40 Acres and a Lie tells the history of an often-misunderstood government program that gave formerly enslaved people land titles, only to take the land back. Read more here and listen to a three-part audio investigation here.

Ruth Wilson squinted through her browline glasses at the image of a smudged, crumpled document on the computer screen.

“To all whom it may concern,” she read. “Fergus Wilson having selected 40 acres of land on Sapelo Island, Georgia, pursuant to Special Field Orders, No. 15…has permission to hold and occupy said tract…”

The 71-year-old retired high school counselor let out a deep exhale as she leaned back on her leather living room couch, her dog Luckie looking up from his cushion by the fireplace. “Sometimes things aren’t worth the paper they’re written on,” she remarked. “They took it back.”

The document was one of 143 land titles contained within recently digitized records of the Freedmen’s Bureau, the federal agency tasked with, among other things, distributing land to those who had been emancipated from slavery. These titles detail specific Black men and women who received plots of land in Georgia and South Carolina and empowered the Center for Public Integrity to conduct the first-ever effort to identify and locate living descendants of those whose land was stripped away as Reconstruction faltered. To date, reporters have traced genealogies for roughly 100 of the 1,250 identified as having received land following the orders. While many of their descendants stayed in Georgia and South Carolina, others migrated to states like Delaware, Michigan, and Ohio.

Among the land titles was the crumbling slip of paper—with smudged ink, torn edges, and three deep creases suggesting it had been folded into a small square—that in 1865 granted Wilson’s great-great-grandfather Fergus Wilson his 40-acre plot.

When an English professor at the University of South Carolina, Michele Reese, first contacted Ruth Wilson and told her that one of her ancestors was given land by the Freedmen’s Bureau, she had a hard time believing it. To her, 40 Acres and a Mule had always invoked little more than one in a long series of hollow, broken promises.

“In the Black community,” she explained, “we don’t say it, but we understand we don’t plan on the white man for nothing.”

Fergus Wilson had been enslaved by Charles Spalding, whose family owned a sugarcane and cotton empire on Sapelo Island, Georgia. As the biggest landowners on the island, the Spalding family enslaved 385 people there. In 1861, they sold Wilson to the president of a railway company, and he was detailed to a railway hospital in Savannah. In court documents he’d file years later, Wilson said he and his wife, Priscilla, would sneak baskets of food to Union prisoners in rail cars during the war. “I had rather suffer death than to see them open their mouths and we not fill them,” Wilson wrote, before adding that the Union troops later stole all the crops from his garden.

“He had a great quantity of rice, but I don’t know how much. I can’t count, but my old man, he can count,” Priscilla would testify years later. “I saw them take the rice in bags, they took it away on their shoulders. It was good, clean rice.”

Under General William T. Sherman’s Special Field Orders, No. 15, formerly enslaved men and women were entitled to up to 40 acres. For his plot, Wilson chose land south of Savannah on Sapelo Island, on a rice plantation that had been previously owned by the Spaldings. The eldest of his five sons, Fergus Jr. and Richard, also received titles to 40 acres each on Sapelo Island.

But once the war ended, the Spaldings fought to get their land back. Charles Spalding, who served as a lieutenant colonel in the Confederate Army, swore his allegiance to the Union and sought a presidential pardon in December 1865.

A month later, an administrator for the estate of his deceased brother Randolph asked the Freedmen’s Bureau to return the Spalding plantation to their family so they could pay off creditors. His widow and their children had all taken the amnesty oath, according to a letter sent to county officials, and needed those 7,400 acres to pay the family’s debts.

President Andrew Johnson soon pardoned Charles Thomas Spalding, allowing him to reclaim the Sapelo Island plantation as his own. While the Freedmen’s Bureau resisted returning land to Confederate planters like Spalding, by 1867 the plantation had been returned to him and Wilson’s land title rendered worthless. Wilson’s sons Fergus Jr. and Richard would eventually leave Sapelo Island and move to Savannah after losing their 40 acres too.

