President Donald Trump holds a medical testing swab near his nose as he tours Puritan Medical Products, a medical swab manufacturer, in early June.Patrick Semansky/AP

This story was published in partnership with ProPublica, a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up for ProPublica’s Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox as soon as they are published.

Since May, the Trump administration has paid a fledgling Texas company $7.3 million for test tubes needed in tracking the spread of the coronavirus nationwide. But, instead of the standard vials, Fillakit LLC has supplied plastic tubes made for bottling soda, which state health officials say are unusable.

The state officials say that these “preforms,” which are designed to be expanded with heat and pressure into 2-liter soda bottles, don’t fit the racks used in laboratory analysis of test samples. Even if the bottles were the right size, experts say, the company’s process likely contaminated the tubes and could yield false test results. Fillakit employees, some not wearing masks, gathered the miniature soda bottles with snow shovels and dumped them into plastic bins before squirting saline into them, all in the open air, according to former employees and ProPublica’s observation of the company’s operations.

“It wasn’t even clean, let alone sterile,” said Teresa Green, a retired science teacher who worked at Fillakit’s makeshift warehouse outside of Houston for two weeks before leaving out of frustration.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency signed its first deal with Fillakit on May 7, just six days after the company was formed by an ex-telemarketer repeatedly accused of fraudulent practices over the past two decades. Fillakit has supplied a total of more than 3 million tubes, which FEMA then approved and sent to all 50 states. If the company fulfills its contractual obligation to provide 4 million tubes, it will receive a total of $10.16 million.

Officials in New York, New Jersey, Texas and New Mexico confirmed they can’t use the Fillakit tubes. Three other states told ProPublica that they received Fillakit supplies and have not distributed them to testing sites. FEMA has asked health officials in several states to find an alternative use for the unfinished soda bottles.

“We are still trying to identify an alternative use,” said Janelle Fleming, a spokeswoman for the New Jersey Department of Health.

Fillakit owner Paul Wexler acknowledged that the tubes are normally used for soda bottles but otherwise declined to comment.

The Fillakit deal shows the perils of the Trump administration’s frantic hiring of first-time federal contractors with little scrutiny during the pandemic. The federal government has awarded more than $2 billion to first-time contractors for work related to the coronavirus, a ProPublica analysis of purchasing data shows. Many of those companies, like Fillakit, had no experience with medical supplies.

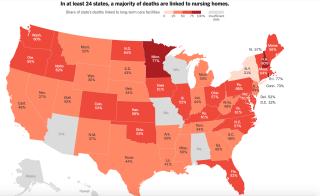

The U.S. has lagged behind many European countries in its rate of testing people for the coronavirus, partly because of supply shortages or inadequacies. Epidemiologists say testing is vital to tracking the virus and slowing transmission. In at least one state, the shipment of unusable Fillakit tubes contributed to delays in rolling out widespread testing.

“They’re the most unusable tubes I’ve ever seen,” said a top public health scientist in that state, who asked to remain anonymous to protect his job. “They’re going to sit in a warehouse and no one can use them. We won’t be able to do our full plan.”

In a written response to questions, FEMA said it inspects testing products “to ensure packaging is intact to maintain sterility; that the packing slip matches the requested product ordered, and that the vials are not leaking.” It said that “product validation” that medical supplies are effective “is reinforced at the state laboratories.”

The agency did not answer questions about the size and lack of sterilization of Fillakit’s tubes or about why it sought an alternative use for them.

Fillakit is one of more than 300 new federal contractors providing supplies related to COVID-19. A ProPublica analysis last month found about 13% of total federal government spending on pandemic-related contracts went to first-time vendors. FEMA said last month that it only pays for products once they have been delivered, minimizing the risk of wasting taxpayer dollars.

“FEMA does not enter into contracts unless it has reason to believe they will be successfully executed,” it said.

Preforms, the small tubes also known in the plastics industry as “baby soda bottles” or “blanks,” have a following among elementary school science teachers and amateur scientists, but they don’t meet rigorous laboratory standards. They’re much cheaper than glass vials and can be sealed off with a soda bottle cap. When inflated with high-pressure air, the soft plastic expands to the size of a 2-liter soda bottle.

The preforms arrive at Fillakit’s warehouse in a huge shipping container. The tubes are then shoveled into smaller bins. Workers add the saline solution and screw on caps. The tubes are then loosely piled in bags and sent to FEMA, which forwards them to the states. Typically, test tubes are individually packaged to guard against contamination.

Washington state, an epicenter of the first outbreak of the virus, got more than 76,000 Fillakit vials from FEMA. None can be used.

“They were packaged unusually,” said Frank Ameduri, a spokesman for the state Health Department. “Not in a way we’re used to seeing, and they were not labeled. Some of them have been sent to our lab for quality control. None of the vials will be used until we’ve identified what’s in them and that they are safe for use.”

About 140,000 Fillakit tubes are also shelved in Texas, where officials were slow to roll out testing. The number of confirmed cases in Texas has increased by more than one-third in the past two weeks, according to data gathered by The COVID Tracking Project.

