It is a brisk April evening in downtown Minneapolis. A haphazard crowd of about 20 people gathers. Some carry American flags. A homily from the mid-20th century Catholic archbishop Fulton Sheen—famous for bringing the Word of the Lord to TV and radio—plays through loudspeakers. The plan is a protest, to march and to stop traffic. And so the group begins walking behind a flatbed truck that crawls down 1st Street, running parallel to the Mississippi River. Now, “The Star-Spangled Banner” and “My Country, ‘Tis of Thee” play through the speakers. A woman, with “Arrest Fauci” written in black marker on duct tape attached to her hat, smokes a cigarette as she walks.

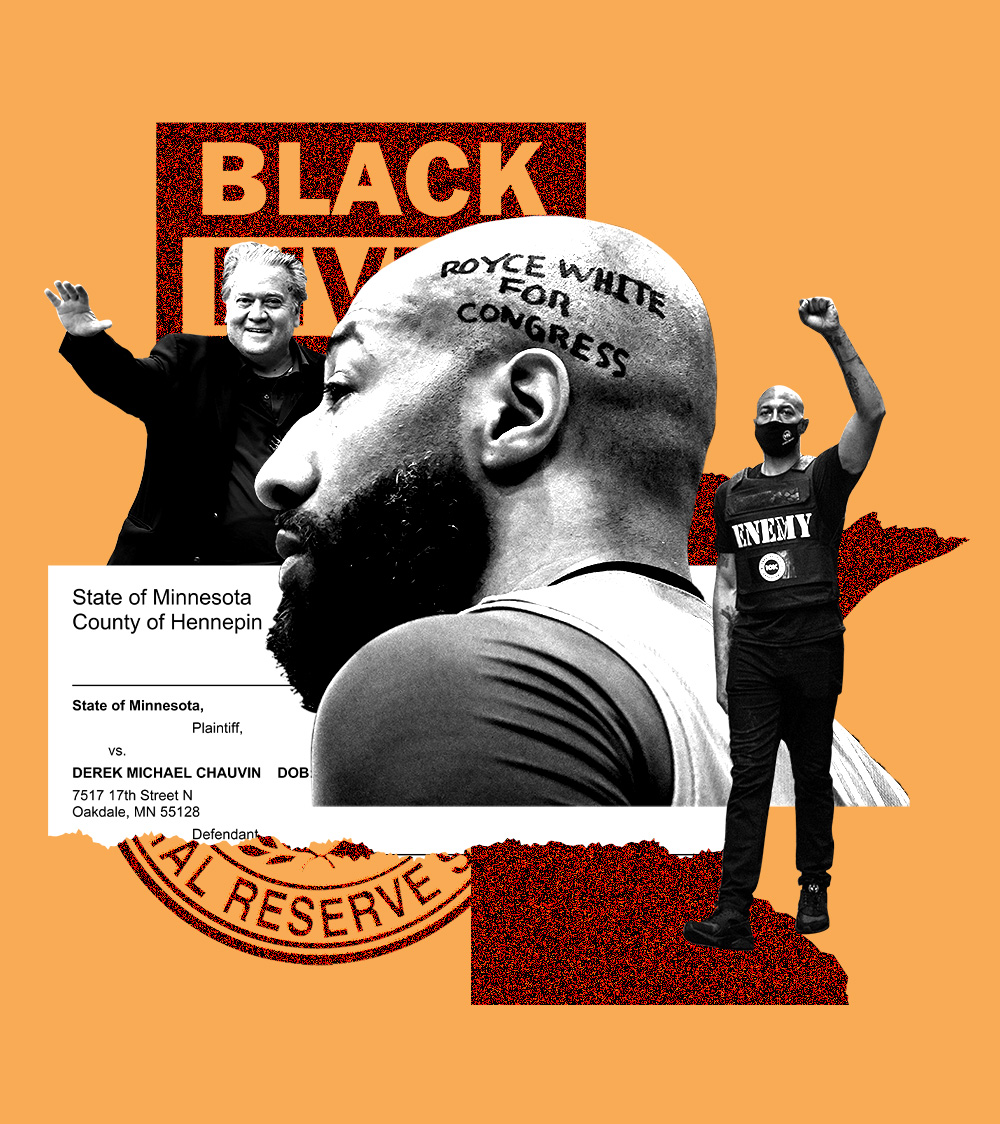

This is a campaign rally for Royce White, a Republican who was encouraged to run for Congress by Steve Bannon; an activist who led Black Lives Matter protests; and a famous one-time NBA first-round draft pick. Affable and charismatic, White—6 foot 8, bald and bearded—walks among his few supporters and rubs his hands together incessantly. It is April, and winter is lagging in Minnesota, and so maybe White is trying to warm up. Or perhaps he is nervous about the paltry turnout for a campaign he has called a revolution.

