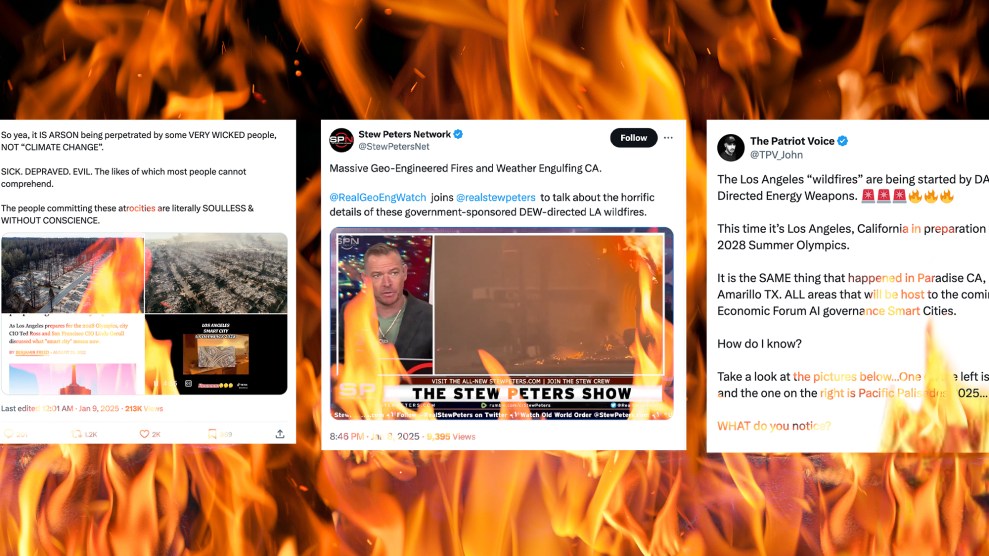

One day leading up to winter break, administrators of the predominantly white New Trier Township High School in the wealthy northern Chicago suburbs announced that “Understanding Today’s Struggle for Racial Civil Rights” would be the theme for a school-wide topical event known as Seminar Day. One of its main goals was to help “students better understand how the struggle for racial civil rights stretches across our nation’s history.” Featuring National Book Award winners Colson Whitehead, author of the acclaimed The Underground Railroad, and Andrew Aydin, co-author of the March graphic novel trilogy about civil rights icon John Lewis, there also would be more than 100 elective workshops and group discussions, some led by students, on such topics as racial microaggressions, cultural appropriation, and implicit bias. A few months before the program, parents were encouraged to attend a session devoted to talking about identity and race.

The backlash was swift and intense. A group calling themselves Parents of New Trier started a Facebook page and a website to denounce what they considered to be the “biased, unbalanced, divisive, and costly” program. They urged organizers to add more conservatives—including former Milwaukee Sheriff David Clarke, who once had compared the Black Lives Matter movement to the Ku Klux Klan—cancel the event, or make it an opt-in day for students. The group even published an annotated version of the speakers’ line-up highlighting such terms as “systemic racism,” “community resistance,” and “Latinos” and described them as “divisive, loaded, biased and in some cases bigoted” language. “If your children attend Seminar Day,” the website suggested, “you may want to encourage them to consider the workshops on comedy, poetry, gospel music, or the Civil War.”

Hundreds of members of the community showed up for a packed school board meeting. The “parochial debate,” as the Chicago Tribune referred to it, made national headlines and op-eds appeared accusing the school of promoting what critics dubbed “racial indoctrination” and “force-fed dogma.” Nonetheless, thousands of people signed a petition in favor of the program. “I’ve never seen this kind of outpouring of support on an issue in my life as an educator,” then-Superintendent Linda Yonke said.

The controversy at New Trier and the divisions it triggered in the community may seem familiar now. But the conflict didn’t take place in the volatile pandemic years when efforts to boost equity and diversity, teach comprehensive history, and implement pandemic-related health measures in schools sparked outrage from concerned parents and culture wars enthusiasts. It happened in early 2017, about a month after former President Donald Trump took office.