Instead of moving back to Savannah, Wilson pooled his money with other freedmen to buy farmland in Camden County, near the coastal border with Florida, according to research conducted by professor Reese, of the University of South Carolina. They paid half upfront—$300—to a Freedmen’s Bureau agent, then paid off the rest after selling their first harvest.

Before he died in 1873, at about 70 years old, Wilson successfully petitioned the Southern Claims Commission for half of the $492 he requested as restitution for the crops and rice that Sherman’s soldiers stole from him. Years after Fergus’ death, his sons Hercules and Anthony Wilson would serve in the Georgia General Assembly.

“Of the three colored members in the House two are brothers. They are Hercules Wilson, of McIntosh, and Anthony Wilson, of Camden,” relayed an October 1885 article in the Savannah Morning News. “Wilson, of McIntosh, is a brick mason, and Wilson, of Camden, is a farmer and school teacher,” the report continued. “All are well-to-do, industrious, and sober. They board together at a private house on Peters street.”

That year, Hercules Wilson proposed a civil rights bill that would have banned racial discrimination by private businesses such as hotels and theaters, earning a rebuke from the most widely read newspaper columnist in the South. “I see that the colored member from Camden has introduced a bill to enforce the perfect equality of the races,” columnist Bill Arp wrote in a front-page Atlanta Constitution piece in which he implored state lawmakers to not be like others before them who had “pandered to northern prejudices” and “were afraid to do anything for fear the north would be offended.”

“Our lawmakers will set down on Camden & Co. Our people have got as good manners and as much humanity as any people and know how to treat the negro according to his disservings,” Arp continued. “We intend to make distinctions. The Creator made them and drew the color line and we shall not try to wipe it out…If the wards are dissatisfied, let them go elsewhere and get another guardian.”

By November 1885, Hercules Wilson had resigned, noting that he was better paid as a bricklayer than as a lawmaker. It would be more than a century before Georgia’s public accommodations were desegregated.

“If anything were wanting to show the inferiority of the colored race, it is exhibited in the person of Hercules Wilson,” declared the Boston Evening Transcript. “Had he been a white man, he would have joined the third house of the Legislature. But the poor noodle preferred to lay bricks at $4 or $5 a day!”

His great-granddaughter Ruth Wilson has only ever been to Georgia once, when as a child she was taken to a wedding in Savannah. She spent her entire life in North Carolina, where her grandfather, Hercules Wilson Jr.—born in 1882—settled to attend seminary, becoming the first in the family to receive higher education. “My granddaddy left Georgia,” she said. “And no, he didn’t go back.”