In February, Royce White announced his candidacy for the District 5 seat with a warning: “A storm is brewing.” In a 3,500-plus word Substack post, he outlined his realignment to the America First far right. White described a God-driven but vague encounter with Truth over the past two years that led him to realize that Black men were being abused by the Democrats, and that Republicans would be a better alternative. While the post spent significant space batting away potential criticisms (“Royce White Owes Child Support,” “Royce White Has Debt,” “Royce White Is Afraid to Fly”), White’s campaign is primarily focused on calling for a mass exodus from the Democrats. “I’m a populist,” he wrote, “and we are leaving the plantation.”

In his born-again-Republican origin story, White says he was cast into the political wilderness after the NBA refused to meet his demand for better mental health policies. (He calls it his first run-in with globalism.) In 2020, he reemerged as one of the voices of the Black Lives Matter movement in Minneapolis after the murder of George Floyd set off national protests. As Royce stood on a bridge overlooking the Mississippi River, he told a reporter the protest gave “that feeling of Selma back in the ’60s.” The Washington Post described him as “one of the freshest emerging leaders in this new civil rights moment.” He’s since rejected BLM because, he says, the movement prefers Black men to be “dead, gay, sold out, or on the wrong end of sexual harassment, or Me Too allegations.”

His current politics could be described as tinfoil hat populism. He believes that the Democrats, Bill Gates, the World Economic Forum, President Xi Jinping, the CCP, non-MAGA Republicans, George Soros, “millennial purple-haired white liberal women,” “the Church of LGBTQ,” the National Basketball Association, and various government agencies all act on behalf of the same “global corporate community.”

This evening, the destination for the marchers who have gathered is the local headquarters of the Federal Reserve. White holds a special animus against the US central bank, believing that it has disempowered average Americans by helping accrue over $30 trillion in national debt. Using rhetoric that sums up his political approach as a Republican, Royce has repackaged banal conservative deficit hawkery as original, rebellious, and compelling for voters. It is an approach he may have learned from his mentor, Steve Bannon.

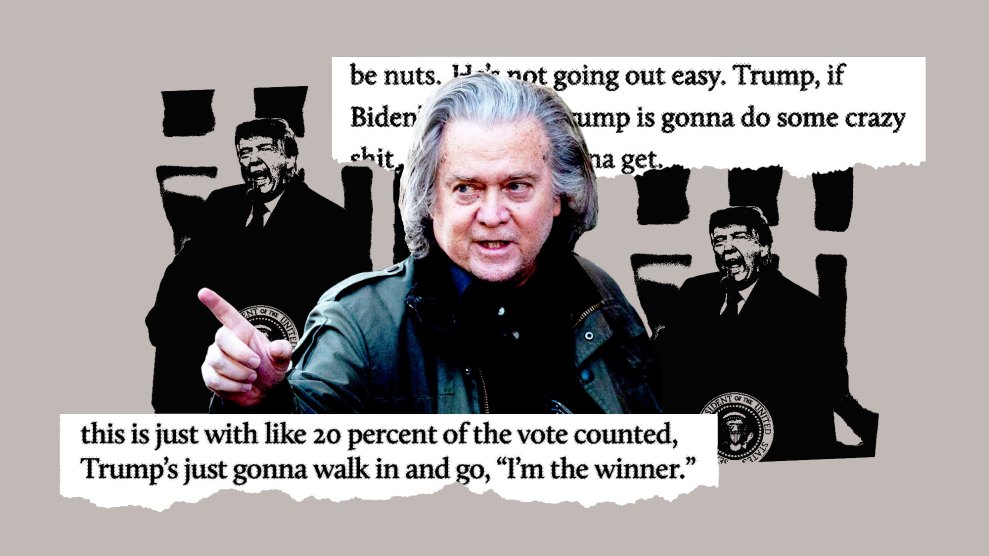

The recently convicted former Trump consigliere is the man perhaps most responsible for White’s transformation. Sometime during the summer of 2021, according to the Washington Post, White was introduced to Bannon through the Big 3, an upstart three-on-three basketball league populated by ex-NBA players, among others. The league was founded by the rapper and actor Ice Cube and Bannon’s longtime friend, Hollywood mogul Jeff Kwatinetz. As White told Alex Jones in a recent in-studio appearance on Infowars, he would not have joined the MAGA movement without Bannon. For White, Bannon is a mentor, friend, and “American hero.”

