Photos: Ken Light

When I meet Javier Vaca on a dusty strip of blacktop, he’s been walking for three days. The skinny 18-year-old is being carried along in a procession of 7,000 farmworkers and farmers as it crosses California’s Central Valley, his baggy jeans and hoodie standing out amid the work boots and button-downs. He’s been told only one thing that matters: Marching 50 miles might earn him a job.

“I don’t want to jack nobody,” Vaca says, as though the thought had crossed his mind. When the housing boom imploded last year, he lost a $14-an-hour construction job, a job that had allowed this son of farmworkers to drop out of high school, buy a car, and rent an apartment for his young wife and baby in Fresno. It took him a month to find more work, this time picking peaches at less than half his previous wage. Then the worst drought in more than a decade hit, a court order to protect an endangered fish cut off water to the valley’s farmers, and an area larger than Los Angeles went fallow. Vaca now works one day a week while his family survives on welfare and food stamps. “It’s hard, man,” he says. “Everybody’s broke.”

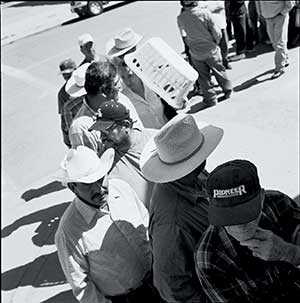

A three-hour line for a free chicken, a bag of potatoes, and some vegetables.

A three-hour line for a free chicken, a bag of potatoes, and some vegetables.

The spring morning chill becomes a broil as Vaca and his fellow marchers slowly follow a two-lane road through parched hills. A man squatting next to an ice chest on the median doles out carne asada burritos. “I’m hungry,” Vaca says with a wan smile as he stuffs one into his pants pocket and bites into another. He passes an ATV draped in an American flag, where Sharon Wakefield, an almond farmer, is resting her feet. She says she believes that the Mexicans and Central Americans who have joined the California March for Water are basically no different from her mother, who fled Oklahoma during the Great Depression to earn a pittance harvesting hay and cotton in the valley. Except this time, the state has even less to offer them: “We’ve got no water, no food, no future,” she says.

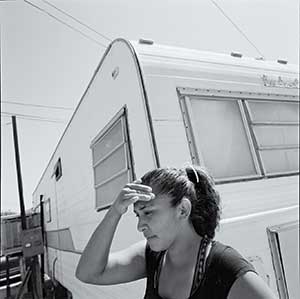

Guadalupe, 26, lives in a trailer with her five children.

Guadalupe, 26, lives in a trailer with her five children.

The Central Valley, the thin, fertile band running down the middle of California, has long boasted the world’s richest agricultural economy, reliably producing more than a quarter of the nation’s fruits, nuts, and vegetables. But it’s done so in defiance of ecological reality. The 70-year-old irrigation system that has pumped water into the otherwise arid valley is proving increasingly vulnerable to shifting weather patterns. It now appears that waterwise, 20th century California was an anomaly, a relatively wet period in the midst of a historical cycle of severe drought. And the changing climate will only magnify the problem: By the end of the century, scientists predict, Central California could experience temperatures rivaling Death Valley’s and face the loss of 90 percent of the Sierra Nevada snowpack, the region’s main water source. “Business as usual won’t work in the future,” says Eike Luedeling, an expert in plant sciences at the University of California-Davis, whose research shows that higher temperatures will likely decimate the state’s $10 billion fruit and nut industry. “Especially for tree crops, adapting will require huge investments that probably a lot of small guys can’t make anymore.”

The sudden collapse of the Central Valley’s economy illustrates how climate change can push a fragile region over the edge. Already vulnerable from rampant housing speculation and a dependence on industrial agriculture, the valley never prepared for a prolonged spate of bad weather. In 2008, local bankruptcy filings jumped 74 percent—from about 15,300 to 27,000—a rate of increase twice the national average. Three of the valley’s counties were among the nation’s six worst for foreclosures, with nearly 85,000 houses lost. The drought is expected to dry up a billion dollars in income and 35,000 jobs, adding to a statewide unemployment rate that recently hit 11.9 percent—the highest since the eve of World War II. Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger has asked the federal government to declare the region a disaster area.

On the west side of the valley, which is often last in line for deliveries from federal water projects, farmers are selling prized almond trees for firewood, fields are reverting to weed, and farmworkers who once fled droughts in Mexico are overwhelming food banks. In short, the valley is becoming what an earlier generation of refugees thought they’d escaped: an ecological catastrophe in the middle of a social and economic one—a 21st century Dust Bowl.

IF ONE COMMUNITY can illustrate all that’s going wrong in the Central Valley, it’s Mendota, a town of 9,000 midway up its west side. In the past year, its unemployment rate hit 41 percent, very close to being the highest in the nation.

