Demonstrators dance in the street outside the Pennsylvania Convention Center, where votes were still being counted on the Thursday following Election Day.Rebecca Blackwell/AP

Amanda Mcillmurray, sporting a yellow “Voters Decide” mask on Thursday, has seen her share of protests as political director of Reclaim Philadelphia, an activist organization founded in 2016 by former Bernie Sanders campaign staffers. But even she imagined that the scene outside of the Pennsylvania Convention Center, pitting flag-waving Trump supporters against a sea of progressive activists, would be a “more tense protest.”

Instead, what she and dozens of reporters and activists found was more akin to a family reunion or block party, complete with music and dancing. “Philly people know how to party,” she told me. “We do this work because we care about each other, we care about our communities. It just makes sense for us to bring radical joy and love into everything that we do.”

The progressive movement in Philadelphia, with years of experience in coalition-building and mobilization, was ready to hit the streets in an uncertain post-election period with help from national groups and nonpartisan organizations like Election Defenders, whose “Joy to the Polls” effort, which had live music greet voters at polling stations across the country, was central to the musical vibe outside the convention center. Even as the coronavirus pandemic has kept people indoors more than usual, Philadelphia organizers have rallied throughout the summer and fall in protests following the killing of George Floyd and the grand jury decision exonerating three Louisville police officers in the death of Breonna Taylor. Last month, the death of Walter Wallace, a West Philadelphia man who had been experiencing a mental health episode, sparked widespread protests, a citywide curfew, and the arrival of National Guard units.

A contentious election, held during a pandemic at a time when the national spotlight is on Philadelphia, was just the latest thing demanding attention from activists. “This moment has been a crash course in how our electoral process works,” Bryan Mercer, executive director of the Movement Alliance Project, a Philadelphia activist organization founded in 2005, told the Philadelphia Inquirer last month.

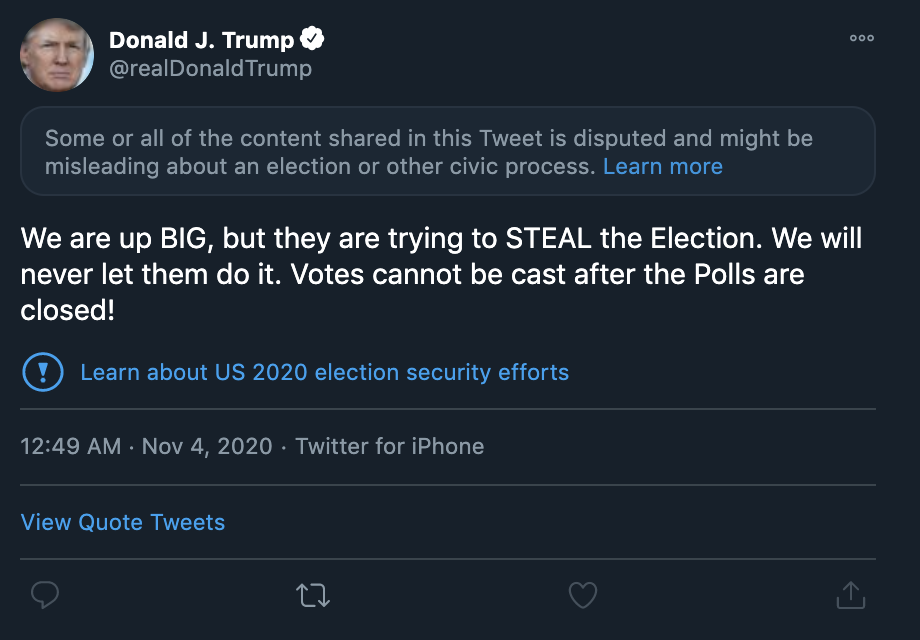

Since the first presidential debate, when Donald Trump ominously suggested that “bad things happen in Philadelphia,” the president’s campaign and its supporters have sowed doubt and confusion about the voting process in Pennsylvania and other swing states. On Wednesday, the Trump campaign sued to stop the vote count in Pennsylvania, and Trump ally Lou Dobbs urged viewers of Fox Business show that night to “surround” Philadelphia and apply a “real rigorous, demanding presence” in the rooms where polls were being counted.

Several Trump supporters, organized by conservative groups like Tea Party Patriots Action and FreedomWorks, stood outside the convention center waving flags and attracting throngs of attention, while journalists from as far away as Australia lobbed questions at them. Occasionally, the Trump supporters, who were separated from the liberal protesters by a police barricade, traded jeers or, in one woman’s case, loudly yelled “NOT TODAY, SATAN!” through a megaphone. But mostly the crowds ignored each other and, as the afternoon went on, the crowd of Trump supporters dwindled.