It was Bannon who told White to run for the GOP nomination for Congress in Rep. Ilhan Omar’s district, which Democrats routinely win by over 20 points. In the August 9 Republican primary, White will face a candidate named Cicely Davis. She handily won the state party’s endorsement and is considered the favorite. But winning might be beside the point.

A Minnesota-based GOP strategist told me that Bannon likely was looking for someone who could raise money and embrace the “Stop the Steal” cause. In September 2021, ProPublica reported that Bannon had effectively mobilized thousands of his listeners to get involved in electoral politics on the state, county, and local levels. Royce White, as much as anyone, embodies Bannon’s dream of mobilizing his podcast audience to be the grassroots champions of the stolen election myth. “You come from a place [where] you have the bonafides to speak truth to the power,” Bannon told White in an in-studio interview in March 2022. “When you first got started in the George Floyd situation, MSNBC—you were like the poster child. They couldn’t get enough of [you].” Now, as Bannon recently gushed, White is “harder right than I am.”

Bannon’s former colleague Andrew Breitbart was known to say, “Politics is downstream from culture.” For Bannon, making Royce White a star and “the future of the Republican Party” might be more important than a seat in the House. White possesses incredible symbolic potential as a professional athlete, a Black man who once was a leader in Black Lives Matter protests, and someone willing to do anything to get his message out.

Over the past year, his media credentials have blossomed. White recently co-hosted an episode of the War Room alongside Bannon. He contributes to sportswriter Jason Whitlock’s show on The Blaze, Glenn Beck’s network. In the midst of being on the receiving end of lawsuits for calling victims in the Sandy Hook massacre “crisis actors,” Alex Jones invited White to guest-host a segment of his Infowars broadcast. White has made several in-studio trips to see Tim Pool, the disaffected former Occupy Wall Street livestreamer turned one of YouTube’s favorite reactionary pedants. On Tucker Carlson’s show, White made a short but well-received appearance in which he argued the “uniparty” sold a “fantasy of globalism—which is just another way to attack the American working class.” Soon, White plans to launch his own podcast.

Watching White’s campaign rally, I began to wonder if this was less a start of an electoral push than a crucial first step in his new and viable career as right-wing media provocateur. It feels like a prank, as I watch Jonathan Mason, White’s campaign manager and the brother of a former basketball teammate, standing on the flatbed of the truck, yelling for more civil disobedience: “When Black Lives Matter protests, they just take up the road. We’ve got to do the same thing. People will catch on. Patriots will catch on.”

But the attempt to take over 1st Street fails. Motorists are irritated. Horns are honked. The patriots settle for the bike lane.

I grew up in Minneapolis and played high school basketball during the same years as White. He’s considered, with good reason, to be one of the best players ever to come out of Minnesota. Growing up in different parts of the Twin Cities metro area, White split time living with his mother, his grandfather, and other relatives. While his single mom was at work as an esthetician, Royce would practice basketball for hours at local rec centers, as he told Bannon in his first in-studio War Room appearance. “That discipline,” Bannon replied, is what he looks for. “[It] goes through all of life.”

White chose to stay in the state and attend the University of Minnesota. Local fans were jubilant. But the excitement didn’t last long. His first year, Minnesota Gophers coach Tubby Smith suspended White for two separate but unrelated off-the-court incidents. Even then, White showed a desire to control his own narrative, and a penchant for media stunts. Before he had formally requested to withdraw from the university, he released YouTube videos. In one titled “Royce White: The Last Interview,” he announced he was leaving the program. He found refuge at Iowa State University, where he led his team in all five major statistical categories and starred in an NCAA tournament matchup with future NBA superstar Anthony Davis.

Royce White was a star basketball player at Iowa State in college.

