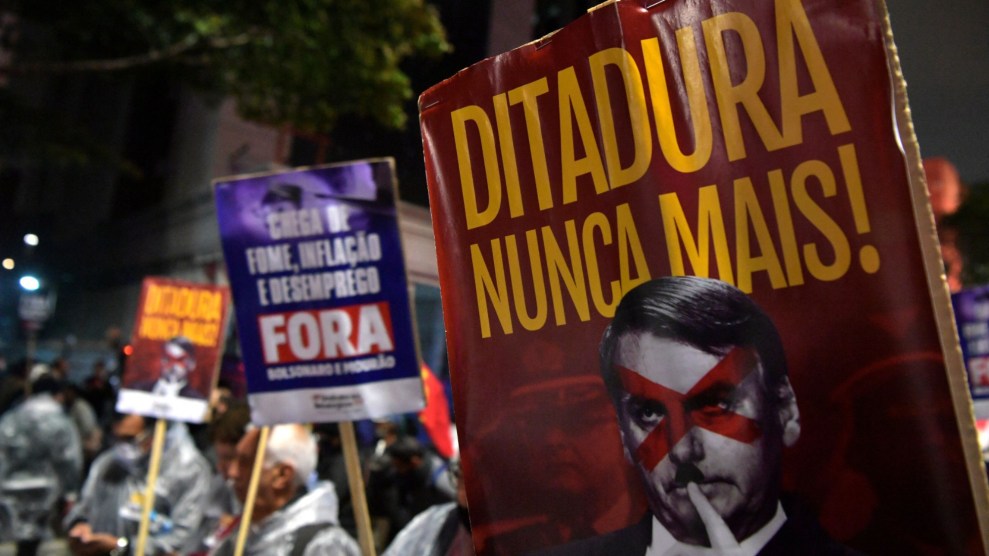

A supporter of President Jair Bolsonaro confronts a supporter of former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. Eraldo Peres/AP

The first time many Brazilians heard of Nikolas Ferreira was the day the newly elected federal lawmaker received the highest number of votes in the country’s 2022 legislative elections—and in the history of the key battleground state of Minas Gerais in southeast Brazil. Born in an impoverished favela, the 26-year-old self-described conservative Christian “defender of the family” and advocate for abstinence until marriage is a staunch supporter of far-right President Jair Bolsonaro, who is running for reelection this Sunday in the final round of the most contentious presidential race in recent memory. Ferreira, a baby-faced member of Bolsonaro’s Liberal Party, racked up about 1.5 million votes, almost 500,000 more than the next best performing candidate for the Lower House, and a monumental leap from the 30,000 that had secured him a city council seat in Belo Horizonte in 2020, when he vowed to be a “wall against the leftists.”

“The culture war is here; get ready,” Ferreira wrote a few days after the early October closer-than-expected first round of the election that saw left-leaning former two-term President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, better known as Lula, come out on top with 48 percent of the votes. He was promoting his online course, which carries the same title as his book, The Christian and Politics: Discover How to Win the Culture War. His mission is to prepare Christians to prevail on the battlegrounds of abortion, gender ideology, and crime—all extremely familiar subjects for American voters and another example of how, in this presidential election in South America’s largest democracy, life is imitating Donald Trump. “Brazil and the United States are mirrors of each other,” former US ambassador to Brazil Thomas Shannon told BBC News.

Bolsonaro, a former army captain and longtime congressman from Rio de Janeiro with a mediocre legislative track record has often been referred to as the “Trump of the tropics.” He rose to power by deliberately evoking “fears, panics, and revulsions” of a perceived deterioration of traditional family values and, similar to Trump, positioning himself as a populist hero and the only true guardian of the people’s will. Ferreira may stand out as one of the most successful exponents of “Bolsonarism”—the MAGA-like reactionary populism cultivated around Bolsonaro and his “God, family, and homeland” motto—but he is joined by many others. Several of the movement’s disciples have been elected to Congress this election cycle, spurring concerns of an ideological hijacking of the legislature by a breed of hardliners. Their performative grievance politics as candidates center on mobilizing dread of social change to manipulate a disaffected electorate and advance an ultra-conservative agenda.

What has taken place during the Brazilian elections this year could easily be mistaken for the GOP’s culture wars, dubbed in Portuguese. In Foreign Affairs, Brian Winter, editor-in-chief of Americas Quarterly, writes, “The campaign’s tone and content sometimes seem to have been cut and pasted from the conservative agenda in the United States.” At an October presidential debate, the incumbent president, who repeatedly cast doubt on the integrity of the electoral process and the institutions overseeing it, doubled down on his signature retrograde discourse. “We want a free country, we don’t want gender ideology, we don’t want drug liberation, and the other side wants it,” Bolsonaro said. “No to abortion, nor the MST [Brazil’s Landless Workers Movement] invading the land, and for the right of self-defense.”