Seminar Day ultimately took place as planned, but it forced an elite community to confront racial tensions and issues around representation that, more than five years later, former students, parents, and school administrators are still processing. In retrospect, what transpired in this affluent Chicago suburb was a canary in the coal mine—a trial run for the conservative attack on public education that has since captured much of the nation.

What first drew Paul Traynor, an Indiana-raised video producer and corporate speaker, from downtown Chicago to the North Shore were its well-regarded public schools. Traynor, who has lived in Wilmette for 20 years, sent four of his five children to New Trier High School, which has consistently ranked among the top high schools in Illinois. At times described as a “crown jewel” of public education, New Trier has produced notable alumni, including former Harvard Law School Dean Martha Minow and actors Charlton Heston, Ann-Margret, and Rock Hudson.

“The US public high school at its best,” announced a 1950 Time magazine cover story, with “youthful informality, elderly main building, and alert student body.” The typical New Trier student, according to the pages-long spread, was white and affluent, a profile that has largely remained unchanged in the decades since. The school became the setting for the films Home Alone and Ferris Bueller’s Day Off and, some say, the inspiration behind Tina Fey’s Mean Girls. Today, 78 percent of the roughly 4,000 New Trier students are white and less than 1 percent are Black. New Trier Township encompasses Wilmette, Winnetka, and other North Shore suburban communities, where the median household income is $177,672.

“My sense of NTHS was always that we have the best teachers, they’re very well paid, and much beloved and supported by the community,” Traynor wrote me in an email. Two of his children have already graduated, and two are currently enrolled. “The parents around here are Type-A, and very involved, and demand the best on all fronts.” Even so, Traynor, who’s white, told me over the phone, “New Trier has always had a problem with diversity, for sure.”

New Trier High School.

Courtesy of Paul Traynor

With the motto “[T]o commit minds to inquiry, hearts to compassion, and lives to the service of humanity,” the high school has tried to engage in difficult conversations. As far back as the 1990s and early 2000s, Niki Dizon, the school district’s director of communications, explained in an email, intermittent Seminar Days have focused on the Columbus Quincentenary and the 1492 “discovery” of America, as well as a “learning from tragedy” discussion post-9/11.

But the institution’s lack of diversity clearly has created educational and social limitations. Old yearbooks show photos of New Trier students in blackface and in 1999, a graduate of the class of ’96, Benjamin Smith, went on a shooting spree targeting Black, Asian, and Jewish people. Audrey Moy, a Wilmette resident, and mother of two New Trier graduates, recalls that in 2015 the school suspended two students after one of them posted a photo on social media of Black students from a different school accompanied by a racial slur and the other, offended by it, reposted with a rebuke. At the time, New Trier administrators referred to what happened as an “isolated incident” but sent a letter to parents suggesting that they should use it as a teachable moment. “This is an opportunity for you as a family to discuss topics such as race, use of social media, and harassment at the same time that we are also discussing those issues at school,” then-Superintendent Yonke wrote.

New Trier’s diversity problem plagued the school even after students graduated. “They were getting feedback that students were going out into the world and finding they could handle coursework but weren’t that great at handling people of color because they weren’t reflected in their classrooms or the school—except for the janitorial, lunchroom, and security staff,” said Moy, who identifies as Caribbean, Jamaican, Cuban, and Panamanian and whose husband is American-born Chinese. They grew up in neighboring Evanston, an area more diverse and less affluent than New Trier Township. “I think many people [in this community] feel like they don’t have to learn about other people in the world because they’re in a bubble.”

In 2016, the school organized a Seminar Day to commemorate Martin Luther King Jr. Day and promote discussions about racial identities and systemic racism. That year’s event included talks by Pulitzer Prize-winning author Isabel Wilkerson and Lori Lightfoot, now mayor of Chicago and then president of the Chicago Police Board. It also caught the attention of right-wing Breitbart, led by Steve Bannon at the time, which published posts likening the event to “forced race education.”

Gracee Wallach, who graduated from New Trier that year and was part of a Student Voices in Equity group, remembers being disappointed at the low student turnout. “Probably a lot of the students, if not all of the students, who were not at school would have benefited from being part of these conversations,” Wallach said because they filled a gap in issues being addressed at the school. “The fact that we could have one day, albeit insufficient, was so important for broadening our perspectives as students.”

