Kristoffer Tripplaar/ZUMA

The conventional snark on President Barack Obama’s Syria strategy is that he’s made a hash of it. The other day, I bumped into a former Obama administration official who informed me his jaw hit the floor when he watched the president on Saturday announce he would seek congressional authorization for a limited military strike on Bashar al-Assad’s regime in retaliation for its presumed use of chemical weapons last month. “Why make this more complicated?” this frustrated ex-official asked. And a House Democrat I encountered who supports a strike—and who has been enlisted by House Democrat leader Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) to persuade progressive Ds to vote for the president’s Syria resolution—was apoplectic: “The one thing this president knows is how dysfunctional and obstructionist the [Republican-controlled] House is. Why would he stake his presidency on it?” This lawmaker was pessimistic that enough House Democrats could be coaxed into voting for the resolution; he was not making any progress with his partymates opposed to a strike. “We don’t have the votes,” he declared—and he was damn angry at Obama.

With his decision to seek congressional approval for an attack, Obama created a political whirlpool. He exacerbated the growing schism on the right that pits tea party isolationists—led by possible presidential candidate Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.), with Sens. Ted Cruz (R-Tex.) and Marco Rubio (R-Fla.), other likely 2016ers, rushing to catch up—versus the coalition of hawks commanded by Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.) and neocons who yearn for a deeper and larger intervention in Syria than the president envisions. This split has the potential to turn into an ideological civil war within the GOP during the next presidential campaign. Meanwhile, House Republicans are deeply divided (unlike during the run-up to the Iraq war), with Speaker John Boehner (R-Ohio) and his leadership crew on the president’s side and rank-and-file House GOPers, enwrapped in Obama hatred, accusing the president of misleading the world and engaging in conspiratorial warmongering.

That’s the good news for the White House. The bad news is that the president has sparked the same thing on his own side. Many Democrats, especially in the House, feel torn between backing the leader of their party and their anti-war inclinations, which are certainly buttressed by widespread popular opposition to the strike. Granted, Democrats are used to confronting such tensions. (Almost all House and Senate Republicans voted for the Iraq War, but half the Democrats backed it, and half opposed it.) Yet this time the decision for many Democrats is more difficult due to the overarching political context. The president is about to engage the Republicans on two contentious fronts: a battle over the funding of the federal government (with a possible government shutdown at risk) and a fight over raising the debt ceiling (with a possible financial crisis at risk). And tea party Republicans are attempting to bring Obamacare into the brewing mess. (Their threat: If you don’t defund Obamacare, we’ll shut down the government.) With all this looming, Democrats certainly don’t want Obama’s standing weakened, and if he loses the vote on the Syria resolution, he will be diminished.

And maybe not just at home. If Obama fails to win congressional support—at the moment, his prospects are much better in the Senate than the House—frenemies and foes abroad will no doubt consider this a sign of infirmity. And the president will confront yet another dilemma: whether to proceed with an attack. He has not ruled out an assault unauthorized by Congress. Yet if he bombs Syria without the support of Congress (or with only the Senate backing him)—a prospect discounted by several former Obama officials—he may well prompt a political crisis at home. (Yes, some GOPers will call for impeachment.) At the least, he will face a fusillade of criticism and the charge that he’s a hypocrite who only abides by the Constitution when it suits him. Yet if the resolution does not pass both houses of Congress and Obama stands down on Syria—after having hurled exceedingly tough talk—he will probably appear weak to allies and enemies overseas.

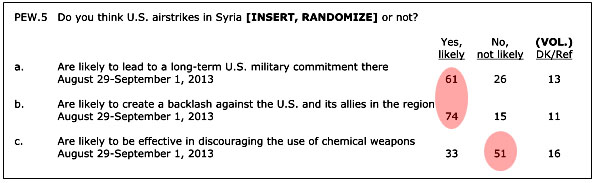

Given all these swirling and complicated political dynamics, why did Obama grant Congress the right to hold him hostage? Some cynics have suggested that he might be seeking a way out of the corner he red-lined himself into. The polls show a strike would likely be highly unpopular among American voters, and experts of various ideological bents have raised serious questions about the efficacy and impact of a limited US military assault designed to deter Assad from the further use of chemical weapons. If Congress doesn’t green light the endeavor, Obama can say he gave it a shot and retreat. Others have slammed Obama for not having the spine to go it alone, speculating he felt the need for political cover. But there’s an alternative explanation: He’s doing the right thing—or what he believes is the right thing.

A former senior Obama adviser who still works with the White House says, “Look at this. Is there any other explanation, other than he thinks this is what he ought to do?” Meaning that Obama, the former law professor, is paying heed to the constitutional notion that the president shares war-making responsibility with Congress. Though this question has long been a source of unresolved conflict between presidents and legislators—and Obama did not seek congressional approval for the military action in Libya and has ordered drone strikes without official Capitol Hill backing—he does appear to be sympathetic to the idea that a president does not possess unhindered and unchecked war-making authority. During the 2008 campaign, he declared, “The president does not have power under the Constitution to unilaterally authorize a military attack in a situation that does not involve stopping an actual or imminent threat to the nation.”

In Libya, Obama did not act in sync with his campaign statement. But in that instance, past and present Obama aides have contended, the president had only two days or so to mount a strike (with European and Arab allies) to prevent a possible slaughter of Libyan civilians. So Obama sidestepped his previously held view, put that particular principle on hold—and took the hit.

This time around, as Obama has pointed out, he does not have to move quickly to thwart an imminent threat. Consequently, he has had the chance to proceed according to constitutional rules (as he sees them). “I think it was pretty clear to him,” says a former senior White House official, “that if he blew past Congress this time, that would be it.” That is, the idea of joint executive-legislative responsibility for war would be trampled so far into the ground it could remain buried for years to come.

Though Obama has aimed to preserve a flexible degree of executive privilege—and he still might order a strike on Syria without Congress’ okay—he didn’t want to do long-term damage to this central constitutional principle. Sure, he’ll bend it, but he won’t break it. Guiding him, this former aide suggested, was that trademarked Obama nuance-ism that blends pragmatism and principle in a manner that hardly lends itself to crystal-clear messaging.

Is this what led Obama to decide to seek congressional approval and trigger the dust-up that is now bedeviling both parties and that may inflict damage upon his presidency? If so, part of Obama must believe deeply in this constitutional principle, for he’s causing plenty of heartburn—if not heartbreak—for his political allies, his supporters, and for himself.