Nicholas Kamm/Getty

Marine One lands on the White House lawn. Donald Trump, still sick and contagious after being treated for COVID-19 at Walter Reed Medical Center, strides alone across the grass while cameras flash. Then, having climbed the steps to the balcony, he dramatically strips off his mask and salutes the helicopter as it rises toward the Washington Monument. In one of the propaganda videos of the scene uploaded to the president’s Twitter account, heroic music booms in the background—an instrumental version of a track called “Believe” from an album titled “Epic Male Songs.”

In the last few weeks, Trump and his supporters’ attempts to project masculine strength and dominance have reached literally toxic levels. “President Trump won’t have to recover from COVID. COVID will have to recover from President Trump,” Rep. Matt Gaetz (R-Fla.) tweeted. Sen. Kelly Loeffler (R-Ga.) posted an edited video of Trump wrestling the coronavirus to the ground, WWE-style. Much of the projections of the president’s manliness is tied up in the idea that he doesn’t need a mask because he is tough. “I don’t wear masks like him,” Trump said dismissively at the September 29 debate against Joe Biden. “Every time you see him, he’s got a mask. He could be speaking 200 feet away from them and he shows up with the biggest mask I’ve ever seen.” Earlier this week, he taunted House Majority Leader Nancy Pelosi by tweeting, “Wear your mask in the ‘beauty’ parlor, Nancy!”

To untangle the political and gender dynamics of Trump’s blustery response to the coronavirus and his own infection I spoke with Christina Wolbrecht, a Notre Dame political science professor who coedits the journal Politics & Gender. This spring, Wolbrecht and her colleagues put out a call for papers about COVID-19, and received multiple submissions about men and mask-wearing. Three studies published in the resulting series this summer independently demonstrated links between gender identity, including sexist attitudes, and whether someone is likely to wear a mask.

Masks are a piece of cloth that you wear on your face. They protect you and the people around you. They’re not inherently a gender-related thing, but surveys have shown women are wearing them more often than men. What do we know about why that is?

Why do some people wear masks and others don’t? One predictor is your partisanship. We know in general that Democrats, at least up to recently, have been more likely to wear masks than Republicans. We know there’s some differences in terms of age. It turns out that another thing that explains the difference is gender identity, or the extent to which you hold sexist views. In our culture, traditional masculinity is understood as strength, vigor, and health—as not being dependent upon other people. And so to act ill, to be seen as weak, is seen as feminine. If you value masculinity, you want to move away from anything that associates you with weakness.

People who are more likely to think that women complain about things too much, and call things discrimination that aren’t, or that there should be more traditional roles in the family, are less likely to wear masks. Similarly, we see people who describe themselves as “completely masculine” and say that being masculine is very central to their sense of who they are, are less likely to wear masks. These studies suggest that the impact of having those sorts of views is bigger than, say, partisanship.

What are some qualities of masculine ideology in America that are antithetical to wearing a mask?

Public health experts have told us for a long time that men are less likely to go in for proactive doctors’ appointments, less likely to take advantage of lots of prophylactic medicines—and as a result, when they feel sick, they deny that they’re sick, go to the doctors later, et cetera—with real health consequences. This is one of the reasons why men die earlier. Public health experts for a long time have told us this is about masculinity.

It also [includes] gendered political stereotypes. There’s a long tradition in American politics and Western political development of understanding manhood—and, really, the conditions for citizenship—in these sorts of terms. You’ve got to be strong, you’ve got to be able to defend the nation, you need vigor and energy, you need to act independently. Women traditionally were understood to not have those characteristics. And that was one of the reasons they were excluded from things like the ballot box. There’s the fainting spells and the whole stereotype of women as lacking physical endurance—all associating women and illness as an opposite to masculinity.

There’s also an association between people who might subscribe to more traditional masculinity and Republicanism, right? Maybe that’s my bias showing—

