Jose Villarreal remembers going to bed hungry most nights during his 10 years in solitary confinement at California’s Pelican Bay State Prison. Dinner might consist of mashed potatoes, bread, and a slice of processed meat—never with salt, and always cold. Shouting through air vents between their cells, his neighbors would count the number of vegetables on their trays: eight string beans one day, 26 peas the next. “It became almost a joke,” Villarreal recalls.

This low-nutrient fare is typical of many corrections systems, which calibrate menus to meet budget demands and minimum calorie counts. Prices per meal range from about $1.30 to as low as the 15 cents that Arizona Sheriff Joe Arpaio once bragged about spending. The high-starch meals are often served up by scandal-plagued private companies. Meats are typically processed, and fresh fruit is rare, in part because it can be turned into booze.

To supplement tasteless grub, prisoners turn to the commissary, says Kimberly Dong, a Tufts University assistant professor researching prisoner health. This behind-bars bodega stocks items like Fritos and ramen, which inmates mix together to concoct dishes such as “spread,” a San Francisco County Jail specialty often made from noodles topped with hot chips, cheese sauce, and chili beans. “It’s like a carrot and a stick,” Villarreal says of the choice between commissary and facility-provided food. “But even the carrot is dipped in poison.”

This uninspiring diet is likely taking a toll on inmates’ health. It’s not just that prisoners are 6.4 times more likely to be sickened from spoiled or contaminated food than people on the outside, as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention determined in 2017. Prison food can damage their long-term wellness. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, about 44 percent of state and federal prisoners have experienced chronic disease, compared with 31 percent of the general population, even after controlling for age, sex, and race. Chronic illnesses common among prisoners—high blood pressure, diabetes, and heart problems—are linked to obesity, which is in turn associated with highly processed, high-carb jailhouse fare. And because inmates disproportionately come from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, they’re already more likely to experience chronic disease than the general public, so prison grub can exacerbate preexisting conditions.

Corrections facilities often cut corners on food in an effort to save money. But this may cost taxpayers more in the long run. According to a 2017 analysis by the Prison Policy Initiative, after staffing, health care is the public prison system’s largest expense, setting government agencies back $12.3 billion a year. Outside prisons, there’s ample evidence that improving diets can shrink health care spending: One study of food stamp recipients found that incentivizing purchases of produce while reducing soda consumption could save more than $4.3 billion in health care expenses over five years. Extrapolating from these numbers, similar changes for America’s 2.3 million prisoners could save taxpayers more than $500 million over the same time period.

That’s not counting the added savings on security, since prisoners often protest when they notice food quality deteriorating. In the last few years, dietary discontent helped spark riots in at least three states. As part of the national prison strike that started in August, prisoners in North Carolina hung a makeshift banner demanding better food. Public officials sometimes take the hint: In February, prison officials in Washington ended a nearly 1,700-person food strike at medium-security prison by agreeing to replace sugary breakfast muffins with hard-boiled eggs. Last year, Michigan upped its prison food spending by $13.7 million to replace maggot-ridden meals provided by Trinity Services Group.

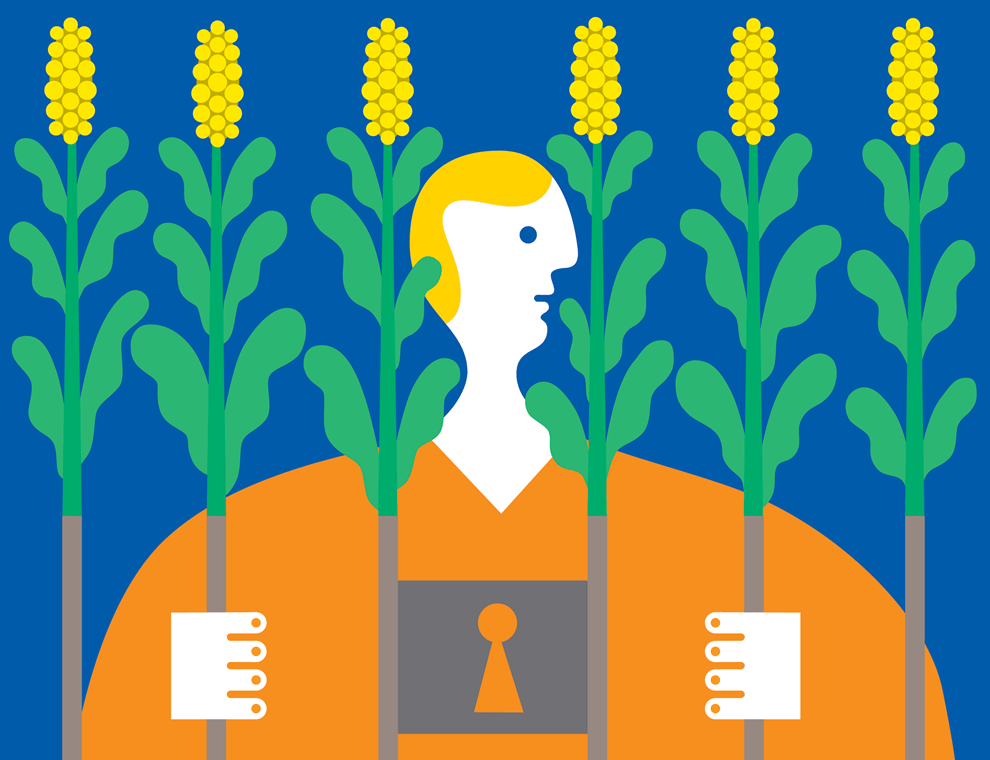

But nutritious chow doesn’t always have to cost more money. While harsh farm labor was once common at rural lockups, prison agricultural programs increasingly involve smaller-scale gardens that enable inmates to consume produce they’ve grown. Such programs have also been found to improve mental health, reduce recidivism rates, and provide job skills. One initiative, run by the Oregon-based nonprofit Growing Gardens, has graduated more than 900 inmates with gardening certificates.

A year and a half after his release, Villarreal still isn’t sure what is medically wrong with him. Lacking health insurance, he hasn’t seen a doctor since he got out, but he traces his damaged eyesight and trouble sleeping in part to a prison diet that made him physically less resilient: “If I had better, nutritious food, I think it would have helped me.”