“There were issues with the labeling, and they use saline rather than viral transport medium, so we have not used them for our testing efforts,” said Chris Van Deusen, a spokesman for the Texas health department.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has only validated one solution, known as viral transport medium, as reliable in preserving the coronavirus RNA from decay or destruction by substances in the container. However, because that medium is in short supply, the FDA has also granted an emergency authorization for other products it believes can keep the virus intact for up to three days.

Fillakit has been squirting one of the alternatives into its tubes, phosphate buffered saline, which the FDA says should be placed into “a sterile glass or plastic vial.”

A spokeswoman for the Maryland-based Association of Public Health Laboratories, a membership organization that writes best practices and helps connect public health labs with government agencies, said it has heard rumblings about Fillakit’s tubes but “nothing deadly.”

“The bigger issue is the size of the tubes,” said the spokeswoman, Michelle Forman. “They are an unusual shape so they don’t fit racks, and we are getting lots of pushback about how difficult it is to work with them from our clinical partners.”

Richard Loeb, a contract law expert at the University of Baltimore, said FEMA has the power to claw back money paid to contractors, remove them from the government’s list of approved vendors or refer them to the agency’s inspector general.

“It’s outrageous enough that they [FEMA] ordered something to test for COVID-19, and they got something that can’t be used to test for COVID-19,” Loeb said. “I still am a little bit troubled as to why FEMA accepted them. … They may have stupidly accepted something that was nonconforming.”

Wexler, Fillakit’s owner, has a background in law and real estate, not medical supplies. In 2012, the Federal Trade Commission accused Wexler and his telemarketing firm of illegal robocalling, making unauthorized charges to consumers’ bank accounts and falsely claiming to be a nonprofit organization. Wexler’s firm allegedly misrepresented itself as a credit counseling service for several years, charging customers for work it did not do, according to court records.

Wexler, who denied the charges, settled the case a year later. The settlement banned him from offering debt relief services—but not from being a federal contractor—and imposed a $2.7 million judgment.

Fillakit and another Wexler company, Cleargate Labs, operate out of the same warehouse in The Woodlands, a sprawling Houston suburb.

Cleargate describes itself as a “network of primary clinical laboratories” on its website. Last year, the company cold-called an elderly Iowa woman, told her that it was marketing a DNA screening for cancer genes and offered to send her testing supplies in exchange for her Medicare number, the Tampa Bay Times reported. Suspecting a scam, the woman reported the company to local law enforcement. Cleargate did not bill her and was not charged with a crime.

Three former Fillakit employees said that its process was unsterile. Workers shoveled up the tubes from unsanitary surfaces. The liquid that they added to each tube to preserve samples for lab analysis was kept in trays exposed to the air, which was whipped around by large fans.

Standards were compromised in the rush to meet productivity goals, Green said. “At the beginning, they were being picky, saying, ‘You have to make sure it’s at least 2 milliliters.’ And sometimes there were tubes that didn’t have any [solution] in there,” she said.

Wexler would come in and “cuss and scream at everybody in this warehouse about how nobody’s paying attention to what they’re doing,” she said.

Wexler and Stephen Wachtler, a manager at Cleargate and Fillakit, “were telling us, ‘Yeah, we gotta have four bins by lunch,’” Green said. “‘We gotta have 10 bins before you leave at 5 o’clock. Work faster, work faster.’”

Green said that few employees at the company had backgrounds in science or medicine. In May, during Fillakit’s first week of operations, the company did not provide workers with face masks, she said, raising concerns that fluid from their noses and mouths could land inside the tubes. Later, supervisors did hand out masks but did not require employees to wear them.

On June 10, a ProPublica reporter observed workers, some not wearing masks, standing over snow shovels and bins of tiny soda bottles.

Wexler and workers loaded a shipment of tubes into an Enterprise rental truck, which lacked the refrigeration that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention say is needed to safely transport legitimate testing supplies.

Wexler denied a request to tour the warehouse. Asked about the lack of sterile conditions and the use of soda preforms, Wexler screamed, “What’s your problem, man?”

Michelle Hardy, a retired nurse who worked at Fillakit through June 10, said her concerns about contamination were dismissed by Wachtler. He did not respond to requests for comment.

“I kind of said to Stephen, ‘Is this supposed to be, like, clean technique, or sterile technique or what?’” Hardy said. “He’s like: ‘No, it’s fine. It’s fine what you’re doing because they’re just testing for COVID, and so if there’s any other bacteria or viruses in there then it’s not going to show up.’”

That’s not true, according to Vjollca Konjufca, an associate professor of microbiology at Southern Illinois University. If Fillakit employees were infected, they might have contaminated the tubes with their own virus, potentially causing false test results, she said.

Konjufca was part of a team at her university that manufactured the viral transport solution validated by the FDA. She said they followed strict protocols to ensure tests aren’t contaminated.

“We filter-sterilize, and then we add antibiotics,” Konjufca said. “The whole work is handled under a biosafety hood … so it does not allow any sort of air from the room, particulates or whatever, to get into your vials.”

There are many ways to mess up medical testing, so careful manufacturing is vital. Some substances in saliva or the plastic vials can damage virus RNA and alter test results, Konjufca said.

“You cannot just makeshift use soda bottles to make tubes,” she said. “You have enzymes in there and you have contaminants that can mess up the results.”