Bettmann/Getty

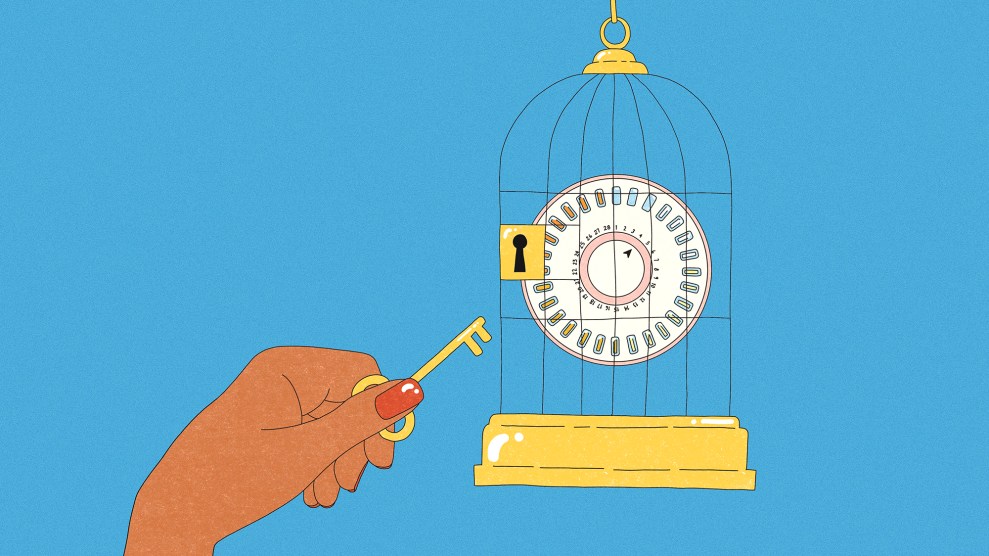

Last July, in a win for reproductive justice advocates, the Food and Drug Administration approved the first over-the-counter birth control pill. This week, the progestin-only pill, Opill, shipped to retailers like CVS and Walgreens. It’s expected to be available for purchase before the end of the month, at a price point of $20 per one-month supply or $50 for three months.

It’s difficult to underscore just how big a deal this is. For the first time since oral contraception was approved in 1960, it may mean an end to many of the difficulties that come with a doctor’s visit for the medication—taking time off of work, securing child care, paying appointment copays, and more—that particularly burden people of color, those who are disabled, young, or live in rural areas. As California Latinas for Reproductive Justice Communications Director Susy Chávez Herrera told me in 2022, an FDA approval would mark a “step forward in terms of expanding health care access, and folks in our community having bodily autonomy.”

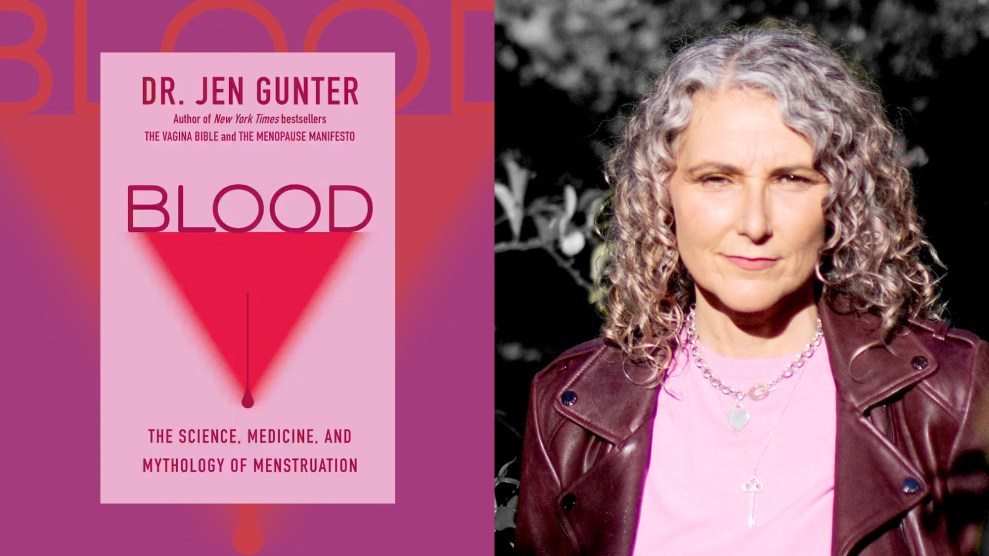

To better understand the historical significance of an over-the-counter birth control option, I called Elaine Tyler May, a historian at the University of Minnesota and author of the 2010 book America and the Pill: A History of Promise, Peril, and Liberation. (As chance would have it, she was also a participant in some of the first trials for low-dose birth control pills.) In our nearly hour-long conversation, which happened ahead of the FDA’s decision, we covered a lot of ground, including how the Pill changed American sex lives and her own family’s history in helping people access contraception.