Looking back at that Seminar Day, Amanda Wong, an Asian American graduate, says some students chose to hang out in the library instead of attending the event. “It was disappointing but not surprising,” Wong says, adding that conversations about race at the school throughout the year felt “isolated and fractured” and that microaggressions were frequent in student interactions.

But these early tensions dwarfed in comparison to what took place in 2017. New Trier High School Superintendent Paul Sally, then associate superintendent for curriculum and instruction, noted that the February board meeting took place a few days before the scheduled event and drew an unprecedentedly large audience. So large, in fact, that the meeting had to be moved to a bigger auditorium. For Sally, it was the moment when it became clear to school administrators the climate had radically changed around discussions about racial justice. “We all sort of said, okay, we need to try and explain what we’re doing as thoroughly as we can,” he explained when we spoke on the phone, “the purpose of it and how it’s student-centered.”

At the meeting, Sally and Assistant Superintendent for Student Services Tim Hayes gave a comprehensive presentation on the structure of Seminar Day and invited students who had been involved in the organizing to talk about its importance. “This Township is not representative of the larger United States and we have a moral obligation to prepare ourselves for our futures beyond this community,” one student said. Greg Robitaille, the president of the school district’s board of education at the time, acknowledged the 600 emails and many phone calls he had received about the topic. “Your passion for this issue is unmistakable,” he said to the audience. “We hear you, on all sides.”

New Trier High School Former Superintendent Linda Yonke and Assistant Superintendent for Student Services Tim Hayes at the school’s Northfield campus.

Sophia Tareen/AP

During the public comment session, a handful of critics of Seminar Day spoke up. “My issues are more like why are we doing politics? And why are we doing this type of politics? Can we have more balance?” a local conservative radio host whose sons had attended New Trier said. Betsy Hart, one of the founders of the Parents of New Trier group that used Facebook to encourage residents to attend the board meeting and protest the content of Seminar Day, complained that supporters of the event were trying to shut down other world views and characterizing her and others as civil-rights history deniers.

Most people in the auditorium and in the community appeared to be in favor of the school’s programming. When one of the creators of a pro-Seminar Day petition signed by more than 5,000 people asked supporters to stand up, the vast majority of the room rose from their seats. Former students shared how not being exposed to a diverse classroom and faculty had impaired them as they entered the larger world. As a result of going to a homogeneous school in a homogeneous community, one alum said, “I felt embarrassingly uninformed about basic facts about race and racism in America.” Another said he couldn’t remember having had a single Black classmate and how offensive jokes would often go unchallenged.

“Life at New Trier can fool us into thinking our society is ‘post-racial,’ simply because we don’t have much racial diversity in our township,” four alumni, including Wallach, wrote in an open letter at the time. “We don’t recognize or question the disproportionate amount of white faces in the hallways; we don’t regularly examine issues of inequity through the lens of race—and this is all because we don’t have to. By not talking about race and not recognizing that we aren’t talking about it, we are attempting to sweep it under the rug, which only perpetuates a cycle of covert bigotry in this community and beyond.”

The day after the crowded school board meeting, Robitaille, the board president, issued a statement reassuring parents there was no evidence that the organization of the event “was driven by any political or social ideology or agenda.” However, the message added, they weren’t going to “question the very existence of racism” for the sake of some “extreme notion” of balance.

“We really believed in what we did and knew it reflected the values of the community and of New Trier and that’s not to say there weren’t detractors of it,” Sally told me. “Were we surprised at the extent? I mean, sure.”

The New Trier Township area has long been home to so-called “Lakefront Liberals.” In 2020, 73 percent of the 36,025 votes cast in the presidential elections went to President Joe Biden and four years earlier, Hilary Clinton earned about 69 percent. In 2012, Barack Obama beat Mitt Romney by a thinner margin of 10 points. “But we do have a contingency of right-wingers that somehow slips into the landscape here,” Moy said.

