17 January 2024: In the cell laboratory, culture dishes are prepared at the Fertility Center Berlin to collect the eggs after egg retrieval. Jens Kalaene/Getty Images

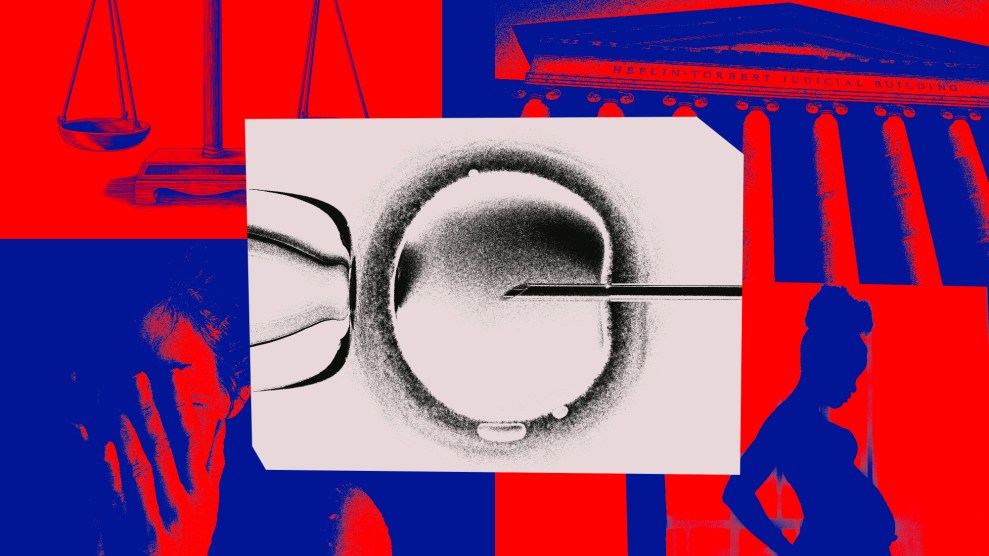

In a landmark ruling last week, Alabama’s Supreme Court declared that embryos created through in vitro fertilization were children, and therefore subject to the state’s abortion ban. The effects of the ruling are already apparent: Three IVF clinics have paused their services, and it’s unclear whether patients in the state will be able to decide the fate of their frozen embryos.

The decision spurred a raft of outraged coverage. In an op-ed, the LA Times called it “breathtakingly arrogant, slapdash and pernicious.” The Washington Post‘s Ruth Marcus began her column, “Welcome to the theocracy.” In a New York Times op-ed, political pollster Kristen Soltis Anderson wrote, “As a result of the recent Alabama Supreme Court decision…the hope and miracles that I was blessed to experience are at risk for families whose clinics have suspended treatments.”

To many, the basic premise underlying the Alabama decision seemed contradictory: Don’t anti-abortion activists want people to have more babies? In theory, yes—yet paradoxically, the ruling was the result of a decades-long crusade against fertility treatments mounted by the same people who oppose access to abortion.

Much of the current furor over fertility treatments stems from a 1987 Vatican teaching of the Catholic church, which prohibited Catholics from using the then-nascent technique of IVF. “The practice of keeping alive human embryos in vivo or in vitro for experimental or commercial purposes is totally opposed to human dignity,” the Vatican officials wrote. In particular, the guidance objected to the creation of extra embryos that could wind up being discarded—a common practice in IVF, because of the inherent inefficiency of human reproduction: Many embryos aren’t viable, so the more that are available, the greater the chances for a successful pregnancy.

In the years since that declaration, assisted reproduction technology both advanced and became more popular; today about 2 percent of babies are born via IVF. Meanwhile, Catholic doctors began to market what they believed were morally acceptable “alternatives.” One of them was Thomas Hilgers, who developed a practice called NaProTechnology, which promises success rates better than those of IVF to women who track their periods and in some cases take medication and undergo surgery. As I have reported, there is no robust evidence backing Hilgers’ method, yet Catholic hospitals and medical groups continue to promote it.

Around the same time that Hilgers was building his NaProTechnology practice, anti-abortion activists set their sights on the extra embryos that remain frozen after IVF patients complete their families. In 1997, Ron Stoddart, the head of a Christian adoption agency called Nightlight, founded Snowflakes, a group that matched unused frozen embryos with families wanting children. Beginning in 2002, Snowflakes received funding from President George W. Bush’s Department of Health and Human Services as part of the federal government’s Embryo Adoption Awareness Campaign; though that program was halted in 2013, it was restarted under the Trump Administration and now gives out $1 million in grants every year to several embryo adoption agencies.

