On January 11, 2021, five days after Donald Trump’s supporters stormed the Capitol, CNN published an article titled “Experts Warn That Trump’s ‘Big Lie’ Will Outlast His Presidency.” It quoted Timothy Snyder, a historian who wrote the 2017 bestseller On Tyranny. “The idea that Mr. Biden didn’t win the election is a big lie,” Snyder said. “It’s a big lie because you have to disbelieve all kinds of evidence to believe in it. It’s a big lie because you have to believe in a huge conspiracy in order to believe it. And it’s a big lie because, if you believe it, it demands you take radical action.”

In the two years since, the phrase “Big Lie” has become central to the story of how Trump incited violence at the Capitol. Opening the sixth House Select Committee hearing on the coup attempt, Chairman Bennie Thompson (D-Miss.) said that Trump’s “multipart pressure campaign…to block the transfer of power” was an “effort based on a lie, a lie that the election was stolen, tainted by widespread fraud—Donald Trump’s Big Lie.” Rep. Stephanie Murphy (D-Fla.) echoed the mantra at the next hearing, saying that “millions of Americans were deceived” by Trump’s Big Lie of voter fraud.

And of course Trump did lie about widespread voter fraud for months before any votes were cast and right up through the rally where his supporters gathered and then breached the Capitol, unleashing carnage. But it is insufficient to claim that the Big Lie is merely that the 2020 presidential election was stolen or that Trump’s election-fraud conspiracy was the root cause of the riots. As we confront the insurrection on its two-year anniversary, it’s important to remind ourselves of what motivated the rioters that day: the idea that the United States is for white people, whose power must be protected at all costs.

Pro-Trump supporters storm the U.S. Capitol following a rally with President Donald Trump on January 6, 2021 in Washington, DC.

Samuel Corum/Getty

Robert Pape, a professor of political science at the University of Chicago, has been gathering information on rioters who faced prosecution for their involvement on January 6. He and his “little army of researchers” have analyzed 890 insurrectionists and the 439 counties in 47 states from which they came. The rioters were 92 percent white and 86 percent male. Only 14 percent had extremist ties. They were far less likely to be unemployed or have a criminal record than right-wing protesters arrested earlier in the Trump era. They were also older, mostly in their 40s and 50s. But what especially jumped out to Pape and his colleagues was that more than half were from counties that Joe Biden won. The more rural a county was, and the more its voters favored Trump over Biden, the less likely it was to produce an insurrectionist.

There was another striking common denominator: The more a county’s white population declined, percentage wise, the more likely it was to send a would-be rioter to the Capitol. “Race is the primary factor,” Pape says, accounting for “as much as 75 percent of the energy underneath the insurrectionist movement.” It’s not that the rioters were duped by Trump, but that his lies found fertile ground amid their fears. “The word ‘disinformation’ is off,” Pape says. “It’s about demographic change and whether you’re afraid of it or not.”

That’s true not just of the rioters themselves, but also of people who agree with them. Pape’s team conducted two national surveys, which suggested that 21 million Americans—8 percent of the body politic—believe that Biden stole the election and that violence would be justified to restore Trump to power. They identified two key conspiracies undergirding these dual beliefs: Nearly half the people who hold them are convinced there is a “secret group of Satan-worshipping pedophiles” running the country. And a whopping three-quarters believe in the so-called great replacement, the idea that white Americans are being supplanted by people of color.

In other words, even though race was not the only factor driving the insurrection, the data Pape’s team collected shows that white grievance was the primary motivator. “There’s a clear racial cleavage that you see in our data, and that is what is also captured in the ‘great replacement theory.’”

To believe that whiteness is on the decline is to accept what Theodore W. Allen, author of The Invention of the White Race, calls the Great White Assumption: “the unquestioning, indeed unthinking acceptance of the ‘white’ identity of European-Americans of all classes as a natural attribute rather than a social construct.” This assumption is what allows the media to discuss a point of paranoia-fueled Klan dogma—that whiteness is a thing to be protected and Blackness a thing to be negated—as a “theory.”

Such distinctions—between reality and the stories we tell ourselves— matter a great deal. Because to counter not only Trump’s lies but also the reasons they resonate—the lies within the lies—we must understand what it is we’re facing. Otherwise we miss opportunities to transform the systems that uphold America’s story by means of fiction instead of truth. As Pape puts it, the insurrectionists “are motivated by what they see as their interest to believe the lie…They’re developing this understanding of their interests where race is at the center of it.”

“This isn’t just about disinformation as magical thinking,” he adds. “There’s a conservative set of beliefs here.”