Only a minority campaigned against Seminar Day in 2017, but theirs was a vocal dissent, spearheaded by some community members and amplified by their ties to statewide and national groups, and conservative writers and publications. Some of the dissenters had previously promoted “school choice” alternatives to the traditional public system, from charter schools to voucher programs used to pay for private and religious schooling, a cherished ideal of Trump’s Education Secretary Betsy DeVos. An op-ed in the Wall Street Journal by a Stanford Hoover Institution fellow carried the headline “It’s Racial Indoctrination Day at an Upscale Chicagoland School.” Another in The Hill by a former researcher with the climate science denialist conservative think tank Heartland Institute read “How left-wing and racist radicals are infiltrating our children’s minds.” The Wilmette-based online publication Wirepoints published several pieces critical of Seminar Day, including one accusing the school of “ripping its community apart.”

The other side offered some resistance to the outcry. On February 23, 2017, a few days before Seminar Day was scheduled to happen, Traynor, the Wilmette filmmaker, went on the PBS news program Chicago Tonight to debate Betsy Hart, who had by then become the public face of Parents of New Trier. A former Reagan administration spokesperson, Hart had worked as a senior development writer for the conservative Heritage Foundation where she helped “raise millions of dollars for the Heritage enterprise each year,” according to her LinkedIn profile.

“It comes from a place of critical race theory, which is a belief that all disparities between Blacks and whites are caused by systemic racism and that, therefore, the structures of society have to be rebuilt,” Hart said of Seminar Day. This likely was one of the first times the term “critical race theory”—an academic framework that understands racism as systemic to society—had been used in the context of high school education. It would be several years before Manhattan Institute Fellow Christopher Rufo would take credit for weaponizing it, Glenn Youngkin would declare war on it to win the Virginia governorship, and groups like Moms for Liberty would stoke a parental movement and school board takeovers around it.

New Trier High School.

Courtesy of Paul Traynor

Traynor wasn’t alone in publicly supporting the school. Susan Berger, a longtime journalist and a 1970 New Trier graduate whose three daughters also attended the high school, told CNN in 2017 that if there were any silver lining about the controversy, it was that “it got people thinking and it got people talking, and I think that’s always a good thing.” New Trier, Berger told me, has always been “cutting edge” in challenging students on social issues. She fondly remembers the first Black teacher at New Trier, the late Jaime McClendon, who started a summer seminar in community affairs there in 1965—the same year MLK delivered a memorable speech about housing discrimination before 8,000 people in Winnetka. Local kids visited City Council, sat in juvenile court, and engaged with social agency officials. It became an opportunity for New Trier students to mix with kids of different backgrounds from inner-city Chicago schools.

After being hired at New Trier, McClendon bought a house for his family in Glencoe, just north of Winnetka, the neighboring village where the first Black man to purchase a home in the 20th century did so in 1967. Berger recalls in a Chicago Tribune column that his moving to the neighborhood caused an uproar among white residents. McClendon, Berger told me, is the reason she became a journalist. Looking back at the 2017 controversy and “now with CRT and people wanting to ban books and all the backlash about teaching about racism,” she said, “I think it was the seeds of all this polarization taking hold.”

What happened in New Trier, Adrienne Dixson, a professor of education policy, organization, and leadership at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, says, was a precursor, but not an anomaly in light of the long history of white people protesting multicultural and inclusive efforts. “We only have to go back to when schools were trying to desegregate,” she says. And the fact that it happened in a wealthy liberal suburb of Chicago, serves as “a reminder of the reminiscence of racial antagonism” in the country.

On February 28, 2017, Seminar Day took place on both of New Trier’s campuses: the one in Winnetka for sophomores, juniors, and seniors, and the other in Northfield for the freshmen. In total, 3,095 students were present, an attendance rate of almost 77 percent compared to 60 percent the year prior. A post-event survey conducted by the school with staff and students generated 1,650 responses reporting, overall, a positive experience. The majority, according to a memo shared by the school, “felt that discussions of race at New Trier are important and should continue.” Only about 5 percent of students surveyed said they didn’t enjoy the event, with some arguing other viewpoints should have been presented.