Members of mainstream Protestant churches haven’t always agreed with Catholics that assisted reproduction is morally wrong. But, in recent years, evangelical anti-abortion activists have taken up the crusade against IVF. “I’m very connected with a lot of pro-lifers who have had their eyes opened to how IVF violates the rights of children, their right to life,” one activist told Christianity Today a month before the Alabama Court’s ruling. “I think a lot of it is they just didn’t know before, but once you know, you don’t unsee it.” In the same article, a researcher for the conservative think tank the Heritage Foundation said she had “observed a shift” among Protestant church leaders who are “beginning to reexamine the moral and theological concerns related to IVF.”

As more Christians have come out against IVF, they also have begun to oppose assisted reproductive techniques that can begin even before sperm meets egg, such as egg and sperm donation and surrogacy. Recently, the anti-abortion movement appears to be mobilizing against surrogacy, the practice wherein someone enlists another person to carry and birth their baby, either by transferring an embryo to the surrogate or using intrauterine insemination with a prospective parent’s sperm and the surrogate’s own eggs. Last month, Pope Francis strongly condemned surrogacy. “I deem deplorable the practice of so-called surrogate motherhood, which represents a grave violation of the dignity of the woman and the child,” the Pope said. “A child is always a gift and never the basis of a commercial contract.”

Candace Owens, the Black conservative Christian commentator, also devoted an episode of her podcast to surrogacy and IVF, which aired on YouTube in 2022 to 2.8 million followers. “The bodies of these surrogates are inclined to reject the pregnancies,” she said. (There is no evidence to support this claim.) Allie Beth Stuckey, a Christian conservative influencer with 436,000 YouTube followers, has been outspoken on this subject. On a recent episode of her show, “No Good Surrogacies: A Surrogacy Baby Speaks Out,” Stuckey interviewed a woman born via surrogacy who resented her parents’ choice. “In surrogacy, you’re purposely creating motherless and fatherless children,” said Stuckey, “and egg selling and sperm selling, it’s the same kind of thing.”

The hostility of many of these activists is motivated by their perception of assisted reproduction as a threat to traditional family structures—largely because the techniques can help LGBTQ people form families. Last month, Owens posted a Facebook video in which she claimed that IVF is “attracting a lot of wealthy lesbians, a lot of gay people, who are using it and creating designer children.” In a December post on X, far-right live streamer Stew Peters called a gay male couple who had a baby through surrogacy “the latest gay couple to steal a baby through the ‘rent-a-womb’ child trafficking racket.” That same month, Matt Walsh, host of the conservative show The Daily Wire, spoke out against LGBTQ couples using IVF. “The child will be deprived of what he needs, which is both a mother and a father, so that the gay couple can get what they want,” he said.

Should the couple struggling to have a baby be heterosexual, however, activists often recommend dubious treatments. Just as the anti-abortion industry has capitalized on misinformation about hormonal birth control promoted by wellness influencers, it has also leveraged the work of fertility influencers who hawk supplements, diets, detoxes, exercise routines, massage, monitors, and mindfulness. Despite a lack of evidence that these treatments help people get pregnant, anti-abortion groups have endorsed them.

Take the American Pregnancy Association, a website that purports to be a neutral source of information about human reproduction but is actually the project of anti-abortion activists. In its section on IVF, the group promotes its fertility guide, which includes links to purchase supplements, lubricants, and fertility monitors—but never mentions assisted reproduction. Modern Fertility Care, an anti-abortion fertility practice that says its practitioners share a “passion for quality women’s health, marriage, and human dignity,” promotes the work of wellness influencer Jolene Brighten, who sells “adrenal support” supplements for people who have had a miscarriage. Natural Womanhood, a group that calls itself a “health literacy program” but also has ties to anti-abortion groups, promotes practitioners of NaProTechnology to its 14,000 Facebook followers.

Anti-abortion activists have been building this momentum in their campaign against assisted reproduction for years, while the reproductive rights movement has done little to counter it. So focused have pro-choice groups been on the work of preserving access to abortion—especially since the US Supreme Court overturned abortion rights with its Dobbs decision in 2022—there appears to be little energy left to fight for the prospective parents’ rights to treat their infertility. Major reproductive rights groups support assisted reproduction, but few of them have programs specifically dedicated to advocacy around access to the technologies. Assisted reproduction remains loosely regulated, not covered by most insurance, and outrageously expensive: The cost of a single cycle of IVF ranges from $15,000 to $30,000.

The Alabama decision will almost certainly end up in the US Supreme Court, where it is likely to meet some sympathetic justices. If they were to outlaw IVF, a host of weighty questions would have to be answered. Who will pay for the indefinite storage of the hundreds of thousands of embryos in freezers at IVF clinics across the country? Could IVF patients be forced to choose between using all of their frozen embryos themselves or “adopting” them out to strangers? If these embryos are all considered to be babies, what other rights do they enjoy? And if a mistake should result in their destruction, what are the consequences? In Alabama, these questions are no longer hypothetical. Meanwhile, you can bet that anti-abortion activists nationwide—who hope that Alabama has set a precedent—are working on the answers.