Getty

This story is the result of a partnership between The Investigative Reporting Workshop and The Center for Public Integrity.

Osama Mohamed let out a sigh of relief as he and his wife stood at the steps of the US Embassy in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, on the first day of September. Clutched tightly in his hands was the letter he’d been chasing for nearly a year and a half. “Congratulations!” its bolded words declared. “Your US Visa has been approved.”

It had been 16 months since Mohamed, 28, had first applied to the United States Diversity Visa program. His petition became even more urgent in April, when political upheaval in his home country of Sudan prompted by an ongoing conflict that has resulted in thousands of casualties left Mohamed’s family home, near the capital in Khartoum, destroyed.

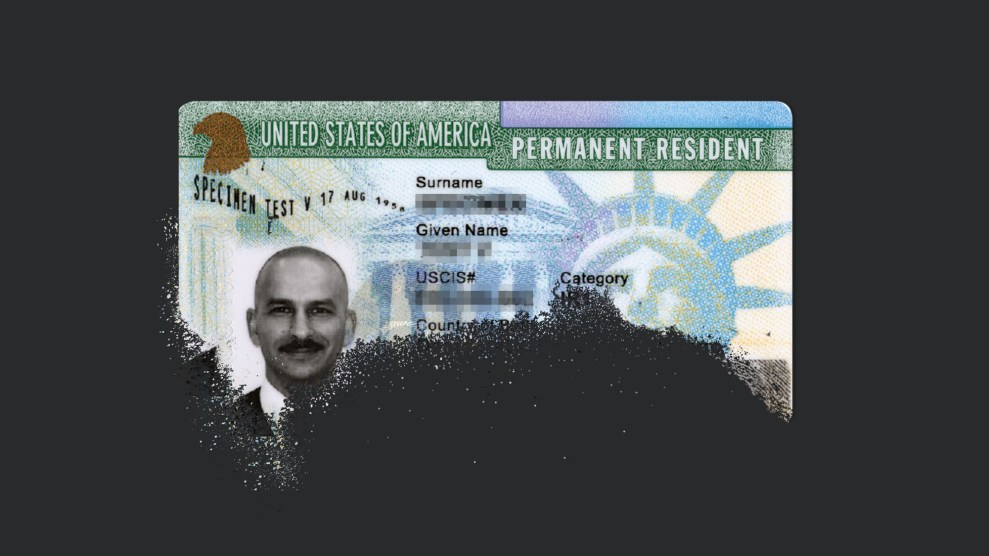

The program has come to be known as the “green card lottery,” in which applicants submit to a laborious 10-step process of petitioning for entry into the United States. Once they arrive, they’re recognized as permanent residents, permitted to work, and enter the path of citizenship. It’s a longshot, by design, intended to open additional visas to would-be immigrants from countries that send relatively small numbers of people to the United States each year.

The final step in the process is an in-person interview, often requiring applicants to traverse international borders to the nearest US Embassy. Mohamed and his wife traveled 700 miles to Addis Ababa for their interview, at which they were told in writing their visa had been approved. It was an “indescribable feeling,” Mohamed recalls, to hold a winning lottery ticket in hand.

Osama Mohamed and his wife, Sara Abdelraheem, spent time at Unity Park in Addis Ababa. At that time, they were waiting for their visa interview.

Courtesy Osama Mohamed

But just a few minutes later, Mohamed heard his name called over the public address system. The worker at window 7 explained that his application needed to be processed further. Mohamed was assured by a case officer that it would all be quickly resolved. Then, a week later, an email arrived: “The Department of State has issued all available diversity visas for the 2023 Diversity Visa (DV) Program,” it informed him. “You are welcome to reapply in future program years.”

Last month, the State Department informed applicants across the world that the US had awarded all 55,000 diversity visas being granted this year, despite the fact that more than 4,000 applicants were still in process, awaiting scheduled interviews for the program—the final step of an arduous process requiring fees, medical exams and often travel to embassies in other countries. Immigration attorneys say they have never experienced so many people being denied slots after reaching the interview stage.

“I’ve talked to hundreds of Diversity Visa families whose interviews were canceled this month, and it’s just heartbreaking,” said Curtis Morrison, an immigration attorney based in San Diego. “There’s no excuse for the incompetence that caused this.”

