Mother Jones; Kim Chandler/AP; Getty; Unsplash

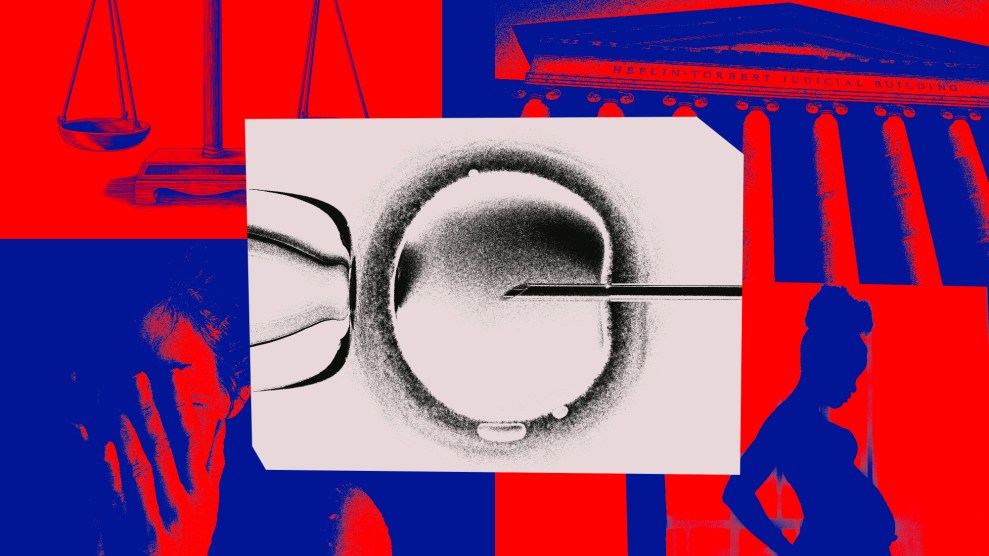

In Alabama, the state Supreme Court ruled this week that frozen embryos can now be considered children under state law. The all-Republican court called on anti-abortion language in the Alabama Constitution, quoted Biblical scripture for backing, and invoked an 1872 state law that grants parents the right to sue over the death of a minor saying it “applies to all unborn children.”

As we have previously reported, the enshrining of fetal personhood can have drastic consequences. And the effect in Alabama has been immediate. Since the decision, multiple in vitro fertilization, or IVF, clinics have suspended their services—leaving patients and providers in legal limbo, searching for answers about what to do with preexisting embryos and already planned retrievals.

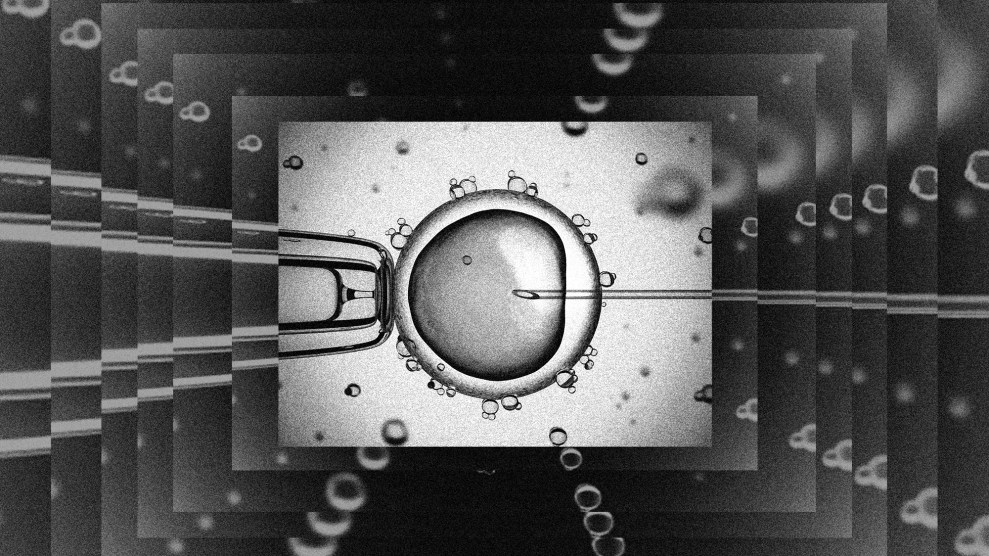

IVF is used as a treatment for those struggling to get pregnant. About 2 percent of births in the United States are because of this technology. It is an expensive process—a single IVF cycle can cost upwards of $30,000—and often a complicated one. By 40, women have a less than 10 percent success rate. IVF is also uniquely a chance for queer couples to have both partners participate in the embryo creation process.