In Hacienda Gardens, a subdivision on the edge of town, farmworkers and truck drivers once jumped at cheap credit and moved into brand-new $250,000 houses. On a block where about a third of those houses are vacant, I step past a pile of shattered auto glass and enter a well-kept yard where a young girl is playing. Her father, a truck driver named José Quinteros, tells me he hasn’t worked for three months for lack of produce to haul. He doesn’t know how he’ll make his $1,675 house payments. Yet he can’t stand to sell his home for what it’s currently worth—half what he paid for it three years ago—much less abandon it to the local gangs, which have been gutting the street’s empty houses. “I can’t say anything to them,” he says. “They might shoot something—my house or my car.”

Until recently, Mendota’s building boom was a small bright spot amid decades of hard times. The town calls itself the “Cantaloupe Center of the World,” though the packing plant downtown went bust about 10 years ago when growers began boxing melons in the fields using cheaper migrant labor. During the melon, tomato, and almond harvests, farmhands used to pack into backyard shacks and threadbare motels. “The conditions weren’t good, so we felt we’d go out and push for development,” Mayor Robert Silva explains as we drive in his pickup through cookie-cutter neighborhoods of new single-family homes—more than 100 were built in the town since 2007. “All this used to be cotton.” Now it is driveways and front yards overgrown with weeds.

Silva turns down Mendota’s main drag, where men mill about on every street corner, waiting for work. The most desperate will accept as little as $2 an hour. “These people are hurting big time,” says Terry Ince, an unemployed forklift operator who lives in a mobile home across the street from the old sugar-beet plant, which shut down in January. He and his girlfriend have been making ends meet by selling off their furniture and eating wild boar shot by a neighbor. “What do we have to do, put an Ethiopian baby out there with a distended tummy?” he asks. “We are in dire straits.”

The sidewalk is as crowded as the stores are empty. Silva heads into Westside Grocery, where owner and former mayor Joseph Riofrío tells me, “I need to get bailed out, man.” Riofrío’s general store, which has been in his family since the 1940s, has become little more than an occasional stoop for penniless mariachis and a collection agency for the electric company. He pulls out a stack of energy bills that customers have brought to his register and says, “Look at what they owe, and look at what they are paying.” On a $1,000 bill, $300 had been paid; on $1,200, nothing.

Late that night, Riofrío, affectionately called “El Güero”—”Whitey”—by the farmworkers, leads me down the alley behind his store, using an open cell phone to light the way. Large dogs yelp at us through backyard fences as he points out clusters of sheds and garages—rented units, “all illegal,” with as many as 20 boarders crammed inside. He waves his hand in a circle, his voice rising in frustration: “Every block in Mendota! Every single block.”

DOWN THE STREET from Westside Grocery is a boxing gym, a brick building filled with old punching bags. When I visit the next morning, volunteers have moved aside the ring to make room for 800 frozen chickens. West Side Youth, the local charity that runs the gym, is one of the only sources of free food for the western valley’s undocumented immigrants—many of whom came north to escape water scarcity and crop failure back in Mexico. Today, the monthly giveaway is scheduled for 2 p.m.; by 12:30, a line of people is wrapped around the building and halfway down the block.

The wait for a chicken, a small bag of potatoes, and some vegetables is about three hours. West Side Youth’s director, Nancy Daniel, tries to shift the elderly and disabled into a shorter line—at the last giveaway, a frail man collapsed. Her move sets off a war of elbows and shouts: “We belong over there!” “You don’t have any right to be there!” Two months earlier, a hungry crowd broke the front door in a jostle to get inside before supplies ran out.

Dead cows left on the side of the road next to a dairy.

Dead cows left on the side of the road next to a dairy.

Farther down the treeless sidewalk, Rito Sanchez waits patiently. The 30-year-old hasn’t worked since January but doesn’t have the papers to qualify for unemployment, welfare, or food stamps. And yet life was harder back in Acapulco, where “there’s no hope of anything to eat.”

Standing nearby in a tight blue-jean skirt, Marina Calixto says that picking grapes in the valley pays more than 10 times what she earned at a maquiladora near Mexico City, where she manufactured bras and underwear that she later saw for sale at Costco and Wal-Mart on this side of the border. She’s worked only two weeks in the past six months and can no longer send money home to her five daughters. “I don’t want anything but to work,” she says.

