President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva at a ceremony marking one year since the attacks on the presidential palace, the National Congress, and the Supreme Court.Ton Molina/NurPhoto/Zuma

This story was originally published by the Guardian and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

What a difference a year makes in the Brazilian Amazon. At the start of 2023, I wrote about the green shoots of the rainy season and feelings of hope inspired by the new president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who promised to strengthen Indigenous rights and aim for zero deforestation. Twelve months on, both the vegetation and political optimism are drying up.

The most severe drought in living memory has finally been broken, but the rains are late and weak compared with previous years. The Xingu River is far lower than normal for January. The pulse of forest growth is also fainter—the new vegetation does not push out as far into the road as it did last January. The neighboring cattle pasture is faring even worse. The forage grasses, known as capim, were so severely burned that they have not grown back, leaving the hillsides brown and the cows emaciated. Several of the poor, skeletal beasts have escaped their fields and wandered towards our community in search of food. Local people say more than a dozen cows have died of starvation at this one ranch, and countless others elsewhere.

Less obvious, but in many ways more worrying, is the dearth of leafcutter ants. These large-mandibled insects are usually everywhere, slicing and carrying vegetation in columns to create fungal gardens in their nests, which spread out over dozens of meters in Gaudi-esque towers and mounds. Entomologists say these ants have the second most complex societies on Earth, after humans, and they are the dominant herbivores in the South American tropics, trimming about a sixth of all the leaves produced in the forest. This stimulates new plant growth and enriches the soil. Not for nothing have these ants been described as ecosystem engineers.

Each day, I pass three big nests of leafcutters on my daily walk with the dogs. Just over a year ago, I ventured too close during the annual revoada, when the winged females set out on their nuptial flights followed by clouds of males. It is a sensitive time for the insects and the soldier ants were in fiercely protective mode. I was driven away with my foot bloodied and me howling with pain.

Despite this, I have never ceased to admire these tiny, powerful creatures so I was dismayed to discover that all four nests are apparently lifeless. The mounds appear deflated, there is no newly excavated soil at the entrances, and not a single leafcutter ant to be seen. This is bizarre as a healthy colony can have 3.5 million members and they never previously stopped working. Entomologists tell me they may have relocated or been wiped out by the prolonged dry season. It is an alarming reminder that the weakening of forest resilience takes many forms and the impact of the drought remains incalculable.

Human-caused global heating and deforestation are parching the forest—and not just over the last year. Scientists have found the Amazonian dry season is getting hotter, drier and longer. Fifty years ago, it lasted four months. Now, it is five. This is causing a die-back of trees and other species that are being pushed beyond their survival thresholds. An ecosystem-wide collapse that would turn the Amazon into a savanna draws ever closer.

Lula knows this. In a speech at Cop28 in Dubai last November he told the world he was shocked that the region’s rivers, which are the greatest freshwater source in the world, are at their lowest level for more than 120 years. He said this was a global climate problem and called on other countries to make a greater effort. “Even if we do not cut down any more trees, the Amazon could reach its point of no return if other countries do not do their part.”

But his own government’s efforts to protect the forest and its people have been mixed. A first-year report card for Lula would show progress compared with the low benchmark set by the previous far-right administration of Jair Bolsonaro, but also failed promises, political weakness and worrying signs of regression.

First, the all-important good news. Deforestation in the Amazon has slowed by about 50 percent over the past year. For the first time since 2018, the clearance rate was less than 10,000 square kilometers in the 12 months until July 31. Still more encouraging, the loss of tree cover in Indigenous territories fell by 73 percent.

The bad news is that, even with this deceleration, on average close to 1 million trees are still being chopped down or burned every day in the Amazon. Countless more died because of the drought and this will worsen the degradation of the forest. Overall, there is no doubt the Amazon finished 2023 in a worse condition than it started, though sadly that has been the case for every year in the past half century.

There are other causes for concern. The Amazon’s southern neighbor, the Cerrado savanna, suffered the largest devastation since 2016 as a result of the expansion of soy plantations and cattle ranching. This repeats the public relations ruse of earlier Lula administrations, which reduced deforestation in the globally center-stage Amazon, while giving a green light to destruction of the important but lesser known Cerrado.

It is a similar story for Indigenous rights. Lula was a true pioneer in creating a separate ministry for this and his government has recognized six new territories, which numerous studies have shown is the most cost-effective way of conserving forest and sequestering carbon.

Yet, he has been outmaneuvered by a hostile congress, which has passed a new law, known as Marco Temporal, to limit Indigenous land approval.