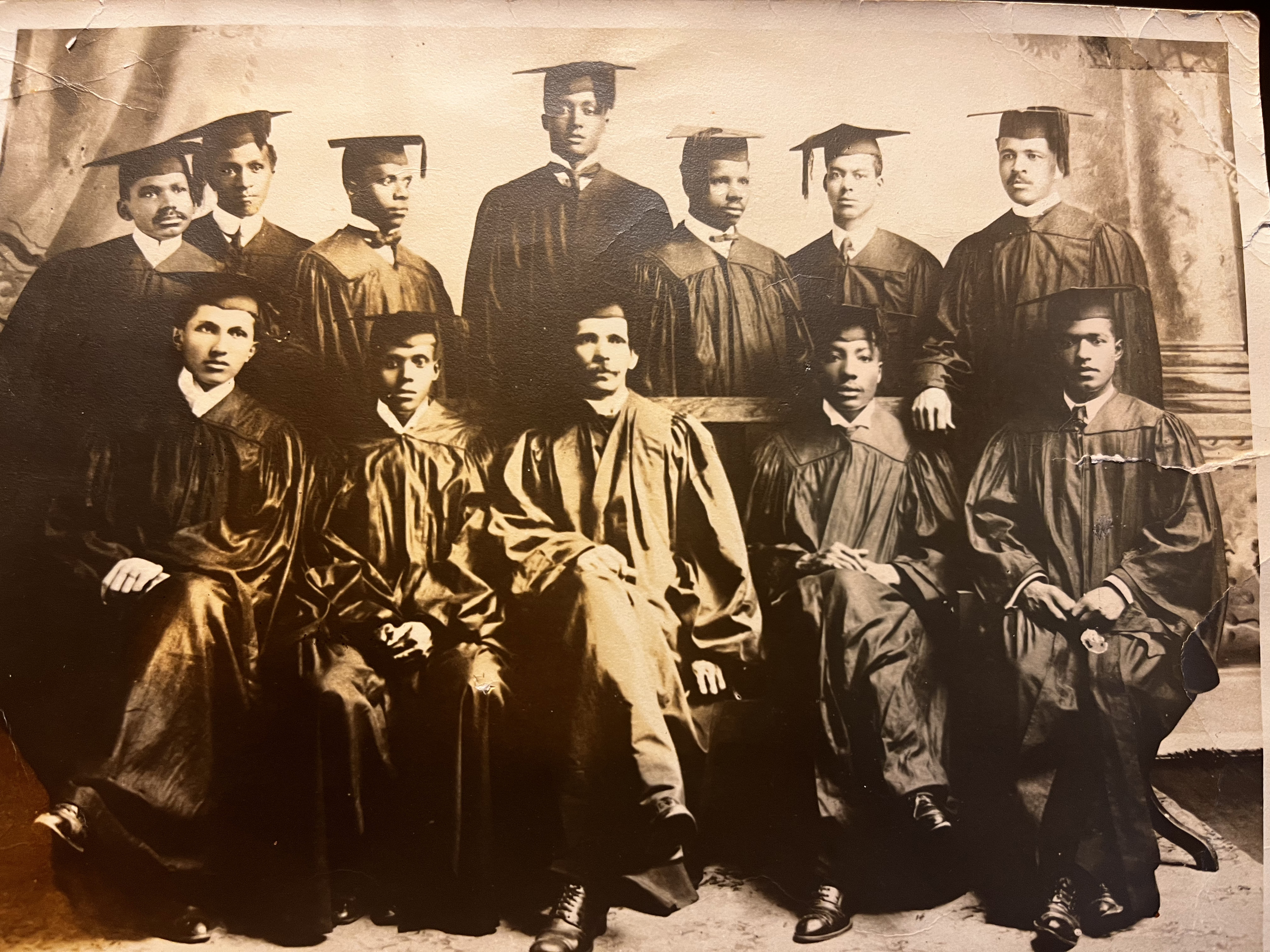

Hercules Wilson Jr. is seated in the front row, second from the right.Courtesy Ruth Wilson

She grew up knowing relatively little about the family down in Georgia. Her grandfather told her that his father had been a state legislator, but other than that they never discussed slavery and Reconstruction. Hercules Wilson Jr. married and began pastoring in a series of churches near Charlotte. He was proud that all three of his children would go on to college. He loved reading the classics, Ruth recalled, and watching his family members dance. As a teen, he got his family kicked out of a Baptist congregation by dancing at a church picnic. The Wilsons have been Presbyterians ever since.

Ruth was raised in Henderson, North Carolina, the only child of Hercules’ son James and his wife, Mary, who were both teachers. She still recalls her parents, after a trip to Winston Salem, bringing back the first black doll she’d ever seen—one she still has to this day—and a white-owned pharmacy where a young white girl was allowed to sit at the counter to eat ice cream but she was not. “If you grow up in it, nobody has to tell you about skin color,” Ruth said. “It comes naturally.” She attended elementary and middle school amid the tumultuous efforts at integration that followed the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision before enrolling in a private high school and then the University of North Carolina, Greensboro.

It was only in recent years, after beginning to use Ancestry.com to trace her genealogy, that she first heard the name Fergus Wilson and learned that he’d been given 40 acres only to have them taken away.

“Nothing is like manna from heaven. And if it’s gifted to us, beware: cuz what is given can be taken back,” Wilson said. “And the good news about [Fergus], he was smart enough to have a Plan B.”

This project is a collaboration between the Center for Public Integrity, the Center for Investigative Reporting, and the Investigative Reporting Workshop. Read more here.

Top illustration: Michael Johnson: Source images: Courtesy Ruth Wilson; Federico Respini/Unsplash; National Archives; Freedmen’s Bureau Records