

2. You can compete in just about anything at the county fair.

In the small animals barn at the Alameda County Fair, teams of 4-H kids compete in rabbit bowl and avian bowl, quiz-show-style contests wherein participants answer questions about anatomy, diseases, breeds, and other trivia about rabbits and chickens. Unfortunately I missed something called the Call Your Chicken Contest. Over in the Food and Fiber Arts pavilion I enjoyed the entries in what seemed to be a contest for sock monkeys dressed as characters from children’s books.

In the small animals barn at the Alameda County Fair, teams of 4-H kids compete in rabbit bowl and avian bowl, quiz-show-style contests wherein participants answer questions about anatomy, diseases, breeds, and other trivia about rabbits and chickens. Unfortunately I missed something called the Call Your Chicken Contest. Over in the Food and Fiber Arts pavilion I enjoyed the entries in what seemed to be a contest for sock monkeys dressed as characters from children’s books.

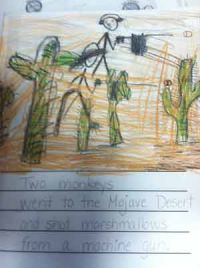

My favorite nonlivestock contest, though, was poetry in the kindergarten division. A particularly fine specimen is to your left. (In case you’re having trouble reading the text, which appears to have been faithfully transcribed in pencil by a parent or teacher, it reads: “Two monkeys/went to the Mojave Desert/and shot marshmallows/from a machine gun.” Right on, man.)

3. There’s such thing as lambie jammies.

These attractive jumpsuits keep your sheep clean, and they seem to come in every color and pattern imaginable. In addition to the styles shown below, I saw skull and crossbones, camo, and pink camo lambie jammies at the fairs. Rumor has it that you can also buy a human headband in the same material as your sheep’s jammies, so you can, you know, match.

4. It’s not just the animal that gets judged at the county fair—it’s the kid, too.

When I visited the Alameda County Fair last year, I had only the vaguest idea of what might be required of a kid raising a show animal. Food, water, maybe the occasional stall cleaning—how hard could it be? Pretty damn hard, it turns out. This year, I kept tabs on a few kids as they prepared for fair. In addition to feeding and cleaning, kids have to train their animals to behave in the ring. The process is different for each species, but it’s always a huge time commitment—sometimes as much as two or three hours a day.

This is Kelly, a 16-year-old 4-Her from Castro Valley, California, working with one of her lambs a few months ago. She’s teaching the lamb to lean up against her leg, flexing its back. This position, called a “brace,” helps the judge see the lamb’s balance of muscle and fat.

All this preparation counts in the ring, since competitors who have practiced a lot can emphasize their animals’ good qualities and downplay the bad. But it’s especially important in the “showmanship” portion of the competition, when the judge evaluates the competitor’s skills rather than the animal’s body. The winner of the showmanship contest in each species moves on to “master showmanship,” where each winner must show each species.

All this preparation counts in the ring, since competitors who have practiced a lot can emphasize their animals’ good qualities and downplay the bad. But it’s especially important in the “showmanship” portion of the competition, when the judge evaluates the competitor’s skills rather than the animal’s body. The winner of the showmanship contest in each species moves on to “master showmanship,” where each winner must show each species.

Showmanship competitions are divided into classes by age, with the youngest kids at the beginning and the oldest at the end. The kids cluster around the show ring to watch the judge and try to figure out what he’s looking for in a showman. This can vary widely from judge to judge; the sheep judge at the Alameda show, for example, favored an extremely low stance. “He practically wants us to do squats,” I overheard one sheep shower groan as she watched.

Here, members of the master showmanship class show off their brace with market goats:

Of all the showmanship contests I saw, senior master sheep was the most impressive. The judge arranged the contestants and their lambs into a star formation in the center of the ring and walked around and around the circle, changing directions rapidly. Since you’re always supposed to keep your animal between yourself and the judge, the kids constantly had to switch sides to keep up. They managed to pull off this incredibly challenging feat with grace and poise, effortlessly shifting their sheep from one hip to the other over and over. One of them explained to me afterward that one of the tricks is never to take your eyes off the judge. You can see that intense focus here:

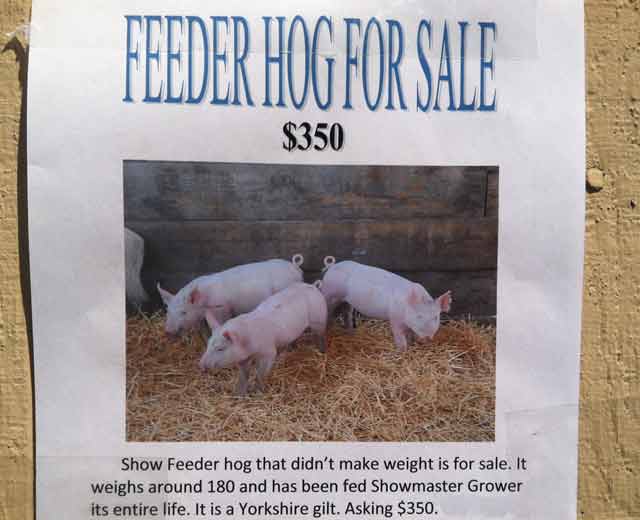

5. If your market animal doesn’t make weight, you’re kinda SOL.

At most fairs, market animals—those that will be sold for meat—must meet a certain weight requirement in order to qualify to be sold the auction. If your animal comes in under (and in some cases, over) the acceptable weight range, you can still show it (usually in a “feeder” class), but you can’t sell it at the auction. That means you might have to scramble to find a private buyer, slaughterhouse, and butcher. If you can’t sell the animal, well, you’ve just spent a lot of money—often thousands of dollars—to raise a pet. Weigh-in day can be nerve-racking for kids whose animals are right on the cusp. I saw one little boy burst into tears when his pig came in a few pounds too light. His mom turned to me and said, a tinge of panic in her voice, “What the heck am I supposed to do with this pig?”

6. Kids can make bank on their livestock projects.

For kids who raise market animals, the culmination of the fair is the auction. Some of the old-timers I talked to at the fair remember the days when it was easy to sell livestock at the fair; it was common practice for a family to buy a whole animal and use it as food for an entire year. Today, though, few people have enough storage space for a hog, let alone a 1,300-pound steer. For that reason, kids often sell their animals in quarters, or even tenths. It’s hard work to find 10 buyers, so the kids do a lot of the legwork of securing a buyer months before the fair—and some of them fetch incredible prices. On auction day at the Alameda County Fair, the resale value for hogs posted on a sign in the barn was $0.74/lb. During the portion of the hog auction that I watched, one girl sold her hog for $15/lb. Not bad for an animal that weighs somewhere in the neighborhood of 250 pounds. Kids use the money that they make on their animals for many different things: Some I talked to told me that they planned to put it away for college; others had their eye on their first car or truck.

The girl below is Mikayla, a 16-year-old member of the FFA club at Livermore High School in Livermore, California. I talked to her as she and her pig, Bubba, were waiting for their turn on the auction block. She looked kind of wistful as she scratched Bubba’s back with her pig stick (a tool that exhibitors use to guide their pigs during the show) so I asked her if she would be sad to say goodbye to the animal that she spent months raising. Not really, she said. “I need the money to make up for all the costs of raising animals.” If she made any extra, I asked, what would she spend it on? “The pigs and steer I’ll raise next year.” She grinned.