But that wasn’t the end of it. Administrators chose not to organize a similar program the following year, a decision some of those who had opposed the event in the first place considered to be a victory. The school disputes the argument that the reason was the controversy, however, instead clarifying that those events were never intended to happen on an annual basis or focus exclusively on race. In 2018, students still would discuss Dr. King’s legacy during extended advisor room periods, and a new Civics and Social Justice class was introduced. The intention was to “de-couple Seminar Day, which is simply one structure for focusing discussion on an important topic, from our continuing examination of race,” Dizon, the school district’s director of communications, says, With or without Seminar Day, New Trier does “not want discussions of race, identity, and belonging to take place only on one day a year and instead want these goals to be part of our everyday mission.”

Between late 2017 and the spring of 2018, offensive graffiti repeatedly appeared in New Trier’s bathroom stalls. The school’s stated commitment to racial equity was put to the test. In May 2018, the school engaged the community in the creation of a ten-year, multipart strategic plan that included “culture, climate, and equity” as a priority, which the school board adopted the following year. The racist graffiti also led some parents, students, and teachers to create Healing Everyday Racism in Our Schools (HEROS), a group that works with school administrations to implement a more diverse workforce, an anti-racism curriculum, and train a student bias response team. When our students graduate,” Superintendent Sally says, “we want them as prepared as they can be for a more diverse world and community that they will probably be moving into.”

Still, Sally acknowledges that there’s work to be done. In 2020, a few days after George Floyd’s death sparked a nationwide racial justice movement, a viral video resurfaced of a New Trier student using a racial slur. Students demanded the school bring back Seminar Day, and Sally recorded a message addressing the video. “We are both sad and hopeful,” Sally said. “We’re sad because of the fear, injustice, and racism that our students and staff of color, along with their families, experience every day just trying to go about their daily lives…Many of you have shared your pain and anger at experiences you have had at New Trier and I want you to know, we hear you, we want to do better, and we will do better.” That June, an Instagram account called “untoldnewtrier” started posting anonymous testimonies from students of color about their experiences with racism and discrimination.

The school’s doubling down on anti-racist practices spurred reactions from critics. Two days after Sally’s message, members of the New Trier Neighbors group—a new iteration of the original 2017 group that opposed seminar day—submitted a statement to be read at a scheduled school board meeting, communications obtained by Mother Jones via a public records request show. The email was signed by one of the members, Beth Feeley, and praised the school for focusing its response on “personal accountability” and not “cancel culture.” But it also expressed concern over the “equity agenda” based on the “highly controversial notion of critical race theory.” The school board, the group suggested, should concentrate less on “how we here in our leafy suburbs can focus on and apologize for our privilege” and more on practical ideas to uplift low-income neighborhoods. “When New Trier administrators decide that some thoughts are more equal than others they are doing a disservice to the families they supposedly serve,” the statement concluded.

For Feeley, the New Trier Seminar Day had marked the beginning of her activism. “I was a parent [of a freshman] and I noticed some things happening at my children’s school that I thought were highly questionable,” she said on the Take Back Our Schools podcast by the conservative Ricochet Audio Network in March 2022. Feeley is now a senior adviser to the Washington, DC-based nonprofit Woodson Center where she helped launch 1776 Unites, a conservative response to the New York Times’ groundbreaking 1619 Project. She is now the cohost of the podcast—which brands itself as putting the listener “on the front lines of the culture wars”—with Andrew Gutmann, a New York City parent who pulled his daughter out of the all-girls, prestigious Brearley School last year because of their “obsession with race.” Looking back at the events at New Trier, Feeley explains that at the time, hot-button terms like CRT and social-emotional learning were “not in the public eye. It was an eye-opening experience…It was definitely a trial by fire.”

The backlash that began in New Trier foreshadowed local conflicts in states across the country. Researchers with UCLA’s Institute for Democracy, Education, and Access found that almost 900 school districts with as many as 17,743,850 students—or 35 percent of all K-12 students in the country—have been affected by anti-CRT efforts. They describe a national campaign enabled by local critics and a “vocal minority” as “many local wildfires, one fire.”

