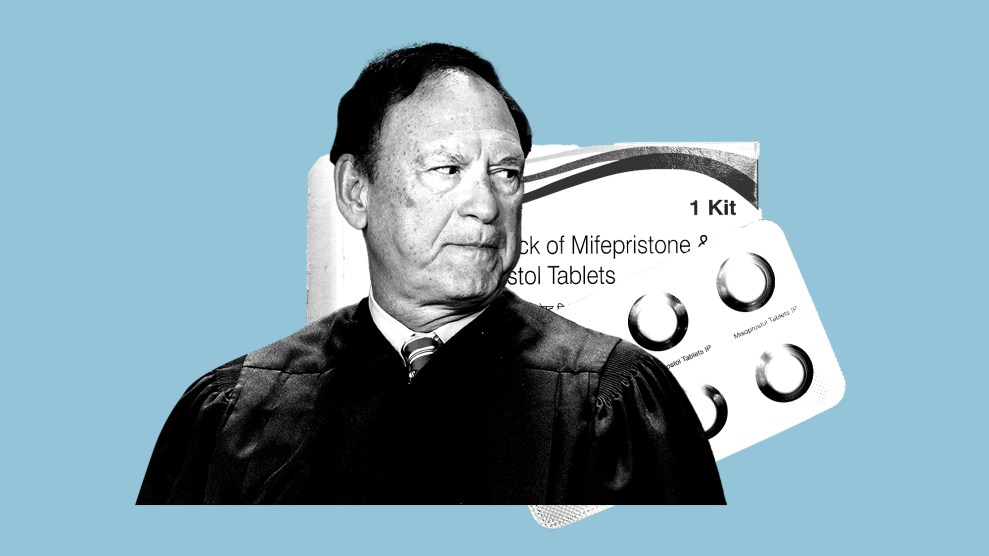

Mother Jones illustration; Eric Lee/CNP/ZUMA; Soumyabrata Roy/NurPhoto/ZUMA

Justice Samuel Alito implied that mifepristone—one of the two drugs used in medication abortion, which the Supreme Court will decide whether or not to restrict in what has been billed as “the biggest abortion case since Dobbs“—may cause “very serious harm.”

But there’s just one problem: more than 100 scientific studies show that abortion pills are safe and effective, as my colleagues and I have reported.

Alito made the comments this morning during oral arguments in FDA v. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine. In 2000, the Food and Drug Administration approved mifepristone. The drug was made more widely available in 2016, when the FDA allowed it to be used through 10 weeks’ gestation rather than 7 weeks’ gestation; in 2021, the agency relaxed additional rules around how it could be prescribed, including allowing it to be given virtually. The stakes of the case are significant, given that medication abortion accounts for more than half of all abortions nationwide, according to the Guttmacher Institute, and that telehealth abortions—in which providers virtually prescribe and mail pills—continue to rise, even in banned states.

In questioning today, Alito prodded at the FDA’s regulation of mifepristone by trying to explore the possibility that despite years of safety, there were hidden adverse effects not being tracked.

“Has the FDA ever approved a drug and then pulled it after experience showed that it had a lot of really serious, adverse consequences?” Alito asked Jessica Ellsworth, the lawyer representing Danco Laboratories, a manufacturer of mifepristone.

Ellsworth said yes, noting that the FDA collects data on the impacts of the drugs it approves.

“Don’t you think the FDA should’ve continued to require reporting of non-fatal consequences?” Alito continued, referring to the FDA’s 2016 decision that prescribers didn’t need to report adverse events from mifepristone because of the drug’s safety record. As Ellsworth told Alito, the FDA made that decision “based on more than 15 years of a well-established safety profile when that reporting was required.”

Alito, though, remained undeterred. “So why would that be a bad thing? You don’t want to sell a product that causes very serious harm to the people that take your product, relying on your tests and the FDA’s tests—wouldn’t you want that data?”

This idea that there is some secret data not being harvested ignores all the clear data we do have showing that mifepristone is safe.

Study after study has shown that the drug does not, in fact, produce “a lot of really serious, adverse consequences.” The FDA, and other large studies, have reported low rates of serious adverse events. And research published in February—which I reported on at the time—showed that medication abortion is not only safe, but just as safe when it’s prescribed virtually as in person.

Alito’s line of questioning comes after two research papers claimed to show the dangers of mifepristone and were cited in the Texas court ruling that led to the Supreme Court case. But both of those reports have since been retracted after an independent peer review uncovered unsupported conclusions due to flaws with the study design, methodology, and data analysis—along with possible conflicts of interest given the lead author’s affiliation with the Charlotte Lozier Institute, an anti-abortion advocacy organization.

Ellsworth addressed the retracted studies this morning after Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson asked her if the company had “concerns about judges parsing medical and scientific studies.”

Referring to the retracted studies, Ellsworth replied: “Those sorts of errors can infect judicial analyses precisely because judges are not experts in statistics, they are not experts in the methodology used in scientific studies, for clinical trials. That is why FDA has many hundreds of pages of analysis in the record of what the scientific data showed, and courts are just not in a position to parse through and second-guess that.”

Whether the justices humble themselves accordingly, though, remains to be seen: their decision in the case is expected by the end of June.

Correction, March 27: This post has been revised to correct the year the FDA allowed mifeprestone to be used through 10 weeks’ gestation.