Now that the Pill is arriving in drugstores, I wanted to revisit our wide-ranging interview. You can read an edited and condensed version below:

Take me back to the 1960s. What did it look like when the Pill was made available? How did that change things for American women?

The Pill gave women power over birth control. A woman could control it without the participation of her sexual partner and without necessarily even his knowledge. That was a big change. It released women from needing a doctor’s assistance. You didn’t have to have a doctor fit you for a diaphragm. They needed a prescription, yes, but they didn’t need a doctor.

The Pill shifted control to women, but without the feminist movement, the Pill wouldn’t have really done anything to change women’s lives. Science doesn’t create social change. Innovations are not what drive social developments. It’s the reverse. The scientific and medical community has been active, of course, in developing various methods of contraception. But it’s really social and political activism that has made contraception and abortion life-changing for women. The Pill just enabled women to pursue their aspirations without being terrified that any minute they could get pregnant.

Say I’m a wife in the 1960s, and I wanted to get on the Pill. What steps would I have to take?

Well, it depends on where you live. The pill was not legal, even if prescribed by a doctor, in many states. That changed because women agitated for it. And one by one, states fell into line.

I was surprised to learn, reading your book, what hopes people had about the Pill—in combating overpopulation, poverty, even communism. What was the thought there?

The pill came out around the peak of the Cold War. And so a lot of its promoters were saying, Look, this is one more tool in our arsenal against communism. Because in developing countries, they thought, overpopulation was a crisis, it was causing poverty and hunger. And they thought, If we can just go in there with birth control pills, then it will alleviate a lot of the suffering that leads some of these folks to be drawn to communism. It was a way in which the so-called free world tried to blunt the potential for overpopulation to [lead to] communism.

In your book, you share that your parents played a role in helping people access the Pill in the early days after it was first approved. Can you tell me a little more about that?

My father was a physician in the field of reproductive medicine. His private practice was an infertility clinic. So people who, for one reason or another, were not able to get pregnant, would come to his clinic for treatment. My mother helped found a few Planned Parenthood clinics in Los Angeles, and my father served as the medical director.

My father was very interested in the science of it. People would ask him, “How come on the one hand, you’re trying to help people get pregnant, and on the other hand, you’re trying to help people not get pregnant?” And his motto was, “Every child should be a wanted child.” People who want children should be able to have every benefit of medical science to help them, and same thing for the people who don’t want children. People should determine their own reproductive goals. That was how he saw it.

What do you think your parents would think about the Pill being made available over the counter if they were still with us today?

It’s hard for me to know. But I’m guessing that if the Pill was shown to be effective and safe without [a doctor] follow-up, then I think they would be for it.

Are there any parallels that you’ve seen between the reproductive justice movement of the past and today?

Through most of the 19th century, abortion wasn’t a crime. Abortion was simply the most effective means of birth control, and it was widely practiced. In the late 19th century, when doctors started to develop medical schools, you began to see a shift in power dynamics in the medical profession, and men wanting to be the gatekeepers.

This is also the time when childbirth moved from mostly at home to mostly in hospitals. And again, doctors wanted to take control away from women and mothers and families by shifting childbirth to hospitals, which was initially a very dangerous thing: More women died when they were hospitalized because of [greater exposure to] germs. I know when I had my first child more than 50 years ago—yikes—fathers were only just beginning to be allowed into labor and delivery rooms. All of these practices around reproduction and birth, they’ve changed so dramatically over the years.

I don’t know where we’re headed. I’m just baffled by seeing things happening that I never, ever imagined I would see happening, like the overturning of Roe. Things that seemed to be resolved half a century ago, coming back into public policy debates. It’s just shocking to me. It’s like, Oh, my god, are we in a time machine going backward? What’s happening here?