Don McGahn showed up for a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing on September 27, 2018. aul Loeb/CNP via ZUMA Wire

Remember Don McGahn? On Friday, Donald Trump’s ex-White House counsel will testify before the House Judiciary Committee about the former president’s efforts to obstruct the Russia investigation, an appearance so overdue that its main message will be an ironic reminder. The cover-up McGahn is supposed to shed light on was a smashing success.

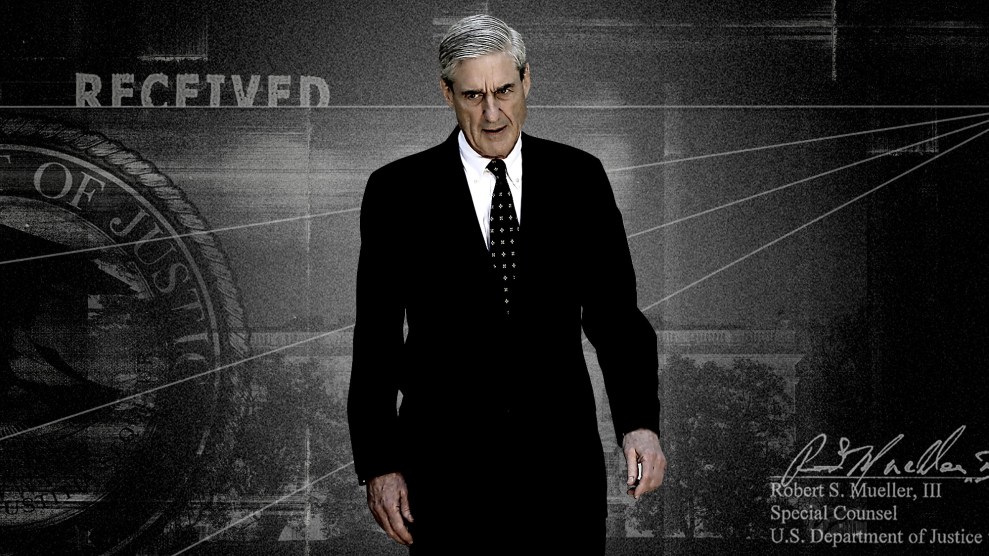

The committee subpoenaed McGahn way back in May 2019, demanding that he share information he had already given special counsel Robert Mueller about Trump’s apparent attempts to obstruct justice. Among other things, McGahn could have detailed how Trump had pushed him to fire Mueller, an instruction McGahn refused, and then had subsequently urged McGahn to lie about the incident, another order McGahan didn’t obey. The Judiciary Committee wanted McGahn to testify on camera to help them make the case for impeachment.

But McGahn, on Trump’s orders, refused to appear, asserting executive privilege in an early instance of what became the de facto White House policy of stonewalling all congressional oversight. The committee sued to enforce the subpoena. The Justice Department opposed it, and a two-year court battle ensued, ending only last month in an agreement for McGahn to testify before the committee, but only behind closed doors, The committee will release a transcript in a week or so. But there is little chance McGahn will divulge anything new. The committee has agreed to ask him only about information attributed to him in Mueller’s April 2019 report.

With Trump six months out of office, impeached twice for conduct unrelated to what McGahn will talk about, the original purpose of his appearance is long gone. So what’s the point?

Arguably the committee is showing it will not be deterred by stonewalling.

“We can’t just pretend that the president’s obstruction crimes never happened,” said Norman Eisen, who worked as a lawyer for the House Judiciary Committee from 2019 to 2020, “We can’t just forget about it. Congress is continuing to do what they can to ensure a spotlight continues to be shined on that.”

Eisen says federal prosecutors could still charge Trump with obstructing justice and that the committee’s work may increase the odds of such a prosecution. And while there is no sign that will occur, Eisen notes that the panel can also advance legislation “to prevent these kinds of apparent offenses from occurring in the future,” perhaps by helping build support for proposals to force courts to more quickly review cases involving congressional subpoenas and curtail the president’s power to grant pardons, among other reforms.