At around 2:15 p.m., several organizers carried eight Domino’s pizzas over to the intersection of 12th and Arch streets, outside the convention center. Next to the pizzas, Robin Hynicka, lead pastor at nearby Arch Street United Methodist Church, a close partner to the city’s progressive movement, handed out masks, water, and mini-bottles of hand sanitizer. “We’re holding on to a block party atmosphere so that every vote gets counted in Philadelphia,” he told me.

One Trump supporter who stood outside the barricade was Dion Cini, a New Yorker best known for viral stunts where he displays a Trump flag in public locations. He used his popular Facebook page to urge Trump supporters to “stop the steal” in Philadelphia, Detroit, and Phoenix, but seemed reticent to draw a comparison with his work and the type of protesting by liberals that Trump supporters often decry as violent or hostile. “I’ve never protested in my life,” he told me. “I rally. Big difference.” Pointing to the group of progressive protesters, he said, “They protest and their protest turns into violence and then, somehow, some way, they win.”

That caricature certainly doesn’t apply to Thursday’s protesters, but also fails to capture how remarkably organized and collaborative the progressive movement has become in Philadelphia. Kendra Brooks, one of the speakers at Thursday’s rally, was elected to the City Council last year as a member of the Working Families Party, the first time a council seat reserved for non-Democrats had been filled by anyone but a Republican. One of several marquee progressive victories in Philadelphia—along with the election of reformist district attorney Larry Krasner in 2017—Brooks’ rise to political prominence crystallized the waning impact of the mainstream Democratic establishment that has held sway in the city for decades.

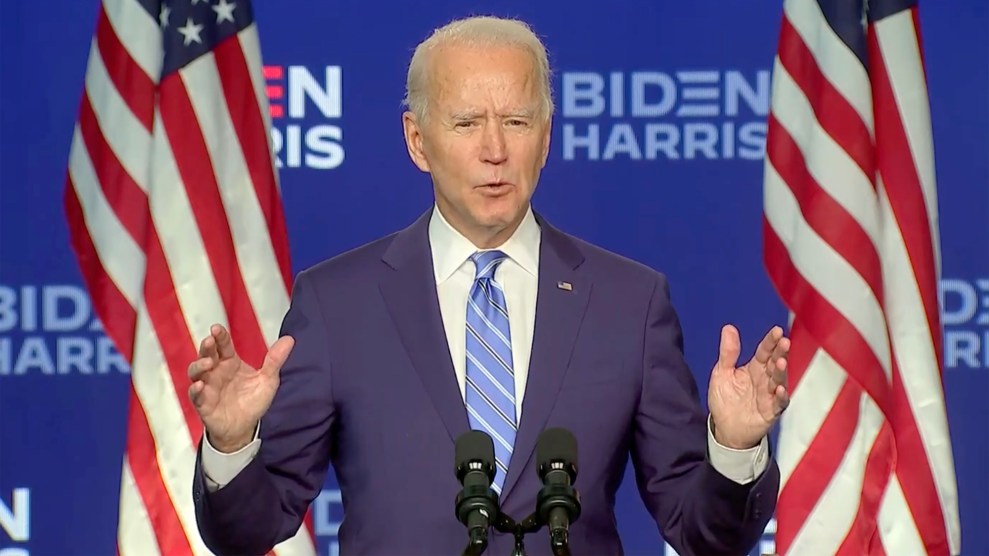

For Brooks, the movement to shield the vote count from political interference has less to do with Biden—who virtually none of the organizing groups endorsed in the Democratic primary—and more to do with protecting the political interests of voters disillusioned with politics and marginalized by the two major parties. “We drove so many people to the polls by pushing, pushing, pushing young folks to vote, folks who aren’t usually involved in the process to vote,” she told me. “And we need to show them that we will stand with them and make sure that their vote is counted.”

Before entering politics, Brooks and Helen Gym, another council member who spoke on Thursday, were active in activism around public education—a particularly potent issue in Philadelphia, the poorest big city in the United States. They are fluent in the language of movement building and activism that sees injustice across social, economic, and racial lines as unmistakably interconnected.

Not even the post-election chaos could be divorced from Philadelphia’s existing problems. On Wednesday night, city officials released bodycam footage taken by the officers who killed Wallace, sparking more protests. “I had meetings all morning about police reform,” Brooks told me. “The city is still running, regardless. I still have my city responsibilities. But on the other side, I have a responsibility to my constituents and that’s why I’m out here.”