For nearly a century, the musicians playing and promoting old-time string band and bluegrass music have tended to be white. That’s not merely a cultural trend, explains Jake Blount, a Black fiddler and banjo player who also has a degree in ethnomusicology. As he told me for a recent piece:

In the 1920s, record labels began differentiating between “race records” and “hillbilly music,” sometimes erasing Black musicians from the hillbilly records by not crediting them. “They recorded Black people playing blues and jazz, and white people playing fiddle and banjo music. They marketed the Black people to Black people and the white people to white people,” Blount says. “By doing that, they created a financial incentive for those traditions to stop interweaving with one another and stop communicating.”

This segregation catalyzed a Black exodus from old-time music during the 20th century, even though Black musicians were the ones who had helped alchemize the homegrown concoction of English ballads, Celtic fiddle songs, blues and spirituals, and African instrumentation that eventually gave rise to country and bluegrass music.

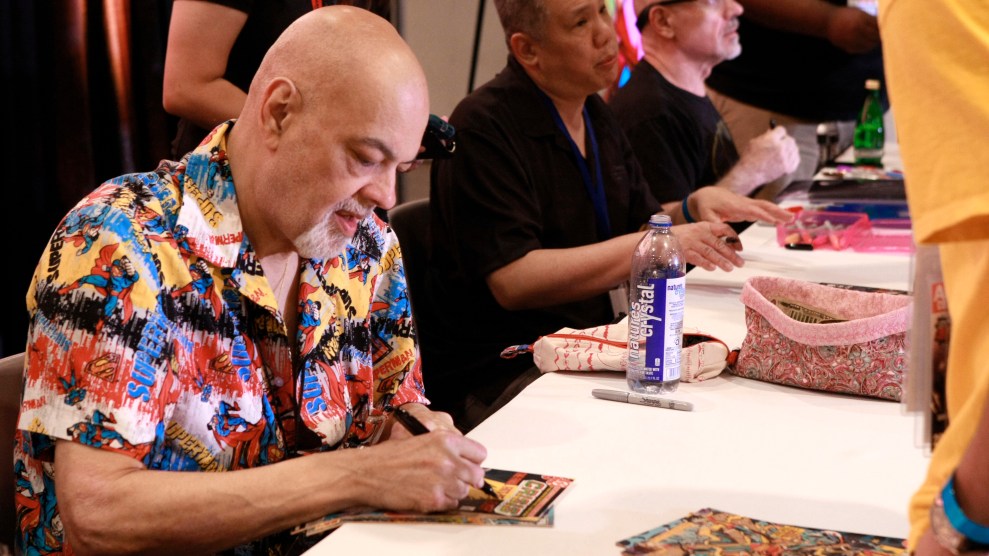

Blount is part of a new generation of artists picking up where their ancestors left off. With his 2020 album, Spider Tales, one of my favorite of the year, Blount summons a rich history of American folk songs written and sung by Black and Indigenous musicians, tunes that have been there throughout the history of this country even if they were obscured, underpromoted, or drowned out, or audiences simply weren’t paying enough attention. “I see my role as someone who’s in the middle of all of those genres,” Blount says, “to start to undo that damage and put these things back in dialogue with one another.”

Listen to some of Blount’s songs and read my interview with the musician here.