The first thing Dr. Curtis Boyd did when he arrived at work one cloudy Monday morning in January was turn on his radio. It was 1973, and Boyd, an ordained Baptist minister, had been providing underground abortions for five years, most recently out of a mountaintop house in Santa Fe, New Mexico. The only people who knew the location of his clinic were members of the Clergy Consultation Service, a national network of faith leaders that discretely connected patients to reliable, and safe, doctors. As far as Boyd knew, he was the network’s only provider in the Southwest.

A group of Texas women had flown in that morning for appointments, but Boyd was distracted. A Supreme Court decision on Roe v. Wade was expected any day now. He kept one ear tuned to the news as he readied himself for the day. When the story broke that the Supreme Court had recognized the right to an abortion, Boyd and his nurse “looked at each other somewhat in shock” and then embraced. “It’s over, it’s over, thank God at last it’s over,” he says. He no longer had to live in fear that he—or worse, one of his patients—might end up in jail.

Boyd’s career as an abortion doctor in many ways encapsulates the nation’s long-fought abortion wars. From 1968 up until the Roe decision, Boyd performed between 25,000 and 35,000 abortions, first in Texas and then in New Mexico, where a state law had loosened restrictions on abortions in certain cases. The Clergy Consultation Service, which grew to include doctors from Detroit to Puerto Rico, and even Tokyo, helped an estimated 450,000 women end their pregnancies before Roe, making it the single-largest underground abortion network known in the United States.

Once abortion became legal, Boyd operated in the open—albeit under constant threat from foes of abortion rights. And even as conservative religious leaders organized congregants into anti-abortion voting blocs, Boyd found ways to integrate religion into his practice.

Now 85, Boyd is still providing abortions. And after the fall of Roe, his old work has taken on new meaning. Today, a similar, if less formal, network of pro-abortion faith leaders is emerging—many of whom are once again referring their patients to Boyd. And although he’s keen to adapt the lessons of the CCS to our current moment, Boyd is disappointed that it’s necessary. “Little did I know that it was not over,” he says. “I never thought we would come back to this.”

Growing up in a rural subsistence farming community in East Texas, Boyd’s childhood centered around “working the farm, going to school and going to church.” When they weren’t doing one of those things, Boyd and his brother would romp through the woods—often walking the two miles to their grandmother’s house. A lay midwife who’d had the first of her seven children when she was just 15, she secretly provided abortions to the women in their community, a fact Boyd would only discover decades later.

Like many families in the area, the Boyds had migrated to Texas from the South after the Civil War and were faithful members of the local foot-washing Baptist church. By the time he was 15, Boyd had memorized much of the New Testament. Church elders said he had been called to preach. Soon after, they ordained young Curtis, and he began giving sermons at neighboring churches. But as he grew older, Boyd began to have doubts about the very literal way his community interpreted the Bible. From books in his Athens, Texas, high school library, Boyd realized there was much about religion he hadn’t been taught—that God hadn’t written the Bible in English, for instance. He was also awakened to the consequences of an unintended pregnancy. He’d developed a crush on a girl in his algebra class, but when he went to ask her out, his friends warned him that she had a baby at home and was therefore a social outcast. “I thought, ‘This is just not right, it’s just not fair, and something needs to be done about this,’” says Boyd. “I never expected to be able to do anything about it.”

As an undergraduate at Texas A&M, Boyd realized that his interest in medicine was an honorable way out of the particular version of a religious life that his family had imagined for him. He went on to medical school at the University of Texas, Southwestern Medical Center, in Dallas, where he ventured into the local Unitarian Universalist Church one day and was struck by its humanitarianism. “That was really my first liberalizing experience,” Boyd says. “I became more open minded to different ways of looking at the world.” Just as one prayer thanked “all the helpers of humankind,” Boyd wanted to help others because it was the right thing to do, not only because religion demanded it.

With his degree, Boyd returned to Athens and opened a small primary care practice. But he still made time for Sunday services at the Unitarian church. And it was there that he met the Rev. Bill Nichols, who was involved in the larger Unitarian efforts to discuss the stance the church would take on social issues like abortion. In the late ’60s, the Unitarian general assembly passed a resolution urging “that efforts be made to abolish existing abortion laws except to prohibit performance of an abortion by a person who is not a duly licensed physician, leaving the decision as to an abortion to the doctor and his patient.” Boyd and Nichols became close friends, and Nichols would regularly ask Boyd about his opinion on abortion as a medical professional. When Nichols was contacted by two ministers at Southern Methodist University who were members of a new abortion rights organization, he asked Boyd if he might be willing to speak with them.

