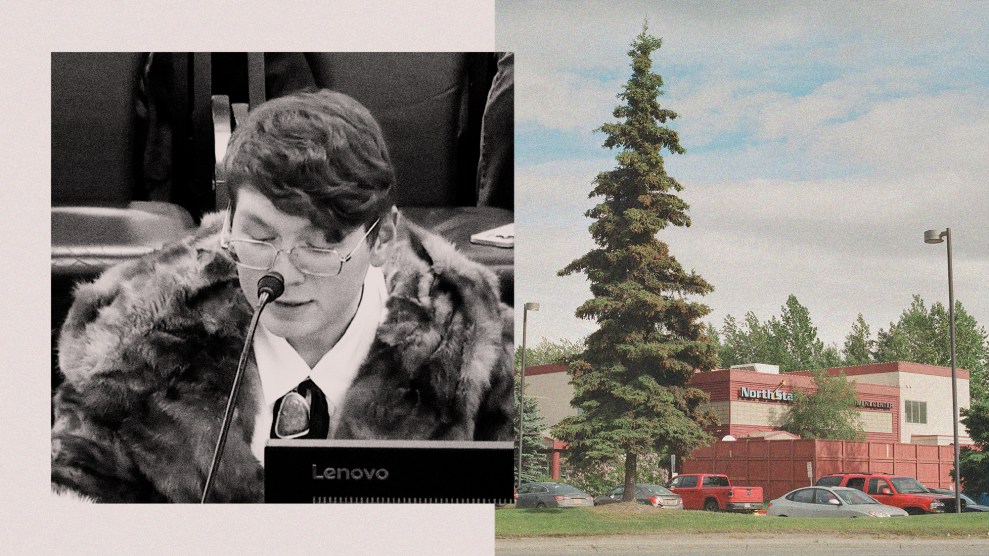

Mateo Jaime, who spent two months at a psychiatric hospital as a foster child, speaks at an Alaskan legislative hearing Thursday.Mother Jones illustration; Alaska State Legislature; Ash Adams

It was 2018 when Mateo Jaime was admitted to North Star Behavioral Health, a psychiatric hospital in Anchorage, Alaska. He didn’t need acute psychiatric care, he says. Rather, Jaime was a teenager in the foster system, and Alaska’s Office of Children’s Services didn’t have a foster home for him. Jaime would spend two months at the facility, during which time he was held in seclusion and witnessed the forcible injection and physical restraint of other patients. He still has PTSD from the experience.

Jaime wasn’t alone. A yearlong Mother Jones investigation found that foster kids have been admitted hundreds of times to North Star, where some spend months or even years. Despite the facility’s troubling track record of assaults, escapes, and improper use of seclusion, state officials have admitted what foster youth have long suspected: Foster children are warehoused at North Star when there’s nowhere else for them to go.

Now, two bills introduced in the state legislature aim to reform psychiatric treatment for vulnerable youth in Alaska. Though neither bill mentions North Star by name, it looms large as the state’s only private psychiatric hospital for children.

HB 363 would require a court to review a foster child’s placement at a psychiatric hospital within 72 hours to determine if that child meets medical criteria for hospitalization. (There’s no statute on when an initial hearing should take place, though a preliminary injunction requires a hearing within 30 days.)

Jaime was among those who testified at an emotional hearing on Thursday. “I felt like a zombie for two months,” he said. “I had no control and no voice over the situation.”

Rep. Andrew Gray, the Anchorage Democrat who sponsored the legislation, said he expected that courts and child welfare officials would push back on the proposed 72-hour timeline for scheduling reasons. “Our priority should not be to make this process more convenient for the adults involved,” he said. “Being admitted to a psychiatric facility is a form of incarceration.” Gray told Mother Jones the proposed legislation was inspired by our reporting, as well as his own experience as a foster parent.

A second bill, HB 366, would require health department employees to conduct unannounced visits to residential psychiatric facilities at least twice a year, and to interview at least half of the patients during such visits. It would also require facility staff to report incidents of seclusion or restraint to the state within a day of the incident, and allow weekly, confidential video visits with parents or guardians. Rep. Maxine Dibert, a Fairbanks Democrat and the legislature’s sole female Alaska Native lawmaker, was reportedly inspired to introduce the bill by the prevalence of Native children in psychiatric residential treatment facilities. (The same legislation was also introduced in the Senate.)

Both bills have relatively slim chances of passing this year, with just two months left of the legislative session.

For years, Alaskan advocates have expressed concern about the unnecessary hospitalization of foster children at psychiatric facilities. In February, after learning about a 14-year-old foster child who was hospitalized for 46 days before a hearing, Alaska’s Supreme Court concluded, “There is no doubt that children in OCS custody are at substantial risk of being hospitalized for longer than they need, or when they do not need to be hospitalized at all.”

Universal Health Services, the Fortune 500 company that owns North Star, has consistently denied wrongdoing, but it didn’t immediately respond to request for comment on the legislation. The Anchorage Daily News recently reported, however, that North Star paid a lobbyist $41,000 to advocate this legislative session on “issues related to mental health, workforce, background checks and State of Alaska budget.”