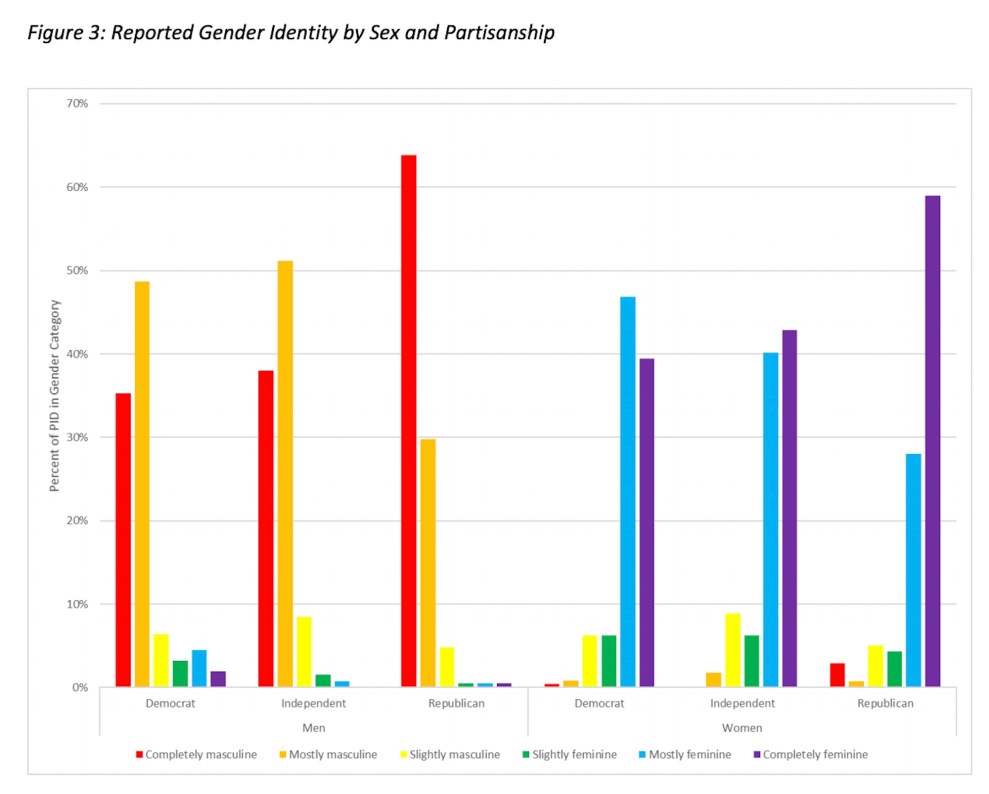

No! I could show you some graphs. The percentage of men in the Republican Party who describe themselves as completely masculine and say they really care about masculinity is higher than the percentage of men who say that in the Democratic Party.

One answer might be, “Oh, well, men are more likely to wear masks than women. That must be because men are more likely to be Republicans than women”—which is, in fact, true. Or you could say, “Oh, well, sexism predicts whether or not you wear a mask, but it turns out that all the sexists are Republicans and none of the Democrats are, and so really what you think is sexism is about party.” The truth is, while Democrats may be more likely to wear masks than Republicans, Democrats who hold sexist beliefs or really value being thought of as masculine are going to be less likely to do so. But a sexist Democrat still looks a bit different from the sexist Republican.

It’s like, the Venn diagram of bro-ey alpha guys, Trumpers, and non-mask wearers isn’t exactly a circle, but it’s pretty round.

That’s right.

We’ve all seen examples of “masculine” masks in pop culture—superhero movies, comics, westerns. Why are masks gendered as tough and masculine there, and as feminine in the context of this pandemic?

Nobody thinks it’s not masculine to wear a bulletproof vest, right? Protecting yourself in that way somehow means that you’re engaged in a firefight. So that’s fine, but [masks are] not. This is where the importance of framing is really important. Because it’s framed not as “You’re going off to battle, so you wear a cool bulletproof vest,” but rather, “There’s the sickness going around that makes you really tired and sniffily and may actually kill you,” [mask wearing] in some sense falls into “Real men don’t eat salads, real men don’t watch their blood pressure, real men don’t do all these things that we probably want to do if we’re trying to maintain our health.” It’s a sign of weakness.

Of course, the other piece is the cues that we’re given. Tomi Lahren, the conservative commentator, made a joke on Twitter about how Joe Biden should just get a purse to go with his mask. Being called a girl is about as unmasculine as you possibly can be. There’s been a lot of cues, especially among conservatives, as part of a broader sort of attack on the science of coronavirus. I think those messages have been pretty strong.

Especially in the White House video in which Trump, upon coming back from Walter Reed Medical Center and taking off his mask before he walks back into his workplace, announced that Americans should not let the virus “dominate” them. Is that gendered, or am I being sensitive?

Oh, my God, no. You want [to know] is this a political thing? Is this a gender thing? What I want to emphasize and say very clearly is that you cannot distinguish the two. From time immemorial, our ideas about leadership and power have been deeply gendered. That entire video, of the strong man who walks across the grass by himself, no one helps him get there, he is a leader, he goes first—that’s a very specific idea about how power is exercised. It’s not collaborative, it doesn’t take a village, it’s not in cooperation. It’s very much embodied in one person who has a very particular kind of power and strength to go up into this great, grand building, and to stand there under the lights, and the very militarized Marine One helicopter.

I don’t know if you’ve seen the more “manly” masks that are out there—the Punisher masks among them. What do they tell us about the dynamics at play here?

I would put those in the same category as the masks that match my shoes. The political theorist Judith Butler is famous for, among other things, describing gender as performative—that the way in which we present ourselves, walk, talk, dress, the accessories we wear, all of it is consciously or subconsciously a way that we express our identity. This is central to our understandings of politics as well. Partisan identities, racial identities, class identities are all things that we put on and project—and so it’s not surprising that very quickly, a market has gone grown up to provide for every possible identity you can think of. The sports identity, patriotic identity, you name it. And, in a different way but still gendered, all the RBG masks.

In the research that you’ve reviewed, is there anything about women who hold traditional beliefs about femininity and how that affects mask wearing?

The stuff on the side of women is more complicated. The effects are less consistent, and often less strong, but the same patterns hold. Preferring a traditional family, thinking that women are just out there accusing men of discrimination and unfairly trying to get an advantage—those are not views that only men hold. There are considerable swaths of the female population in the United States who hold those sorts of views as well. The research we’ve seen does suggest that women who hold what we would categorize as more sexist ideas and beliefs are less likely to wear masks, or to support mask wearing, or to support closing schools.