The group had been conceived during a fall 1966 luncheon between three Christian ministers and Lawrence Lader, a journalist who was working on a book calling for abortion to be legal and accessible. The ministers, two Episcopal priests and a Baptist, wanted to know how they might plug into the burgeoning movement, and Lader suggested organizing clergy in New York. The next spring, a statement from 21 reverends and rabbis published in full in the New York Times announced the creation of Clergy Consultation Service on the grounds that they were bound to “higher laws and moral obligations transcending legal codes” and that it was their “pastoral responsibility and religious duty to give aid and assistance to all women with problem pregnancies.”

A faith-based abortion network may sound strange today, but it wasn’t until the late 1970s that Christian denominations other than Catholics adopted an anti-abortion stance. In a 1968 edition of Christianity Today, the Christian Medical Society wrote, “Whether the performance of an induced abortion is sinful we are not agreed, but about the necessity of it and permissibility for it under certain circumstances we are in accord.” Even as the Rev. Jerry Falwell and his ilk preached abortion’s evils and Operation Rescue organized its Summer of Mercy protests, Boyd didn’t see any conflict between his faith and abortion. “Women had a problem and needed help,” he says. “Abortion was not the problem. The unwanted pregnancy was the problem.”

At first, the SMU chaplains asked Boyd if he would be willing to find reputable doctors in the Southeast to send women to for abortion care. Boyd agreed, and he scoured the region, even visiting a few clinics in Mexico. But he didn’t feel good about sending women to any of the places he’d found—many weren’t operated by actual doctors or seemed too focused on the profit they could earn by treating desperate patients. “They kept waiting on me and I kept waiting on a miracle,” he says. Eventually, they made a different ask: Would Boyd consider performing the abortions himself? “That stopped me from talking,” Boyd says. “I’m risking my medical license, I’m risking going to prison.” He knew in his heart what he was going to say, but he also knew that he had to be absolutely sure of his decision.

His services were not publicized, and Boyd kept a low profile, telling only a few select people what he was doing. But people talk in small towns, and the local police noticed a lot of out-of-state license plates heading to Boyd’s clinic. They began following—and stopping—visitors. A few college-age patients were caught with marijuana, leading officers to wonder whether Boyd was dealing drugs.

That’s when Boyd realized he had to go somewhere bigger. He relocated to Dallas, not far from the First Unitarian Church—the same church where congregants would soon connect a young, unhappily pregnant woman named Norma McCorvey, better known as Jane Roe, with the attorneys who would take her case to the Supreme Court. But even in Dallas, Boyd worried that his clinic was drawing too much attention, so he relocated again, this time to Santa Fe, where a mental health exception in the state’s abortion law made his work less risky.

By this time, the Supreme Court had heard oral arguments in Roe v. Wade, but the court tilted conservative and Boyd was worried. He needn’t have been. Within 24 hours of abortion being legalized, the CCS was calling to see if Boyd would move back to Texas, which desperately needed his services. And that’s how he found himself in Dallas once again, this time running the state’s first legal abortion clinic.

Through his networks, Boyd and his wife, Glenna Halvorson-Boyd, who also worked at the clinic, befriended Dr. George Tiller, whose practice in Wichita, Kansas, was one of the only in the country that offered abortions beyond about 24 weeks. Tiller, like Boyd, was a religious man, and employed a minister for his patients who wanted spiritual counseling. This service sent a powerful message “that religion and God is within the walls of the clinic” not the out in the parking lot with the “people damning [patients] to hell and saying ugly things,” Halvorson-Boyd tells me.

The couple decided to do the same in Dallas. They hired a team of counselors, some religious and others not, whom patients could consult separately from the medical conversations Boyd had with them. Halvorson-Boyd was herself a counselor, and listening to patients day in and out, she soon came to realize, she says, that “no one knows what they would do until it’s their pregnancy at that point in their life.” Whatever their decision, Halvorson-Boyd says, “women are moral beings” who “should be the moral agent in their own life.”

It was dangerous work. Like Tiller, the Boyds received death threats. Their Dallas clinic was set ablaze in 1988, causing well over $100,000 in damage. Five years later, Tiller was shot in both arms by an anti-abortion extremist, and another clinic the Boyds had opened, in Albuquerque, was firebombed. But in 2009, the unthinkable happened: Tiller was shot to death outside his church by a “pro-life” zealot. Medical conferences that invited Boyd to speak stopped listing his name on the program, and the FBI added the couple to a list of potential assassination targets.

Pro-life protesters hold crucifixes outside of Southwestern Women’s Options.

Ramsay de Give

Tiller’s murder devastated the Boyds both personally and professionally. They no longer had a place to refer women in their third trimester. But Boyd managed to hire two Tiller-trained doctors for the Albuquerque clinic and learn their specialized techniques. “I would say that probably both of us, in some compartment of our souls, knew that we would take that” work on, says Halvorson-Boyd. Most women who choose to terminate at this stage do so after learning that their fetus isn’t viable or that the pregnancy presents dire risks to their own health. These are usually desired pregnancies, Halvorson-Boyd emphasized, and patients’ counseling needs are intense. “It will always be a very, very small practice with few women. And those women will always be in desperate need of care.”

