Ricky Fitchett/ZUMA

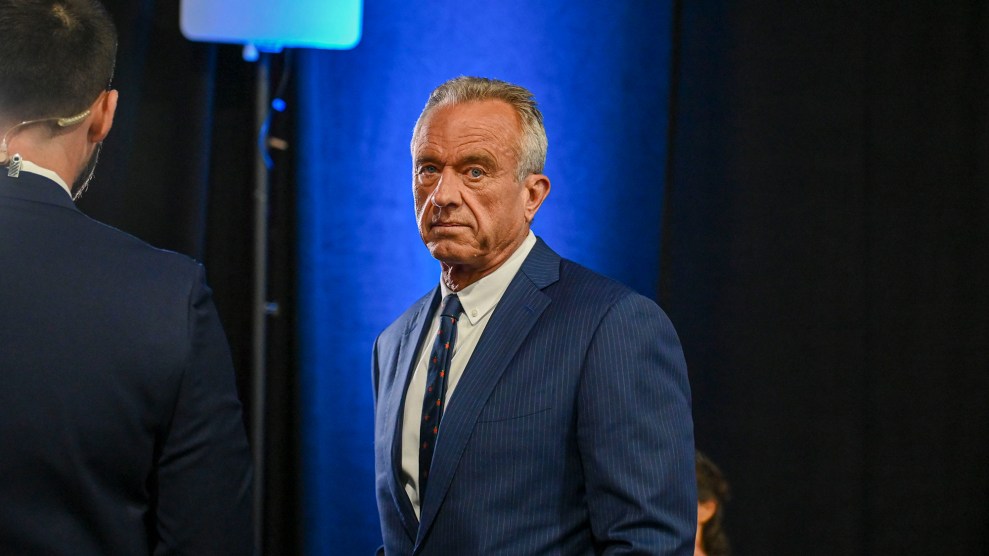

By the time he endorsed former President Donald Trump in late August, Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s independent presidential bid had long ceased to be a functioning campaign. He had collapsed in the polls, failed to qualify for the ballot in many states, and basically stopped doing events.

Yet, in death, his campaign found new life—as a way to game the democratic process for his favored candidate.

In other words, North Carolina chose to ignore its own law in order to ensure that a guy who was only ever running as a gimmick could pull one last stunt.

After dropping out, Kennedy sued to be removed from the ballot in deep red states, and swing states such as Michigan and Wisconsin, where his presence might take votes away from Trump. But he fought to stay on the ballot in blue states. He continued to encourage people in those places to vote for him for a time, even though he was endorsing Trump. In New York, Kennedy sued to be put back on the ballot. When his effort there was unsuccessful, he appealed to the US Supreme Court—which ruled against him.

One state was happy to accommodate RFK Jr.’s bit of gamesmanship. In North Carolina, a lower court removed Kennedy from the ballot in early September, only for the notoriously partisan North Carolina Supreme Court to step in to “protect voters’ fundamental right to vote their conscience and have that vote count.” The high court ordered the State Board of Elections to restore Kennedy to the ballot. But ballots were already printed. There was also the matter of state law: Early voting by absentee ballot was scheduled to begin on September 6.

As Mark Joseph Stern explained at Slate, Kennedy had announced that he was suspending his campaign a day after the state’s deadline for removing a candidate from the ballot and only submitted a request to get off the ballot five days after the Trump endorsement. He acted with all the tact and urgency of a man with a dead bear cub in his trunk.

In other words, North Carolina chose to ignore its own law in order to ensure that a guy who was only ever running as a gimmick could pull one last stunt. It lost two full weeks of early voting because the state supreme court found a special Kennedy Clause in its constitution.

Finally, after a fairly heroic effort by state and county workers, ballots were set to start being mailed out to in-state voters on September 24. Then, just as the window opened again, Hurricane Helene slammed it shut again.

The storm, which smashed through Florida and southern Appalachia this weekend, caused catastrophic destruction which affected communities are only beginning to take stock of. It washed out roads, knocked out power, killed at least 130 people, and flooded scores of communities. And with that immediate hit, came a number of logistical ripple effects.

Importantly, the US Postal Service announced that it was suspending operations in a number of North Carolina zip codes, and temporarily shuttering post offices in 39 Western North Carolina communities. In the immediate term, that means that people in those areas will have difficulty sending and receiving mail, and the USPS will have difficulty processing it. It is hard enough to simply move around.

As Gerry Cohen, a member of the elections board in Wake County (which includes the capital, Raleigh) explained on X, any long-term complications with the delivery and mailing of absentee ballots because of Helene could have an impact well outside the storm’s footprint. Residents who have temporarily relocated, or been displaced, or are simply attending college in a different part of the state, for instance, might be counting on a home county in the affected area to mail them an absentee ballot.

It is not a good idea, while people are struggling to access water and other basic supplies, to try to game out what something actually means for the election. (It is mostly a pointless exercise even when they aren’t.) Although absentee voting surged during the pandemic election of 2020, it fell off in 2022 and residents do not rely on mail ballots the way people in, say, Arizona do. But it goes without saying that weeks of delays in violation of state statutes, followed by a once-in-a-century storm, will have simply made things logistically harder for people than they otherwise would have been or should have.

Residents will have a far shorter window for early voting than they were supposed to have—and that the law says they should have—because of RFK and the state supreme court. That window will now get even shorter because of the storm. Acts of God may be unavoidable, but shameless acts of partisanship are perhaps not.