This is not the only challenge to the president’s authority. A year ago, Lula faced down an attempted coup by Bolsonaro supporters, including elements of the police. The army sat on the fence, which was hardly a vote of confidence. Since then, the military has neglected to support the government’s efforts to remove thousands of illegal gold miners from Yanomami territory. As a result, the Lula administration has lost control over those lands and failed to alleviate a humanitarian disaster. Although the government spent $200 million and mobilized 2,000 healthcare workers to the region, 308 Yanomami died from preventable diseases between January and November—little different from the toll during Bolsonaro’s last year in office.

Meanwhile, a new and still greater threat is emerging in the shape of a paved highway through the heart of the western Amazon. The planned BR-319 upgrade from Manaus to Porto Velho would devastate one of the last great, relatively undisturbed areas of the rainforest because roads have always been precursors to illegal logging, mining, land clearance, and invasions of Indigenous lands. The project has been resisted for many years on the basis of expert scientific advice. But last month, lawmakers—with the support of the construction and agribusiness lobbies—passed a bill to dilute environmental licensing requirements for the road, which they have declared a “priority infrastructure necessary for national security.” Lula has effectively given the go-ahead by setting up a BR-319 working group and sidelining the environment ministry in the process.

In a remarkable example of Orwellian newspeak, his transport minister, Renan Filho, says the project will build the “most sustainable and greenest highway on the planet.” He is also seeking project financing from the $1.2 billion Amazon fund, which was set up by Norway, with additional commitments from Britain, Germany and the US, to reduce deforestation and promote sustainability.

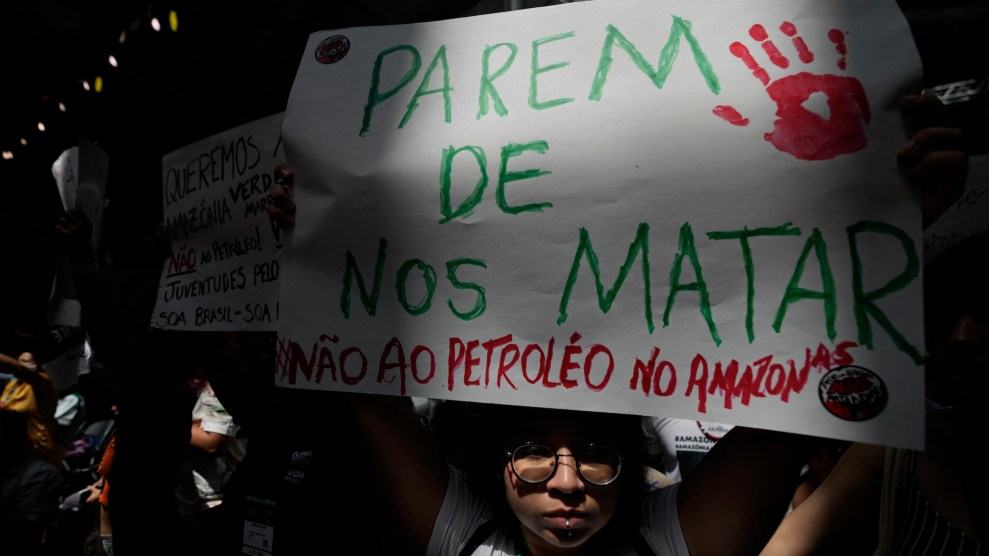

The BR-319 is a flagrant contradiction of those goals. Making such a request makes a mockery of the international fund and the Brazilian government’s environmental credibility. It is a bad joke, not least because one of the goals of the new road is to facilitate oil and gas exploration deep inside the forest, in addition to existing exploration near the mouth of the Amazon. It is the same shortsighted race to cash in on petroleum that is seen in the US, the UK, Canada, Russia, Norway, and other petrol-producing nations.

Lula cannot seem to decide what kind of leader he wants to be. To a global audience, he speaks of the modern need for climate action and promises zero deforestation. But to his domestic electorate, he remains an old-fashioned concrete-and-oil state builder. Compared with last year, there is no doubt he is drifting—or being pushed—ever further away from science and Indigenous rights, and ever closer to business and capitalist extractivism. Given Lula’s weak political position and ideological instincts, it is not hard to understand why. But as a response to record droughts and increasingly deadly weather events, it feels more like a surrender than a compromise.

In the Amazon, the climate crisis is hitting hard. As welcome as the slowdown in deforestation has been, it is not enough and even this is threatened by new roads and oil projects. If the political drift continues, it will not be just the trees, the cows and the ants that start to die off.