If the patient is religious, it’s also the time when religion most often enters the procedure room. Many patients, Boyd says, have asked him or the clergy volunteering in the clinic to bless their fetus, in hopes that they might “return the spirit of that pregnancy to its source.”

Boyd used to think there was a chance he might retire, but now, he says, “I don’t even pretend anymore.” He’s clear-eyed about his mortality. He works reduced hours. He is making succession plans to keep his clinics open under a family foundation. But he also knows the need is too great to stop entirely. In retrospect, the two arson attacks in 1988 and 2007 were minor setbacks. For Boyd, the biggest obstacles came in the past few years, just as Roe was about to turn 50.

The first was in May 2021, when Texas passed a law banning all abortions after six weeks. Patient numbers dwindled at the Dallas clinic. One of the clergy who volunteered there, the Rev. Dr. Daniel Kanter, suggested the team start bringing women to the clinic in Albuquerque. In collaboration with the New Mexico Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice, a descendant of the Clergy Consultation Service, Kanter and other Dallas clergy were soon flying in about 20 people to Albuquerque every two weeks.

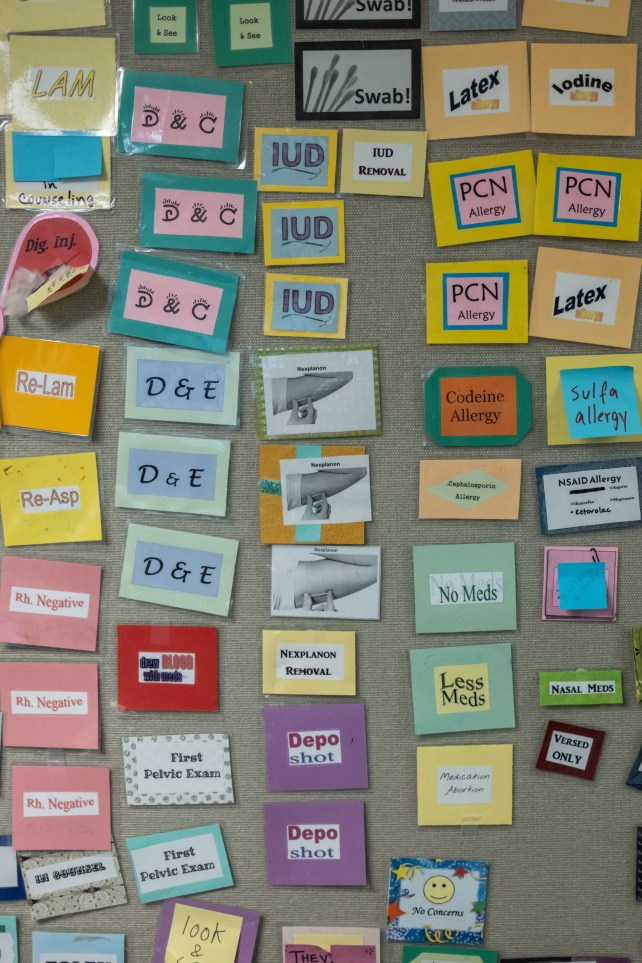

Various patient decals used at Boyd’s clinic

Ramsay de Give

While the Roe ruling had surprised Boyd, the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe came as no surprise. Still, everything changed. Texas law reverted to a 1925 statute that would punish anybody who “furnishes the means for procuring an abortion,” forcing Kanter and his peers to pause their work and reassess their risk. The legal threat, says Kanter, feels higher now than it ever did before Roe. “The state is looking to make an example of someone.” Despite assurances from the Dallas district attorney that no charges would be brought under the 1925 law, some lawmakers have said they want to pass legislation allowing DAs from other counties to prosecute beyond their jurisdiction.

Yet as of November, the clinic has restarted the travel program and are now accompanying as many as 10 patients a week to New Mexico. “So the fight continues,” says Kanter, and “clergy all across the country are organizing.” In Minnesota, faith leaders are strategizing to see how their state could be to the Dakotas what New Mexico is for Texas. Meanwhile, progressive clergy at Faith Choice Ohio are coordinating with Catholics for Choice to expand abortion access there. Nationally, local branches of the Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice are providing financial and logistical support to people seeking abortions.

And there have been other bright spots, including the midterms, which Boyd found “extremely encouraging.” Abortion “won in every state where it was on the ballot,” Boyd points out, and that’s likely “not because people are so supportive of abortion, but because they do support freedom, including the freedom for people to make their own choices, which is encouraging for the future.”

“We have a monumental task ahead of us, but we’re going after it,” Boyd tells me. And on days when things feel too risky or difficult, the couple will just have to look at one another and remind themselves, “This is the life we have chosen.”