Damian Strohmeyer/Sports Illustrated/Getty

White was selected by the Houston Rockets as the 16th overall pick in the 2012 NBA Draft. He had point-guard skills in a power forward’s body, drawing comparisons to LeBron James. But even as a college kid thrust into the spotlight, he was a “mystery,” according to media reports, because he had the confidence to speak out about a taboo issue. White refused to play ball until the Rockets agreed to treat his generalized anxiety disorder with the same support they’d treat a rolled ankle. Houston and the NBA weren’t interested. White sat out. And he lost millions. His only appearances in the NBA, according to Basketball Reference, came in 2014 when he played a total of nine regulation minutes with the Sacramento Kings.

At the time, I remember admiring White’s prescient stance on mental health in sports. His struggle became one of the rare warnings, before Simone Biles and Naomi Osaka, that athletes were actual people. (After the NBA player Kevin Love publicly shared that he struggled with anxiety, he gave White a shout-out.)

His story with the NBA was catnip for some journalists, myself included. White and I had lunch in Minneapolis sometime in 2016, and I’d later interview him over email. Here was a young Black man who called out a professional sports league as an exploitative “human commodity business,” and was willing to pay the price with his career. In 2013, Dave Zirin, Sports Editor of The Nation, called White a “mental health revolutionary,” and placed him in the tradition of trailblazing athlete-activists like Billie Jean King, Bill Russell, and Muhammad Ali. (Zirin declined to comment.) In a profile covering White’s post-NBA career playing professionally in Canada for the London Lightning of Ontario, Esquire described him as “the most important basketball player alive.” In another profile, a writer likened White to light itself.

I saw White again in 2016, at a St. Paul library, during the height of the public frenzy over another athlete who had paid for their principles with their career. White and Zirin held a public conversation on what San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick’s taking a knee would mean for athlete activism. I had recently graduated college at the time and sat next to my sociology professor Doug Hartmann, a specialist in the intersection of sport, race and athlete activism.

When I spoke to Hartmann earlier this summer, he was still wrapping his head around White’s flip. “What’s super uncomfortable for me now is that with this right-wing shift, is that it’s hard to figure out: where’s the coherence at all,” he said. “It’s really hard to see the continuity between some of the things he was talking about previously, and what he’s talking about now.”

In 2020, Royce White made headlines again. He had never protested before, but in the wake of George Floyd’s murder by Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin on a street corner in south Minneapolis, White sent a text to a group chat of fellow Twin Cities athletes. Together they called themselves the 10K Foundation, and they banded together to show the power of peaceful protest.

A flashy website followed with striking photography, press releases breathlessly recounting each protest, an online store selling apparel to “gear up for the revolution,” and an open letter from White to Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz, which now reads like a less scorched-earth version of his Substack screeds. Their lack of experience quickly became apparent. As one of the protests took over the 35W interstate highway bridge, an oil tanker truck drove through the crowd and nearly ran over participants. The episode made more veteran activists wary of the 10K Foundation, whose members included the now vice president of the Minneapolis NAACP, P.J. Hill. (Hill declined to comment for this article, citing the NAACP’s neutral stance in elections.)

White took center stage as Minneapolis became ground zero in a nationwide outpouring of outrage at police killings of Black men. Reporters and news producers from both local and national media grasped for a coherent narrative from the unrest. They flocked to the ex-NBA player who was putting it all on the line for his politics and likened him to Kaepernick. In a televised interview with CNN on June 2, 2020 White said Kaepernick’s protest was “definitely prophetic,” and that “there’s no stronger symbolism in our time right now for protests than what he has already laid the groundwork for.” He noted that his mental health protest with the NBA, “was just as prophetic as what Colin Kaepernick did.”

In interviews and social media posts at the time, White’s views seemed relatively consistent with those from many people taking to the streets in Minneapolis and across America: Derek Chauvin was a murderer and the country must change. In an interview on Zirin’s Edge of Sports podcast, White called Donald Trump a fool whom he’d never have let sit at his lunch table. He did not condemn looting and property destruction. “The looters are a response of a lack of justice,” he told the Des Moines Register. If the police continued to escalate, he threatened a return to the militant, armed self-defense of the Black Panther Party. He retweeted a call to dismantle the Minneapolis Police Department.

“When George Floyd was killed, [White] was…being a good human being and standing up for what he believed at that time,” said Toshira Garraway, the founder of the group Families Supporting Families Against Police Violence, a Twin Cities–based organization that supports the families and loved ones of victims of police violence. “He always treated me with respect. He always treated the other families with respect.”