Farmworkers like Calixto and Sanchez “don’t want to realize that where an employer used to hire fifty, they are now only gonna hire five,” explains Candie Caro, service center manager for Proteus Inc., a state-funded nonprofit that assists farmworkers with food and rent while they’re retrained in trades such as truck driving. Yet most farmworkers can’t even qualify for Caro’s programs because they don’t have papers. The most she can give them is about $300 in subsidized food and rent—the only source of direct government assistance to Fresno County’s undocumented farmhands other than the Community Food Bank, where demand has more than doubled this year. “Someone who comes into the office and cries because they don’t know where their next meal is going to come from or how they are going to feed their kids—I’ve seen that,” Caro says. “You don’t know what to do. I wish we had more.”

By five in the afternoon, West Side Youth is down to its last few boxes of food. Daniel shuts the front door, cutting off 15 people still in line. A few minutes later, a haggard man in a snakeskin belt emerges with the last box and climbs into a crowded van.

That night, a West Side Youth food box sits in Alejandro Roman’s rented home, a converted barbershop on the main street where he lives with his wife, Marta, and their two teenagers. In their tiny living room, Alejandro gnaws at a toothpick as Marta knits. She is recovering from breast cancer and can’t work; he’s lost 15 percent of his hours at an almond orchard. After paying rent, utilities, and medical bills, the family lives on less than $125 a week. The orchard will probably lay off the rest of its workers if its wells fail. But the Romans, who obtained green cards several years ago, remain hopeful. “This country has given us a lot,” Marta says, setting down her needles and clasping her heart as her voice trembles. “This country, the future it has given us, is beautiful.”

A FEW MILES south of Mendota, a sign along the freeway proclaims, “Congress Created Dust Bowl.” The land around it had been green with wheat sprouts before the spring rains petered out. Then pumping restrictions put a stop to water deliveries from the federal Central Valley Project, and farmer Joe Martini gave up on harvesting a once fertile 2,300-acre hillside. Now it is nothing but powdery dirt. Martini blames the government, which has cut off water to farmers while still supplying coastal cities and maintaining water levels in the Sacramento River Delta, home to the federally protected delta smelt. “We’re not gonna survive,” he says. “We’re gonna collect some insurance this year, and then maybe next year there is no insurance and we’re done. We’ll just let it die.”

Empty houses and unfinished slabs fill a subdivision in Lathrop, California.

Empty houses and unfinished slabs fill a subdivision in Lathrop, California.

Farmers on the valley’s west side have long known that their water supply could disappear at any time, but counted on it anyway. “The dollar signs overwhelmed the warning signs,” says Richard Walker, an economic geography professor at the University of California-Berkeley and an expert on the Central Valley’s economy. “It’s the phenomenon of collective madness, collective belief, which is no different from Wall Street or American car companies.”

Some farmers cling to the hope that an ever drier California will be forced back into the business of building massive water projects. “With California’s booming population, and with the impact that global warming will cause to our snowpacks, we need more infrastructure,” Gov. Schwarzenegger said in 2007, announcing a $4.5 billion proposal for new canals, dams, and reservoirs that he claimed would help restore the ailing Sacramento delta. This summer, Democratic lawmakers sponsored a package of water bills that emphasized conservation over construction. The governor criticized the bills, even though they would allow him to appoint a panel with the authority to approve a controversial canal that would carry more water to the Central Valley and Southern California.

Standing in front of the bathtub rings of the shockingly empty San Louis Reservoir oustide Mendota, the governor quiets a cheering crowd of 10,000 at the conclusion of the four-day California March for Water. He was invited by the California Latino Water Coalition, the group of farmers and Latino politicians who organized the march to create pressure for new water projects.

“Cesar Chavez knew the power of a good march,” Schwarzenegger declares, not mentioning that the United Farm Workers, which Chavez founded, boycotted the march, calling it a front for anti-union growers. “He led by example and he never stopped trying until he found a way. And this is exactly what we are going to do.”

Waiting for free food in Mendota.

Waiting for free food in Mendota.

The desperate men and women who marched for days through the dust and heat see a quick solution to their woes: an executive order by Schwarzenegger or a deal with the Obama administration to create a to-hell-with-the-smelt exemption from the Endangered Species Act that would flood the fields again. There is little talk of the thirsty years ahead or what will have to be done to prepare for them. Someone holds a sign that says, “Don’t be a girlie man, be a governor—turn the pumps on.” Cheers break out as Schwarzenegger proclaims that he will “not quit until we get the water,” though he stops short of saying how he’ll make it happen fast enough to stave off the drought. (The State Water Project has said it will provide farmers with 40 percent of their normal water allotment for the rest of the year; the federal Bureau of Reclamation has been providing just 10 percent.)

Afterward, Joseph Riofrío shakes the governor’s hand and presses him for more details, but comes away discouraged. “I was expecting something bigger,” the former mayor admits. “But it doesn’t appear that a switch is going to be turned on.”