Immigration experts say that this year’s administrative chaos was likely prompted by a larger wave of applicants who were able to travel internationally to attend interviews than were at the height of the pandemic. They also note that the US has now abandoned the so-called “passport rule” implemented during the Trump administration—that required a valid passport be in hand before someone could apply to enter the diversity visa lottery.

In response to the outrage of attorneys such as Morrison and his clients, the State Department issued a statement in early September noting that the program purposely schedules more interviews than it has slots as a means of ensuring all of the visas are distributed. “Due to the probability that some of the first 55,000 persons selected will not qualify for visas or ultimately choose not to participate in the program, more individuals are selected to participate in the program each year than the number of visas which are available,” the department said.

But immigration attorneys note that, for many families, attending these interviews often requires financial sacrifice and international travel that can take weeks to coordinate. “I am devastated for the families that have made all the preparations for the DV interview only to be canceled at the 11th hour,” said Abadir Barre, a New York-based immigration attorney who said he has heard from families caught in the chaos. “The State Department needs to keep a better track on the number of visas issued so that hopeful applicants are not strung along to the end only to be told their interview is canceled because the cap has been reached.”

Interviews with more than 100 of this year’s diversity visa applicants revealed at least 15 cases like Mohamed’s, in which applicants were told in writing that they would be admitted to the US only to be later informed that the visa they had been promised was gone.

“You wouldn’t imagine that it would become like this and you wouldn’t imagine that you would be an outsider floundering in these statistics,” said Mohamed, who stayed in Ethiopia, hoping he’d eventually receive more clarity from the US embassy but instead amassed $360 in fines for overstaying his scheduled time in the country.

The 30 members of the Senate and House immigration committees, contacted through their congressional offices, did not respond to requests for comment. An aide to one member, who requested anonymity to speak freely, noted that the State Department has undergone efforts in recent years to reduce the risk of fraud within the diversity visa program, which could result in technical problems or individual errors. “With that being said, obviously, in-limbo families should not be provided misinformation,” the aide said.

Asked about these cases in which applicants were told they had been given a visa only to later learn they would not receive one, a State Department spokesperson said that the agency cannot discuss the specifics of individual cases.

“We acknowledge that the conclusion of the 2023 program may be disappointing to selectees who were unable to receive a visa,” the State Department spokesman said via email, noting that those whose interviews were canceled are welcome to begin the process again by applying for next year’s program. “The 2025 Diversity Visa Program entry period will open in early October, and we encourage all who are eligible to apply.”

The Diversity Visa program was launched in 1995, several years after the Immigration Act of 1990 increased immigration quotas and emphasized family reunification in the prioritization of who is allowed into the country. It was designed to allow would-be migrants from countries with historically low immigration rates to the U.S. a better chance at being admitted—and has drawn about 112,000 applicants each year.

“It’s important to recognize the significant role diversity visas have come to play in our legal immigration system, in part because Congress has not enacted needed reforms in more than 30 years,” said Andrew Moriarty, policy analyst at FWD.us, an immigration advocacy group, who noted that it remains remarkably difficult for many would-be immigrants to receive visas to come to the U.S.

Elisbet García, who ran a children’s entertainment company in her native Venezuela, is among those who went to extraordinary lengths to secure a visa through the program in recent years. She first applied in 2018, submitting her entry an hour before the deadline. In 2019 she found out that she, her husband, and their three children had been selected.

By the time García and her family had secured all of the documents they needed and sold their belongings, the Covid-19 pandemic struck, leaving airports, bus routes, roads, and other means of transportation in Venezuela shut down. García insisted to her husband that they find a way. He told her, “’It’s in your hands. Your responsibility if something happens to the kids.”

The family walked 350 miles and crossed the border into Colombia in order to get to a US embassy, where they took the final step of in-person interviews. They passed and were then able to secure spots on one of the few planes departing for the States. By June 2020, they had settled in Atlanta.

Like others who’ve come to the US during the program, García, who was interviewed in Spanish, said that once applicants are promised a visa, they are fully committed to coming to the US and begin making decisions such as quitting jobs and selling homes—actions that cannot be undone.

“The diversity visa is a beautiful promise… at that very moment you receive the news that you’ve been selected, you undoubtedly have trust in the government’s promise,” said Garcia, who lives now in Atlanta and still running her entertainment company. “When you receive the information, you feel this is something meant for you.”

