Where Do We Go From Here? is a series of stories that explore the future of abortion. It is a collaboration between Mother Jones and Rewire News Group. You can read the rest of the package here.

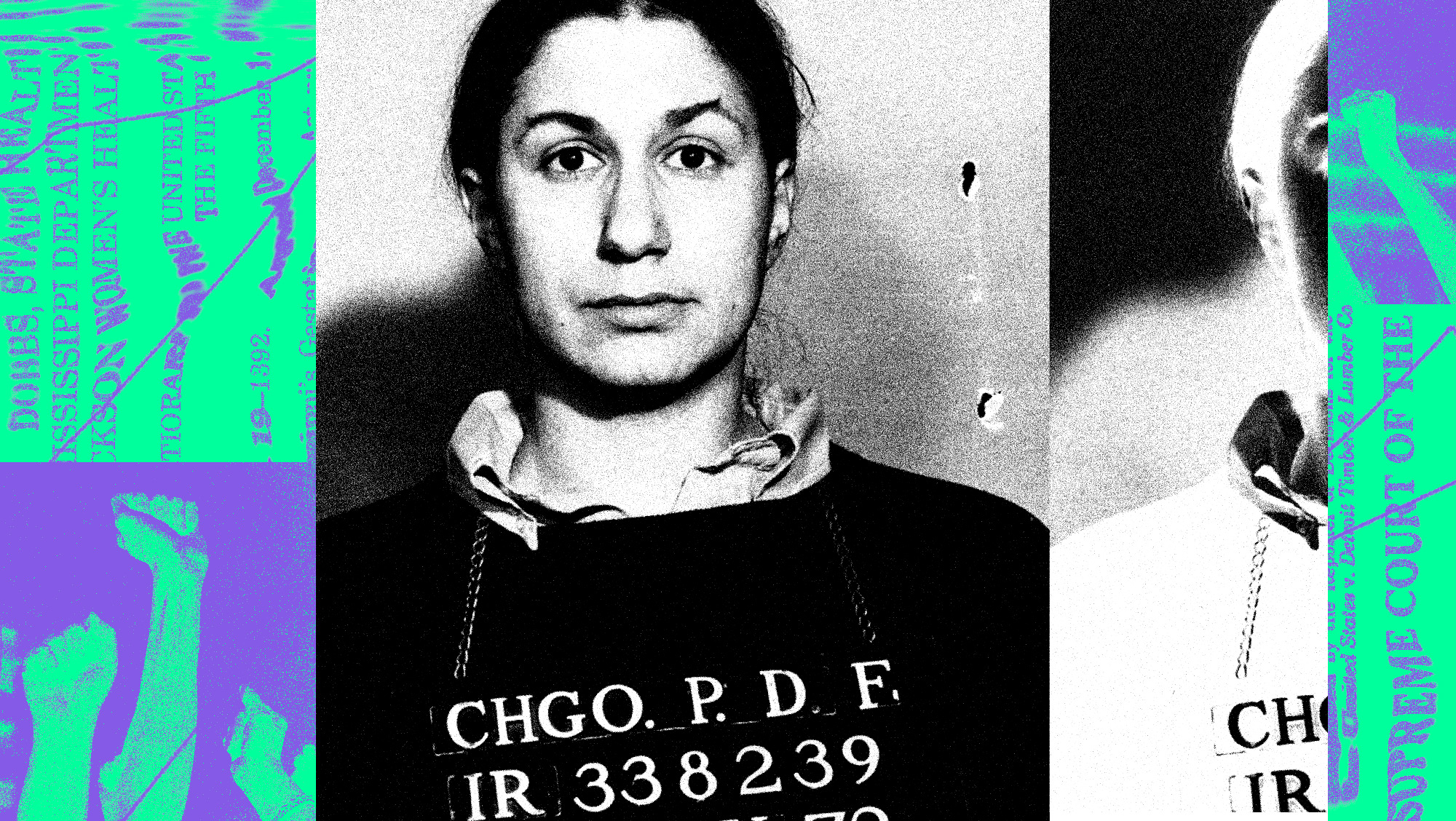

May 3, 1972. It was a spring day in Chicago and 29-year-old Judith Arcana was behind the wheel. She was driving patients who had sought abortion care from an underground abortion service that operated in Chicago by a group of women known simply as Janes in the late 1960s and early 1970s. If you found yourself pregnant—and you didn’t want to be—you could “call Jane,” and Jane would help you get the care you need. The Janes performed nearly 11,000 abortions during their tenure, without incident. But Arcana was a criminal. A felon. And she recognized it. But she didn’t care.

Providing abortion care to people was a matter of principle.

She had picked up several women from “The Front” (which was where the Janes provided counseling to the pregnant people who used their service) and was driving them to “The Place” (the location where other Janes would perform the procedure), which was constantly moving to evade law enforcement.

By the end of that day, she and six other Janes would find themselves in prison, ultimately facing 110 years in prison for conspiracy to commit abortion.

That’s 110 years each.

But still she didn’t waiver.

Arcana’s is a tale of bravery and of solidarity. Of refusing to leave her fellow Janes behind, even as her privilege and special circumstances led her to be the first Jane released from prison in the early morning of May 4, 1972—but only after she asked the other six if it was OK.

“GO!” they told her.

Arcana’s is also a tale of lawlessness—of a group of young women who saw a need that needed to be met and decided to come together to meet it, damn the consequences.