His authoritarian strategy involves creating a political culture organized around an artificial sense of generalized moral panic over a “Holy War” between the pure and virtuous and the heretical and satanic. Opponents of Bolsonaro are presented “as the incarnation of the Antichrist” while he and his followers are the protectors “of the family, the homeland, and the good,” explains political scientist and historian Christian Lynch, co-author of the new book Reactionary Populism: Rise and Legacy of Bolsonarism. “It’s importing the Trumpist techniques to Brazil and adapting them to the Brazilian context.”

Brazil is not alone. The extreme populist model is shared by an increasingly globalized right-wing nationalist movement in Italy, Hungary, and, less successfully, France. It has been championed in the United States by Trump’s former White House chief strategist Steve Bannon. In 2019, Bannon named Bolsonaro’s third son and congressman Eduardo—once described as having “a unique gift for channeling America’s conservative movement with a Brazilian twist”—the representative in South America of his botched attempt at building a transnational far-right populist alliance.

Bannon has called Lula a “criminal puppet of the Chinese Communist Party” and described the 2022 race in Brazil as the continent’s “most important of all time.” In contrast, he has hailed Bolsonaro as a hero, saying “if you look at Brazil, it is very much like the MAGA movement.” In many ways, he told Bloomberg in 2021, “Brazil’s movement is actually more advanced than we are in the United States.” Trump, Bannon volunteered to BBC News in September, could learn a thing or two from Bolsonaro about how to run a campaign.

He also predicted that the outcome of the Brazilian elections could “set the stage” for a Republican takeover of the House in the midterms. “The Bolsonaro election down in Brazil [is] absolutely central and a very stark warning to MAGA and to all the Republicans of the games that are being played in all these elections,” Bannon said on the War Room podcast the day after the first round, raising unfounded suspicions of electoral fraud that have been shared online among US election denialist groups and promoted by Republicans (such as Mark Finchem, a candidate for Arizona secretary of state). “We are not going to allow this election to be stolen,” he said, “because we are going to give a death blow at the ballot box to the Democratic Party as a national political institution, from school boards all the way up to the House and the Senate and the governors’ races.”

As with other Bolsonaro sycophants, Ferreira has built his rough and tumble political brand by lecturing at churches and stoking controversies and outrage over hot-button social issues—and he’s been successful beyond imagining with roughly 5 million followers on Instagram and 2.7 million on TikTok. Among his greatest hits are a viral video in which he protests being turned away from a visit to the Christ the Redeemer statue in Rio de Janeiro for not presenting proof of vaccination against the coronavirus, and another video in which he questioned the presence of a transgender student inside a bathroom at this 16-year-old sister’s school. “If I’m a dad, what do I do?” he asked on a YouTube video that garnered more than 200,000 views. As a city councilor, Ferreira introduced legislation to prohibit the inclusion of gender-neutral language in school curriculum. “I encourage you to pull your child out of that school and put them in a school where the minimum is respected—where there’s one [bathroom] for men and one for women.”

A master of the digital guerrilla warfare that has come to define Bolsonaro’s administration and his troll-like disinformation machine that has become known as the “hatred cabinet,” the newcomer lists as one of his thought leaders the self-proclaimed philosopher Olavo de Carvalho, Bolsonaro’s political guru and a far-right ideologue who lived in Petersburg, Virginia until his death, likely from Covid-19, earlier this year. He espoused the idea that the media, universities, and entertainment industry are corrupted by Cultural Marxism. Another of Ferreira’s role model is Russel Kirk, the “father of American conservatism’ and author of the 1953 classic, The Conservative Mind.

But perhaps the most extreme example of an ideological crusader in Bolsonaro’s Brazil is former Minister of Women, Family, and Human Rights Damares Alves, an evangelical pastor who once preached about a character from Disney’s Frozen turning children into lesbians. In 2020, she reportedly tried to prevent a pregnant 10-year-old victim of rape from getting an abortion. Alves has since been fined for falsely claiming Lula’s government-employed guidelines teaching students how to use drugs. Even more extreme is her creation of a bogus scheme she attributes to no one in particular, to sexually exploit children as young as 3 or 4 by pulling out their teeth so they could perform oral sex. “We found out that these children eat soft food so the intestines are free for anal sex,” she said in mid-October at a church, fictitiously explaining that a move by Bolsonaro to crush that violence had made hell rise against him. “The war against Bolsonaro that the press, the Supreme Court, and Congress raised,” she said, “believe me, is not a political war. It’s a spiritual war.” Nonetheless, she will serve in the Senate after receiving more than 700,000 votes. In the aftermath of the first round, dressed in a t-shirt with “100% Bolsonaro” printed on it, Alves vowed to “fight for the children” and condemned gender ideology as forcing children to choose between different identities.

