Rex and Ruby Thacher prepare to evacuate from the path of Hurricane Milton with their dogs.Stephen M. Dowell/Orlando Sentinel/ZUMA Press Wire

This story was originally published by the Guardian and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

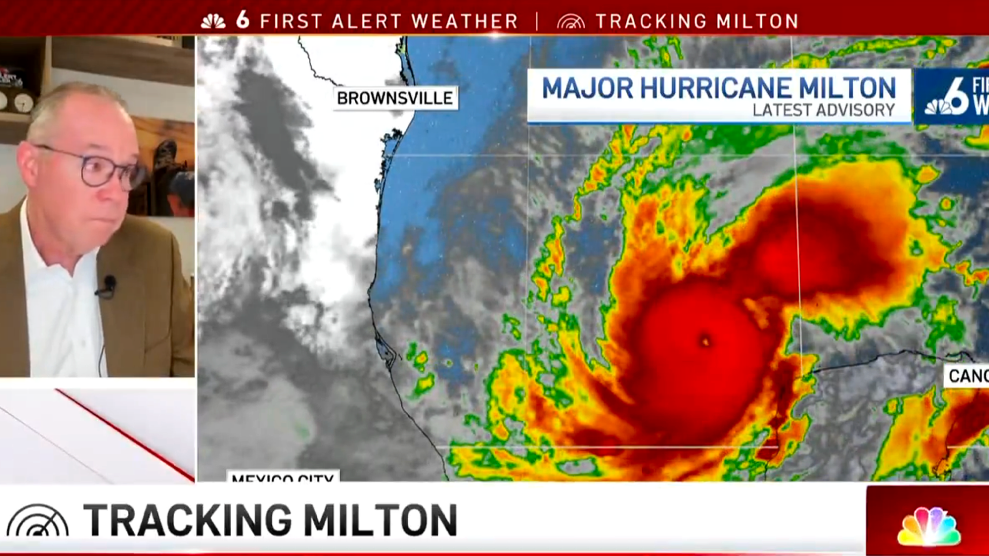

On October 7, as Hurricane Milton was just days away from making landfall in Tampa, Florida, the city’s mayor, Jane Castor, issued a dire warning to residents in evacuation zones: “If you choose to stay…you are going to die.”

But leaving one’s home to avoid the Category 5 hurricane is not possible for everyone.

When people don’t flee their homes due to weather crises, despite warnings from government officials, there are typically two reasons why, according to Cara Cuite, an assistant professor in Rutgers University’s department of human ecology. They either don’t believe they’re at risk or that the risk is overblown, or there are situational or structural elements that prevent them from doing so.

In the case of Hurricane Milton, which was set make landfall near Tampa Bay on Wednesday evening, Cuite said the former group is probably pretty small, as Castor and other trusted officials have been unequivocal about the dire consequences of staying. But for the second group, here’s what they might be up against:

The Cost of Travel

A 2023 estimate by the Federal Reserve indicated that nearly 40 percent of Americans couldn’t cover a $400 emergency expense in cash, and a 2021 study found that people who evacuated from the Texas Coastal Bend during Hurricane Harvey spent about $1,200 on average on evacuating—more if they had to stay in hotels.

To evacuate via personal car, residents need to be able to pay for gas, a hotel, food and any other relevant necessities, assuming their car is in workable condition. If they evacuate via plane, they would need to pay for the aforementioned costs, along with the cost of a plane ticket, assuming they can reach an airport. Though some airlines were accused of price-gouging as people attempted to flee Florida, others say that they have since capped their prices.

Cierra Chenier, a writer and historian from New Orleans, said that inequalities were only exacerbated by emergency situations. “Any socioeconomic disparity that exists on a day-to-day is only going to be heightened during disaster,” she said. “It’s always those, the communities that are most vulnerable, that suffer the most.”

Before Hurricane Milton, the Florida department of health deployed nearly 600 emergency response vehicles to support evacuations, while the Florida division of emergency management is also offering free evacuation shuttles to shelters. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) is currently providing some financial relief to victims of Hurricane Helene, the category 4 storm that ended on September 27 and killed more than 225 people throughout Florida, Georgia, and the Carolinas. But everyone who needs help may not receive it in a timely manner, or at all.

Nowhere to Go

Many of the shelters, hotels and rentals that people in Florida would typically flee to are already full because of Hurricane Helene.

Stacy Willet, a professor in emergency management and homeland security at the University of Akron, said that a lack of pre-established places to evacuate can prevent people from leaving.

“Evacuation by invitation is one of the strongest ways to get people to leave,” she said. “If they have a place to go, if they know that they have a house in a safe zone—just sometimes knowing and offering that place to that person in that disaster zone is enough to get them to move earlier.”

But some people have to figure out accommodations without having the support network of family or friends. If shelters within a reasonable distance are packed and hotels are full, those people must either travel extreme distances or simply try to ride out the storm.

Disability

For people who are able-bodied, the specific needs of disabled or ill people during evacuations may not be front of mind. But a disability or illness may prevent someone from being able to leave their homes, much less travel elsewhere.

“If you have a disability and you don’t have an accessible place to evacuate to or you don’t have a vehicle, that’s extra difficult,” Cuite said. “You have to find help moving that can actually accommodate, let’s say, a wheelchair or whatever you might need for your disability. So these things can compound on each other when you fall into multiple categories.”

Pets

Some shelters are not pet-friendly and those that are may have a cap on the number or types of pets they accept, so many people will stay behind and avoid evacuation to care for their pets.

“Sometimes people stay to protect their home, to protect their animals that they can’t take with them,” Cuite said. “In more rural areas maybe not pets, but farm animals. People feel responsible for staying behind to take care of things and their animals that they’re in charge of.”

Fear of permanent displacement

An estimated 1.5 million people evacuated Louisiana before Hurricane Katrina, but many of those people were unable to return. For some, especially those who have experienced natural disaster caused displacement before, the fear of leaving and either not being able to return or returning to nothing is enough to attempt surviving a hurricane by staying put.

“It’s great that you might have busloads of people that you’re able to get out very quickly, but who knows how they make it separated from their families, which we know happens. How long are they going to be gone? We don’t know what the impacts are gonna be from these different storms,” Chenier said. “And so what is the strategy around ensuring that people have a right to their homes and have a right to return?”