Maybe. But it is difficult to deny that blocking access to McGahn and thwarting Congress on everything else related to Mueller’s report worked for Trump. He wasn’t impeached for that. And future presidents facing scandal have every incentive to follow Trump’s lead.

In fact, by agreeing to a deal (an outcome strongly encouraged by judges in disputes between branches of government), the House committee sacrificed the possibility that the full US Court of Appeals would uphold Congress’ power to go to court to enforce subpoenas. That means that “the next time a fight emerges over a subpoena from the House to the executive branch, the Justice Department will be able to start fresh in prolonged litigation over that unresolved issue,” the New York Times reported.

Trump’s efforts to block investigators were broader than telling former aides not to talk to Congress. Trump’s bids to fire Mueller, the same conduct McGahn is supposed to discuss, rattled the special counsel’s office and contributed to Mueller’s decision to curtail the probe and use extreme caution in issuing public pronouncement about Trump, according to Andrew Weissmann, a former Mueller deputy.

Mueller, crucially, decided that he could not say explicitly what his report implies—that Trump committed multiple acts of obstruction of justice. Mueller determined that since Justice Department policy bars indicting a sitting president, it would be unfair to Trump to accuse him of crimes he could not contest in court. This was despite the fact that Trump, who had 60 million Twitter followers at the time, would have had no problem defending himself publicly.

Mueller’s caution was exploited by Attorney General William Barr, who misled the public about what the special counsel had found before Mueller’s was publicly released. Mueller’s report called for Congress to consider the evidence he had compiled of Trump’s obstruction, yet Barr claimed that role for himself, announcing two days after receiving the 450-page report that Trump had not violated the law. Barr later claimed, falsely, that Mueller simply had not found enough evidence of obstruction to charge Trump and that the special counsel’s decision was not the result of the department’s policy..

Last month, US District Court Judge Amy Berman Jackson accused Barr of making “disingenuous” claim about whether Trump obstructed justice. While ordering the release of a memo Barr received in 2019 on that topic, Jackson questioned the honesty of Barr’s public claims, saying they aimed to “create a narrative to counter the special counsel’s findings and cast the President in the most positive light possible.” (Last year, another federal judge, US District Court Judge Reggie Walton, similarly said that Barr had showed a “lack of candor” in his public descriptions of Mueller’s report. Many Democrats and others have also accused Barr of lying to Congress under oath.)

Barr hasn’t responded to Jackson. But his lies worked at the time. They fostered the public perception that Mueller had cleared Trump of conspiring with Russia and obstructing justice, though Mueller did neither. And congressional Democrats, wary of challenging that public view, backed down on Russia. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi nixed calls to include obstruction of justice among charges the House cited in December 2019 to impeach Trump for extorting Ukraine for dirt on Joe Biden.

Trump’s current legal woes do not include any evident prospect of federal charges. And players like Barr and McGahn, along with aides who Trump pardoned, face no obvious consequences for having helped to stymie investigators.

In addition, even under Biden, the Justice Department, keen to protect executive branch ability to blow off Congress, is siding against Hill Democrats and transparency advocates to help Trump keep information on the Russia probe secret. Biden’s Justice Department argued to keep private the Justice Department memo on obstruction of justice that Jackson ordered released. And Biden’s Justice Department took the same position on McGahn’s testimony that Trump’s did: Congress lacks the right to sue to enforce subpoenas.

Rep. Jerrold Nadler (D-NY.), the House Judiciary Committee chairman, said last month that McGahn’s refusal to testify was part of Trump’s “dangerous campaign of unprecedented obstruction.” And he contended that McGahn’s testimony will “begin to bring that era of obstruction to an end.” That would be nice. But in truth, Trump’s obstruction is outlasting Trump.