Indeed, narratives of whiteness under threat are conservative talking points as old as the Civil War. When the “radical Republicans” protected Black enfranchisement by passing the 1866 Civil Rights Act and the 14th and 15th amendments, they created a voting bloc large enough to guarantee Republican control of Congress. But then, during the runup to the 1875 elections in Mississippi, two white paramilitary organizations with close ties to the pro-slavery Democratic Party kidnapped and executed local white and Black Republicans and forced rival candidates to remove their names from the ballot. The Democrats justified this coup by falsely accusing Mississippi’s Republican governor, Adelbert Ames, of incompetence. They also blamed “negro militias” and fear of “negro rule” to explain why white Democrats had indiscriminately murdered hundreds of Black people.

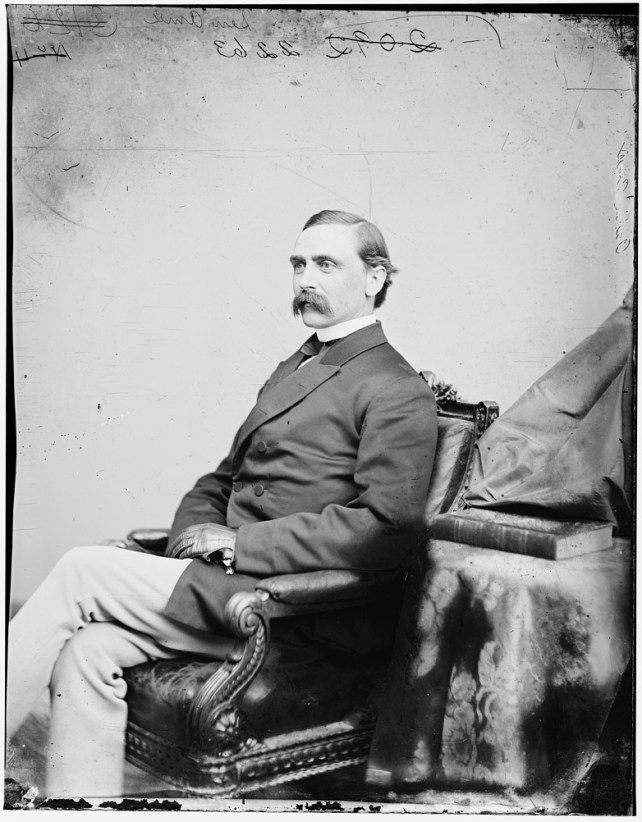

Adelbert Ames, governor of Mississippi.

Library of Congress

The next spring, the US Senate formed a special committee to investigate. It reported that on Election Day “at several voting-places, armed men assembled, sometimes not organized and in other cases organized; that they controlled the elections, intimidated republican voters, and, in fine, deprived them of the opportunity to vote the republican ticket.” As part of the investigation, Angus Cameron, a Republican committee member, questioned Judge Josiah Abigail Patterson Campbell, a Mississippi Supreme Court justice and former Confederate. He asked Campbell why most white men in Mississippi were attached to the Democratic Party. “When the war ended, the people of this country to a very large extent regarded the reconstruction measures of Congress as an hostility to the people of the South,” Campbell said, and that “led the people of the South to believe, whether right fully or wrongfully, that they were the objects of vengeance and the subjects of punishment by the government of the United States.”

The Senate committee report explicitly condemned white grievance and Americans who “look with contempt upon the black race and with hatred upon the white men who are their political allies…who in former times were accustomed to the exclusive enjoyment of political power, and who now consider themselves degraded by the elevation of the negro to the rank of equality in political affairs. They have secured power by fraud and force, and, if left to themselves, they will by fraud and force retain it.”

Despite this admonition, Congress did not employ the new federal safeguards—the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments, plus two Enforcement Acts designed to give the amendments teeth—to punish the Mississippi mobs. The results of that stolen election were allowed to stand. Gov. Ames resigned, and some of the Democrats who usurped power were sworn into the Senate. One was Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar, a former Confederate colonel who went on to help broker the Compromise of 1877, the pact that, following the disputed election, let Republicans keep the presidency in exchange for removing federal troops from the South—thereby putting an end to Reconstruction.

Let’s now toggle back to the present to consider how future Americans will remember Trump’s attempted use of citizens and militia groups to overturn an election. It would do history a disservice if we were to portray the insurrectionists as race-neutral victims of Trump’s swindle rather than what they are: junior partners of white supremacy.

“If you keep missing the big thing that’s going on, you’re never going to be able to deal with it,” Pape says. “There’s a good reason why we’re not making much progress, and it’s because we’ve been captivated by this idea” that the rioters were under the spell of Trump’s lies.

America remains menaced by our collective lack of honest self-reflection. If a significant segment of the populace goes unchallenged in rooting its identity in myths of the immaculacy of whiteness, and is willing to preserve that identity through violent acts, we perpetuate the lie—and the violence. If present-day domestic threats cannot move our society to confront itself, perhaps remembering those from the past might.