Signs that White might not follow a conventional activist trajectory wouldn’t surface publicly until the following year. In April 2021, the Twin Cities underwent another moment of racist police violence just as Chauvin’s murder trial was underway. In a suburb just outside of Minneapolis, a cop named Kim Potter shot and killed a Black man named Daunte Wright after she pulled him over. Potter says she was reaching for her taser. In February, she was sentenced to 16 months in prison for first- and second-degree manslaughter.

Protesters, including White, and other members of the 10K Foundation, gathered outside of the Brooklyn Center police station, where Potter worked. The facility had been surrounded by a large fence, which White said represented “tyranny.” He called for the crowd to join him in breaching it. An argument between White and other protesters ensued, and the aftermath was captured on video.

“Black men will lead the revolution. 18-year-old Black girls who identify as this or that will not lead the revolution,” White yelled into a megaphone. Facing accusations of misogyny, homophobia, and transphobia, White became more belligerent in Instagram live videos.

The 10K Foundation has announced few events since. Prominent members, including the co-founder Tayo Daniel, did not return repeated requests for comment.

A few days after his meltdown, White appeared with Rachel Maddow on MSNBC as a representative of the movement to discuss the guilty verdict in Chauvin’s trial. “We’ve been watching this trial with great interest and heavy hearts with George Floyd and his family,” he told Maddow. “We hope today’s verdict gives them some peace and that it serves as some legal precedent as we move forward.”

“The people view America as a corporation,” he continued, “and they view our police departments as corporate assets.”

In the summer of 2020, White played a leading role in organizing protests after the killing of George Floyd.

Stephen Maturen/Getty

Viewers couldn’t have guessed White was in the midst of a fallout with the movement while on Maddow. But perhaps they could have seen that Royce wasn’t a typical voice of the left, even then. BLM Royce and MAGA Royce may have parted, but the vaguely libertarian, anti-authoritarian language remains the same: tyranny, sovereignty, corporate overlords, all conspiring to damage the free people of America.

Later, White would admit he had been tuning into the War Room months before the protests started. When the pandemic hit the US in March 2020, Bannon was pumping out anti-China Covid conspiracy theories. White listened. He then repurposed some of the same arguments for his BLM talking points. He took on the right’s dislike of globalism, too. (He even led a BLM protest to the Fed building.)

Protests bring many people for many reasons. But media needed someone to speak for the masses. White took on that responsibility, even if his views were always unusual.

“Unfortunately we as an organization have nothing positive to say about Royce,” one local activist group, which had organized an event with Royce and 10K, wrote me. “There’s been a lot of harm caused by his actions.”

Starting in April, I tried to speak with White about his campaign and his political evolution. We developed a pattern: First, he and Mason agreed to an interview. Then, they ignored my messages. Then they bailed on our interview. Interspersed with these communications would be direct messages to me on Instagram with copy-pasted requests to share information about his campaign and media appearances. I’d respond by asking to sit down for an interview, reminding them they had told me Royce would talk. Sometimes there would be a response. Then, no follow up until a few days later, when I’d receive another template Instagram DM.

I turned to someone who has known Royce his entire life to get a better sense of him. Frank White, Royce’s grandfather, is an elder statesman in the Minnesota sporting scene. He coordinates a program to revive baseball in the inner city and as a historian of Black sports in the state, he’s currently working on his second book. This one is about athletes from the Rondo neighborhood, a historically Black area of St. Paul that, like many historically Black neighborhoods, was upended and displaced by the construction of the national highway system.

Royce lived with Frank from 8th grade until his senior year of high school. “During that stretch of time, I was dad and grandpa, at the same time, and went to all of his games,” Frank told me.

“I’m proud of my grandson, but do I agree with his politics? No,” he said as we spoke on the phone. “He told me, ‘Hey grandpa, I’m going to be on Steve Bannon’s podcast.’ I said, ‘Do you know who Steve Bannon is, man?’” (When I called Frank for a follow-up recently, Steve Bannon had just been found guilty of contempt of Congress. Frank said he’d spoken to Royce and told him, “Your guy Steve Bannon is probably gonna go to jail.”)

What about the fact that Royce was championing the stolen 2020 election myth and the Capitol riot and attempted coup on January 6?

“There’s no way I can support my grandson supporting the GOP, and in essence, Trump. This is a guy who wants to be a dictator. Think about what that means,” said Frank. “You’re a person of color. Do you think you fit in his plans?”