In Illinois, attempts to pass “curriculum transparency” and anti-CRT laws have stalled. But parent activists and groups like New Trier Neighbors have remained steadfast in their crusade and what started as opposition to Seminar Day has metastasized to include other issues. In its newsletters, New Trier Neighbors denounce a wide range of what they perceive to be radical leftist ideology, including “gender theory” supposedly being taught in schools through books like It Feels Good to be Yourself: A Book About Gender Identity. In March 2021, Feeley wrote an op-ed for the Chicago Tribune decrying proposed legislation introduced in the Illinois General Assembly that laid out a list of required reading for elementary and secondary schools. Included were nonfiction and fiction books about racism such as Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates, James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time, and The Bluest Eye, by Toni Morrison. The answer, she proposed in the article, was for parents to “opt your child out of lessons that violate your family’s values,” connect with other parents, attend school board meetings and run for school board seats.

In May 2021, New Trier Neighbors joined like-minded organizations such as Moms for Liberty and Parents Defending Education in signing a letter criticizing aspects of a Department of Education’s American History and Civics Education programs grant that had as one priority to “incorporate racially, ethnically, culturally, and linguistically diverse perspectives into teaching and learning.” Specifically, they objected to the mention of the New York Times‘ 1619 Project and author Ibram X. Kendi in the request for applications, writing that “under the auspices of this grant program, discrimination will be introduced into classrooms across the country.” The pushback prompted Education Secretary Miguel Cardona to explain it would “not dictate or recommend specific curriculum be introduced or taught in classrooms.”

Soon after, another issue galvanized some parents at New Trier, this time about Two Boys Kissing, a 2013 young adult novel long-listed for the National Book Award that was optional reading at the time but has since become required for sophomore honors English classes. At the school board meeting, parents who deemed it to be inappropriate objected to “profanity, sex, and underage drinking” and “soft porn” content. School board members and administrators replied that it was their duty to make sure students can recognize their identities in the curriculum. According to the local publication the Record North Shore, the pushback followed a mass email sent by New Trier Neighbors saying “Is it time to start reading at New Trier school board meetings the materials they assign to our kids?”

The group has also taken aim at the Keeping Youth Safe and Healthy Act signed by Democratic Gov. J. B. Pritzker in August 2021 instructing schools to adopt comprehensive sex education standards. Republican gubernatorial candidate and State Senator Darren Bailey called the legislation “obscene.” Most school districts have rejected the curriculum in what the Chicago Tribune described as the “latest battleground in education culture wars.” The New Trier Neighbors charged that the standards were a kind of Trojan horse, containing progressive views of reproductive, social, and racial justice, and equity. More recently, they have taken issue with the school’s affinity groups and an identity project based on social-emotional learning. The group didn’t respond to an email with detailed questions.

The last few years have only intensified what began in 2017 and yet, unlike many school districts across the country, the New Trier school board has not been riven by internal conflict from extreme members. Leslie Weyhrich, the mother of three New Trier graduates, says the school district has been under continued attack over mask mandates, LGBTQ issues, social-emotional learning, CRT, and curriculum. “They thought we were conspiracy theorists and look at the state of things now,” she told me. Weyhrich is a member of New Trier Local, a group of concerned parents sharing information about “highly politicized outside influence” on local issues and exposing attempts to “bring the culture wars into our schools.” Starting in 2021, the group sent around regular updates about local school board elections, successfully supporting progressive candidates who were running against conservative candidates. The real test of their effectiveness may come next spring, when three New Trier school board seats out of seven will be on the ballot. “New Trier has been able to keep these right-wing zealots off of our local school boards and other local bodies by exposing their stealth candidacies and making their connections known to the residents of our area who reject their politics and ideology,” says Weyhrich. “It’s a real David and Goliath story.”

Traynor describes the experience of trying to stop these forces as “facing a fire hose and using a squirt gun.” So far, the squirt gun seems to be winning. It takes an active and vigilant community, Traynor says, to fend off these advances and it’s “more time and energy than most parents have.” For Beth Feeley, however, the fight will continue and is gaining momentum. She points to a growing mail list with around 2,000 subscribers and how battles like the one she fought years ago at New Trier have expanded. “I’ve had friends say to me, now I understand what you had a problem with all those years ago,” she said on the Take Back Our Schools podcast. “It’s been kind of satisfying to not be that lone voice in the wilderness anymore.”