Paige Vickers/Vox; Getty

This story was originally published by Vox.com and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

You wouldn’t expect to find the linchpin of the global microchip industry tucked away in a Blue Ridge Mountains town, but it’s there. Scattered across the outskirts of Spruce Pine, a series of mines has been extracting some of the purest quartz on Earth for decades. The resource is so essential that almost every advanced microchip produced today touches it during the manufacturing process.

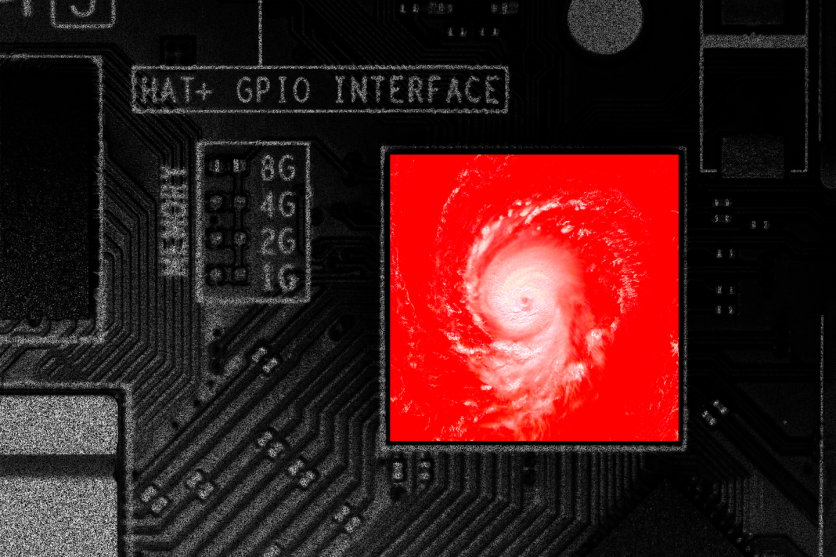

Those mines are now closed indefinitely, after Hurricane Helene dumped 2 feet of water on Spruce Pine, devastating the area. And with this singular supply of ultra-pure quartz cut off for the foreseeable future, the world’s supply of chips hangs in the balance.

To be clear, Spruce Pine is not the only place on the planet with high-purity quartz. Quartz, which is mostly made of crystallized silicon, is the second-most abundant mineral in Earth’s crust. But what’s beneath Spruce Pine is special.

Spruce Pine lies along a ridge of the Appalachian Mountains that were formed when two paleocontinents collided to create a single landmass, Pangea, some 380 million years ago. The precise conditions around that collision meant few impurities mixed into the molten minerals that swirled miles beneath the surface. Now cooled and worn, the rocks around Spruce Pine has the look of a dirty snowball thanks to a combination of feldspar, mica, and quartz. When ground up, it just looks like white sand, but when isolated, the quartz is perhaps the purest in the world.

“It’s not like the silicon that comes out of the ground in North Carolina then becomes part of a silicon chip,” said Ed Conway, author of Material World. “But you can’t make a silicon chip without it.”

Because it needs minimal refining after being pulled from the ground, Spruce Pine quartz is also cheaper than the competition. That doesn’t mean it’s cheap. High-purity Spruce Pine quartz can sell for up to $20,000 per ton, and the waste materials from mining are pristine enough that they’re even used to fill the bunkers at the Augusta National Golf Course, home of the Master’s tournament.

“Maybe this event gets people to think about alternatives, different crucibles, different ways to make silicon.”

The high-silicon, low-contaminant nature of Spruce Pine quartz makes it integral to advanced chip manufacturing, where even an atomic quantity of impurity can jam up the circuitry etched into a semiconductor. The chips themselves aren’t actually made of quartz. High-purity quartz crucibles are used to melt down polysilicon, the pure silicon needed to make computer chips and solar panels.

The crucibles only last a few weeks before they need to be replaced, and the need for advanced chips is increasing at a breakneck pace. A surge in AI-powered devices is expected to increase global demand for advanced chips by at least 30 percent by 2026, according to a recent Bain report that warned of an imminent shortage.

By some estimates, Spruce Pine accounted for 70 percent of the high-purity quartz needed to produce the pure silicon used to make most advanced chips, including those needed for AI. On top of that, a single company in Taiwan, TSMC, manufactures the majority of those chips. And now, the disaster in Spruce Pine is drawing attention to how fragile the global chip supply chain already is.

“Maybe this event gets people to think about alternatives, different crucibles, different ways to make silicon,” said Dustin Mulvaney, an environmental studies professor at San Jose State University who studies solar cell supply chains.

We don’t yet know how bad the damage is at the Spruce Pine mining facilities. The two companies that own most of the quartz mines, Sibelco and the Quartz Corp, both halted production on September 26, as the storm was moving through western North Carolina. Images of Spruce Pine show the downtown completely flooded and buildings washed out near the rail lines that connect the mines to the rest of the world.

Sibelco said in a statement that it was “actively collaborating with government agencies and third-party rescue and recovery operations to mitigate the impact of this event and to resume operations as soon as possible.” The Quartz Corp is similarly assessing the situation at its three mines in the area as well as the infrastructure around them, and “its US plants are stopped for an unknown duration,” the company’s spokesperson May Kristin Haugen said in an email.

As for how much this will upend the global chip supply chain, well, we’ll have to wait and see.

Even with the Spruce Pine mines offline, chipmakers should have stockpiles of polysilicon or the ultra-pure quartz they need to make it available for some amount of time. And if they run out of the Spruce Pine quartz, there are other sources of quartz in places like China and India that are viable but not as high quality or cost effective.

And, perhaps anticipating some future disaster, the mining companies in Spruce Pine don’t keep all their high-purity quartz on site. “Between our own safety stocks, which are built in different locations, and the ones down in the value chain, we are not concerned about shortages in the short or medium term,” said Haugen, who cited the pandemic as a teaching moment in supply chain resiliency.

What we might expect, however, is prices of some electronics to rise. If there’s not enough Spruce Pine quartz to go around, especially in the long term, the industry will have to come up with alternative sources of high-purity quartz. The methods for refining those minerals elsewhere are more resource intensive and potentially carry a heavier carbon footprint because the quartz used as a raw material doesn’t start out as pure as the quartz from Spruce Pine. As one expert told Wired magazine, the climate-fueled flooding in western North Carolina could lead to more negative consequences for the climate, contributing to more disasters in the future.

To many casual technology users, this all comes as a surprise. After all, we’re used to thinking about chips being designed in Silicon Valley and then made in Taiwan. Of course these places aren’t safe from shocks—earthquakes and wildfires are a threat in Southern California and Taiwan is prone to earthquakes and landslides. We don’t often think about the many raw materials needed to fill the supply chain and the globalized economy’s habit of always seeking out the cheapest available option, even if it comes from a single small town in the Blue Ridge Mountains that happens to be prone to floods.

“We just don’t pay much attention, or as much attention as we should, to the underbelly of our economy,” said Conway. “And this is part of the underbelly.”