Royce, of course, does think he fits in. The standard Black conservative line is that Democrats are just a few election cycles of broken promises and legislative inaction away from losing a significant share of Black votes. Given how the modern-day GOP has so many ties to institutional white supremacy, and continues to scapegoat Black Americans, the Black vote fleeing to this party seems implausible. But there is truth to the argument that Democrats assume Black voters will elect them without meeting their needs, and have an over-reliance on “Republicans are more racist” in lieu of a campaign strategy.

“I’m not afraid that Royce will be that guy,” said Dr. Jason Nichols, a lecturer in the African American studies department at the University of Maryland, College Park, of this push for a voice for Black conservatives. “But I’m afraid that that guy is coming.” Republicans wouldn’t have to win over that many Black voters to make a serious dent in Democrats’ electoral prospects, he said, they’d just have to peel away enough of a margin in certain locales.

“[The right is] is winning the culture war because they’re saying, ‘This is against your Christianity, this is against your manhood; things that are fundamental to you,’” he noted. “And implicitly, ‘It’s against your Blackness.’”

Nichols thinks the Democrats should be hitting the “panic button” upon seeing all of this. “If [Royce White] can be convinced that quickly—you know, George [Floyd’s] murder is only two years ago—it makes me think [as a Democrat]: What am I not messaging well enough?” he said. “If you asked [Democratic] strategists about Royce, they’d be like, ‘Who’s that? Who cares?’ But I’m like: ‘You should care.’”

Frank White surely cares. He still holds out hope.

“I wish Royce would turn the page because he has the heart to change people’s lives, if it was in a different fashion,” Frank said. Then pausing, he reflected on the effects his new celebrity, his new political allegiances, and his new crusade might have on his charismatic, talented, and sometimes troubled grandson. “I do fear that it’s gonna have an impact on his life different from what he might believe.”

In early June, White bought a billboard in downtown Minneapolis, right across the street from the Target Center, where the Minnesota Timberwolves play. A side profile shows “The United States of the Federal Reserve” written in big black letters across his head. The billboard has his official campaign slogan that sums up his refusal to compromise that has spanned his various causes: “No Lockdowns. No Mandates. No Apologies. No Sellin’ Out.”

“Nobody is ever quite good enough for Royce,” Doug Hartmann, my old professor, who spent hours interviewing Royce about politics and activism in the summer of 2020, explained, noting that Royce believed the NBA protests that summer were insufficient. “He likes stirring the pot. I don’t know that he has a lot of commitments to particular texts or core ideas, so much as a [commitment] to the free flowing, brawling nature of political debate.”

This sensibility fits comfortably in the right-wing media ecosystem, if not in a campaign determined to win. I watched a stream of his town-hall campaign event in Minneapolis on the right-wing Twitter-alternative Gettr. White repeatedly evoked the memory of George Floyd. One time he even argued that the Biden administration’s announcement of a crackdown on domestic extremism was lining up “each and everyone in this room to become George Floyd.”

But exactly how Royce now feels about Floyd’s death, and Chauvin, is unclear.

White has hired a Minneapolis attorney named Nicholas Morgan as his campaign treasurer. The law firm where Morgan works is called Mohrman, Kaardal & Erickson. (It shares the same downtown Minneapolis address with campaign headquarters.) One of the partners at the firm, William Mohrman, is currently working as a defense attorney for Chauvin as he attempts to appeal his conviction for murdering Floyd. The law firm is crowdfunding for Chauvin’s defense on their website.

The 10k Foundation is still selling apparel celebrating Chauvin’s guilty verdict on their website. White now notes that Floyd had “The CCP drug,” a reference to fentanyl and China, in his system.

At the Fed building, White declares that “these people need history lessons.” Speeches from Dwight Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, and Martin Luther King Jr. blast out from the speakers at a volume that makes it nearly impossible to speak to other attendees. It is part performance art, part public nuisance. The woman whose hat calls for the imprisonment of Dr. Fauci gives a speech. It mentions the New World Order, FEMA Camps, the Great Reset, critical race theory, gene therapy vaccines, and transhumanism.

I catch up with White at the demonstration and ask what he considers the biggest challenge of his campaign. “No challenges. It’s gonna be smooth,” he replies. “Bring the truth to the people. Let them decide. That’s America.”

Top image credits: Quinn Harris/Getty; Win McNamee/Getty; Stephen Maturen/Getty