Ferreira has also claimed to be concerned for the vulnerable children of Brazil. At the 2021 Brazilian offshoot of the Conservative Political Action Coalition conference, he told parents not to “outsource” the responsibility of educating their children to the government, taking a page out of the playbook of the US right-wing parental rights movement. His attacks on Lula suggested the then Worker’s Party candidate would shut down churches, let violent crime go rampant, and allow the “murders of innocents” in the womb. (Cracking down on disinformation, Brazil’s Superior Electoral Court has ordered the video be removed from online platforms and that Ferreira post a retraction on his social media, which he subsequently tried to bury by tweeting dozens of edited photos of the chief justice as Mickey Mouse.) “Your freedom is at stake,” Ferreira warned in a viral post ominously cautioning that Brazil might become a leftist dictatorship.

Conservative hysteria and fearmongering about communism isn’t a new addition to the script of hyper-polarized Brazilian politics. Ahead of the 2018 elections won by Bolsonaro, then Lula’s political heir and presidential candidate Fernando Haddad had to debunk conspiracy theories accusing him of defending incest and distributing erotic baby bottles with penis-shaped nipples, part of what Bolsonaro branded “gay kit,” in schools during his stint as Minister of Education. A post-election poll found that more than 80 percent of Bolsonaro’s supporters believed the lie, which distorted a national anti-homophobia awareness program into being a vehicle for the early sexualization of children. Bolsonaro has latched onto the program despite the fact that in 2011, former President Dilma Rousseff vetoed the distribution of materials after pushback from evangelical members of Congress. More recently, he juxtaposed his own education program focused on “strengthening family ties” with what he characterized as the kit’s obscenity.

“We are living in a world where culture wars have made candidates,” Pablo Ortellado, who studies the rise of conservatism in the political debate and created a Portuguese-language podcast titled Culture Wars: A Battle for the Soul of Brazil, said recently on another podcast. “Bolsonaro is plainly a candidate of moral conservatism.” The culture wars, he added, have become ingrained in society and are dividing the Brazilian population. In a symbolic expression of that division in 2018, Haddad voters brought books to the polls, while some supporters of Bolsonaro, who had eased gun control laws, cast their vote while holding onto firearms.

But the moral underpinnings of the campaigns in 2022 noticeably escalate such tactics, likely because of the growing political influence of the evangelical voter base, which now represents about one-third of Brazil’s population of 215 million. Indeed, the runoff between Lula and Bolsonaro took the shape of a religious battle, with accusations of cannibalism, Satanism, and freemasonry. A few days ahead of the runoff, Pope Francis prayed for the Brazilian people to be freed from hate and violence.

“Lula does not have a pact nor has he ever conversed with the devil,” one flyer said after videos circulated on social media of a man who self-identifies as Satanist declaring support for the candidate. “There are some things that I don’t believe a human being can believe in, but they say it and some people believe it,” Lula said at a public event with evangelicals in an effort to confront lies that if reelected, he would create unisex bathrooms in schools. Official Bolsonaro TV ads have accused his opponent of changing legislation to incentivize abortion—which is illegal in Brazil with exceptions for rape or incest and to protect the woman’s life—and tried to tie Lula, who was imprisoned on corruption convictions later annulled, to crime by claiming he performed well among incarcerated people, although those sentenced and convicted aren’t allowed to vote. Even a cap Lula wore during a visit to a Rio favela has become fodder for false allegations of a link to criminal organizations.

“Without culture wars, there is no ‘Bolsonarism,’” João Cezar de Castro Rocha, professor of comparative literature at Rio de Janeiro State University and author of Cultural War and Rhetoric of Hate: Chronicle of a Post-Politics Brazil said last year, “but with a culture war there can’t be a Bolsonaro government…You can’t govern a country by creating enemies all the time.”

But for the president’s backers, since he is setting the agenda, he’s already won. “Brazil has already changed,” Ferreira said recently in a video explaining that he voted for Bolsonaro because the far-right president dared to say what no one else did. “Today you start a conversation with your family, in an Uber or at the supermarket and people are no longer talking about secondary issues.” Instead, they are talking about what really matters—the loss of freedom. “Retreating can’t be an option,” he emphasized in several posts.

Politics, Ferreira realizes, is all about influence. “There is no such thing as empty space in politics,” he said in an August interview. “If you don’t take it up, someone else will.”