After four years working as the head of sales for a clothing warehouse in Sulaymaniyah, Iraq, Binar Haji Ali, 25, aspired to a higher-paying job in America. “It is so hard to get a job in Iraq because of the political conditions,” Ali said. “So I decided to choose another country to live in, and I think that the US is the best country” for the work that he does.

He applied for the diversity visa program earlier this year, and on Sept. 4 was interviewed by a case worker at the US embassy in Baghdad, where he was told he had been approved for a visa and asked to provide additional medical records. Elated, he resigned from his job and began preparations to move to America. Then, on September 7, he got the same email that was sent to applicants across the world, informing them that there were no more visas available.

“I’m very disappointed right now,” said Ali, who has yet to find a new job in Iraq. “Because I was given a lot of hope.” He said that he’d even begun laying out and packing the clothes he planned to bring to America.

A thousand miles west, Abobaker Mobasher was facing the same disappointment.

For 20 years, Mobasher had dreamed of leaving his home in Sudan to come to the United States. Sometimes he would memorize street names of American cities by exploring Google Earth’s 3D street view. He was overwhelmed with happiness when, in early August, a consul officer at the U.S. embassy in Cairo handed him a letter informing him that his application had been approved. “Congratulations!” the letter declared. “Your immigrant visa has been approved by the consular officer, and it should be processed within two weeks of your interview date.”

But soon after, Mobasher received an alert that his application had been placed back into administrative processing. He assumed that perhaps there was an issue with his and his wife’s passports. When he contacted the embassy, he said, they assured him that the issue was being dealt with. Days of waiting turned into weeks, before ultimately, Mobasher was told that all of the diversity visas available for 2023 had been given to other people.

Mobasher was among a wave of Sudanese applicants who, spurred by an ongoing violent conflict that has left thousands dead and displaced from the Eastern African nation, hoped the diversity visa program would provide his family a pathway to safety.

Carly Goodman, a historian and author of “Dreamland: America’s Immigration Lottery in an Age of Restriction” said that for many would-be immigrants, the diversity visa program is the only chance of making it to the US Other avenues, such as workers’ visas, are more tedious and exclusionary, while the humanitarian visas offered to asylum seekers must be requested in-person at a U.S. port of entry, an option unavailable to those fleeing conflicts in many parts of the world.

“You hear people say ‘Why don’t you just come the right way?’” Goodman said. “There’s this kind of irony, which is really the diversity visa lottery is the only way for…most people around the world have to have a chance to come into the United States.”

Given the administrative errors and the ongoing conflict in Sudan, Mobasher said Secretary of State Antony Blinken should authorize additional visas “to address the Sudanese cases who have become stateless citizens and have struggled to reach the interview” —cases like that of Mohamed Abdelrahim.

After being told his family had been approved for the diversity visa program, Abdelrahim, 39, spent thousands of dollars compiling medical records and on flights to get himself, his pregnant wife, and their two sons from Sudan to Tunisia, where in January they arrived with just a single suitcase between them. But at the US embassy, they were handed only three visas—not four. A consular officer explained to Abdelrahim that his name had been misspelled in the system and so his visa had not been processed. His choice was to remain behind while his family departed for the US or for everyone to remain and reapply for the program next year.

Mohamed Abdelrahim celebrated his son’s kindergarten graduation. Months later, he was denied his visa after a misprint in the system, leaving him separated from his family.

Courtesy Mohamed Abdelrahim

Abdelrahim chose to send his family ahead, remaining in Tunisia where he hoped to sort out the problems with his application before this year’s program closed at the end of September. On September 5, he was told that the administrative errors had been fixed but that there was now another problem—the medical exam that he submitted had expired in July and he’d need a new one. He began scrambling to set up a new exam, but two days later the State Department announced this year’s visas were all gone.

In the months since they departed, Abdelrahim’s family has settled in Dayton, Ohio, and his wife—whose doctors have sent letters to the State Department on their behalf—is due to deliver their third child in mid-October. They’re in the US to stay. But it’s unclear when, or if, Abedelrahim will be able to join them.

“It separated me from my family,” said Abdelrahim, who for the time being moved to Libya. “My wife is going through the most difficult days of her life and needs my support.”