The court decision leaves the future of IVF and other fertility treatments in Alabama uncertain. Following the ruling, Democrat legislators in the state filed a bill that seeks to protect the process.

To discuss the impact, I spoke with Katie, who asked to go by her first name, a former worker at the IVF clinic Alabama Fertility and someone who successfully had a daughter through the process. We talked about her experience with IVF, what this ruling means for patients, and her fear for the future.

What was your initial reaction when you heard the news this week?

It broke my heart. As of [Thursday], Alabama Fertility, which is the clinic that I used to work at, has paused all new IVF treatment cycles. My position was actually the IVF financial counselor. So I spoke to all of our IVF patients that came through the office. I’m the one who told them, “It’s gonna be $20,000 to get this baby that you so desperately want”—breaking the financial news that no one wants to hear. This is a hard road for people.

You mentioned the cost as such a big part of this. Under the ruling, people in Alabama may now have to leave the state to get IVF. How would the cost of having to travel impact the kinds of patients that you were talking to?

It’s definitely going to make an impact. For now, if these patients are having to go out of state to do this, they’re tacking on travel cost, possibly hotels, flights, meals—it’s extra thousands of dollars for these patients who are already spending tens of thousands of dollars to have the baby that they want.

Could you just tell me about your IVF journey?

I was with my now ex-wife and at first we did “known donor“—like a lot of couples [we did that first] to help with the cost. Because, obviously, fertility is a very expensive journey to start. We did that for a little over a year. In January of 2018, we got our first positive pregnancy test. Sadly, that ended in a miscarriage about two weeks later.

After that, we were like: we’ll bite the bullet and do fertility treatments. My OB-GYN performed intrauterine inseminations in his clinic and so we did two IUIs there and had a chemical pregnancy with one. We tried again and had another six or seven-week loss with that. My doctor told me after I had my second loss that it was just like being struck by lightning twice, it doesn’t really happen. Well, then it happened a third time and I’m like, there’s obviously something going on.

We ended up traveling two and a half hours to Alabama Fertility in Birmingham. We did one other IUI there and another loss. Then it was the summer of 2018 and I was just kind of done at that point.

When we started our journey we both thought that we were never gonna do IVF—we just didn’t have the funds. My mom came to us, I was still about 24, and she said her insurance has fertility coverage. So we ended up going through one IVF cycle in October of 2018 at Alabama Fertility and I had 16 eggs retrieved. By the time that we got to day six, I had three embryos remaining. And at that time, after just having so many losses, we decided to do genetic testing on the embryos. After the longest two-week wait of my life, we got our results back and we had two genetically normal embryos that we were able to use. In December of 2018, we transferred one embryo and that actually decided to stick around and so now I have a four-and-a-half-year-old.

This process of IVF gave you your daughter. Had this been decided by the court whenever you were trying to go about this process, God knows what would have happened.

It fucking sucks, honestly. It is mentally, physically, and emotionally exhausting when you have one miscarriage—but multiple miscarriages on top of that. It’s hard to imagine what could have happened if this would have been passed four or five years ago when we did IVF.

You were using IVF in a same-sex relationship as well. How could this ruling uniquely impact people in queer couples like you?

Queer couples already have to make the decision of whose eggs they’re going to use, which can be a hard decision for them to make at all. We knew from the get go: We are doing this one time. This is the only shot we have. We’re going to use mine. But for the couples who both want to carry their own children, they are asking, “Do we spend all of this money to go through this and end up having 40 embryos stored? We’re not going to have 40 kids.” But if this ruling stands and doesn’t get overturned, that’s a reality for a lot of people. Because 20 eggs being retrieved is a normal cycle for some people. I’ve seen as many as 45 eggs be retrieved.

This is all happening within the context of Alabama’s abortion ban. How do you feel about abortion and restrictions in the state?

I am definitely pro-choice. Everyone’s situation is different.

How do you feel about lawmakers and judges across Alabama lumping together IVF restrictions and restrictions on abortion?

They’re completely different. Most of the embryos that are discarded at a fertility clinic would not make a baby, they are embryos that don’t meet the criteria to be frozen. Are there embryos that may be genetically perfectly normal that patients are discarding because they’re done with their family? Yes. I get it, those embryos could possibly turn into a baby. And there are options to donate to people who want to do embryo adoption or to donate to science for research. That is the parent’s choice to make—who helped create those embryos—not the government who’s just sitting behind a desk.

I’m wondering how you would explain this all to your daughter?

I will tell her that it’s her body and her choice to do whatever she wants with that. But there are men in this world that want to take that away from her. She needs to stand up to them and let them know that it’s not their choice of what she does with her body and her embryos and her future babies.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.