I think about the level of commitment to community it must take to undertake a criminal enterprise and to place your individual trust in the whole. Over the last 30 years, the group of women came to be known as the Jane Collective—a name several Janes eschewed, but which nevertheless stuck. The Janes simply called their operation “the service,” short for the Abortion Counseling Service of the Chicago Women’s Liberation Union.

To hear Arcana tell it, the word collective didn’t apply: They were so busy trying to run the service that they did not run or act as a collective. Meaning there was no effort to make the service’s internal political structure suit the idea of collectivity. They were simply a group of young women trying to provide a much needed service to pregnant people in Chicago.

Their disdain for the moniker notwithstanding, the term collective is powerful when applied to this brave group of women. You’re not just a Jane. You’re part of a group—a collective.

I first met Arcana four years ago in Austin, Texas. Yes, Texas: Ground zero for abortion politics. I was moderating a panel at SXSW ironically entitled “If Roe Were to Go.” I was blown away by her level of commitment to abortion access and was thrilled to be talking to her. I excitedly said to her, “So you were a Jane—.”

“Are a Jane,” she corrected me with a sparkle in her eye.

Even 50 years later, being part of this service—this collective, if I may—means something to her. Once a Jane, always a Jane.

At that same panel, I asked everyone to close their eyes and then I asked who would be willing to break the law if it came to that. A lot of hands shot up. But this was 2018. It was before Brett Kavanaugh. There was still a chance that Roe could be saved.

But Roe v. Wade was not saved. And now I think about what “collective” could mean in 2022.

There is a level of defiance rippling throughout the country among people who are long-time activists and advocates, as well as those who have recently been radicalized by six unelected people telling them that they are not considered full and equal citizens in this country.

The frustration is palpable. The pain is real. And many abortion rights advocates are facing a reality so terrifying that we are just reacting. We aren’t thinking.

But we need to stop and think. We all need to be smarter in order to protect one another.

Ultimately this next fight is going to be about community. It’s going to be about who you trust and who trusts you. And how far you’re willing to go to protect someone who may need an abortion.

It’s worth noting that not everyone can be a Judith Arcana. Not everyone can be a Jody Howard or a Heather Booth, the two women who co-founded the service. But everyone can play a role in this fight just as integral as Arcana’s was to the fight in 1972.

But whatever role you decide to play, you’re of no help to anyone if you don’t play smart.

We live in an age of digital surveillance and influencer culture. It’s a dangerous mix. It means people who may be well-intentioned are using public statements about their willingness to commit a felony to grow their social media following. And to the extent those people are white, may not have the cultural trauma response that makes most Black and brown people fear interactions with law enforcement.

Judith Arcana is a woman who faced more than 110 years in prison on multiple counts of abortion and conspiracy to commit abortion. She was one of many women who were willing to put their freedom on the line to provide a much-needed service.

I spoke with her about her time in the service and the documentary The Janes, produced by her son Daniel Arcana and recently released on HBO Max. The interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

You were facing a 110-year sentence on multiple counts of conspiracy to commit abortion. When you thought about that, did you panic at all, or did you always feel like, “We’re going to get through this. They’re not going to throw seven 20-year-old white women in prison for 110 years. That’s absurd.” What was your thought process?

Well, I can’t claim it was a particularly brilliant thought process on my part. I don’t want to claim to know what was in the other Janes’ minds, even though we’ve talked about it, but I did not live in a consciousness that included fear of being busted or fear of going to jail.

I knew, because I’m not clueless, that that could happen, but it just was not in the front of mind. It wasn’t even in the middle of mind. And when we did get busted, we were stunned, as many, many people are when they’re arrested, even if they know that they’re guilty of whatever they’re being charged with. And the thing about the 110 years, that The Janes notes correctly in the film, that was not even a focal point for me.

So what was the focal point for you?

It was, “I’m going to have my child taken away from me. I’m going to no longer have the life I have been living.” I was 27 when I joined the service. So 29 when we got busted, and like I said, I can’t speak for the others, but it just wasn’t what was primary. I didn’t have fear on a frequent basis. I don’t even think I had fear until we were actually cracked. And then there were even physiological responses to the cold in the police van, to being handcuffed.

And they had these hooks or links on the walls, in their offices at the police station, and they literally hung up the people’s handcuffs. So I’m sitting there like this, which is, of course, true of every single person they ever brought in—not just us. With my arms like this, with my handcuffs attached by them to the walls. And it took at least an hour before this guy said, “Oh, here, I’m going to take those cuffs off.”

That seems a bit unnecessary.

Yeah. I actually couldn’t help wondering, “Do they do this on purpose to weaken your resolve and your personal strength?” I don’t know.

Can you talk more about your experiences being in jail—were you there the full night, or you were just there for a few hours?

Well, the seven of us who were actually Janes who were arrested when they finally sorted out the 40 or so people—we were in the precinct for what seemed like a million hours. Then we were in the women’s lockup…for a long time, and it was about 3 in the morning. The next bus was at 3 in the afternoon. And we had begun working that day, probably between 8 and 9 a.m. So it was a long day. And at the lockup, six of us were put into cells in pairs, a seventh was separated. I can’t remember why she was separated, but maybe it’s because they wouldn’t put three in a cell? I don’t know.

But anyway, at about 3 a.m., the woman who was the guard for our section of the lockup, came to the cell, and said that there were some lawyers waiting to talk with us. And that I was being asked to leave my cell and go talk with them.

At the time your husband was a lawyer, was he the one who came to see you?

He was a lawyer, but he was not one of those people. He was home with the baby. It was definitely the right choice. But anyway, there were these three guys, two of whom I knew, one of whom I had never seen before. The short story here is that they had this notion that because I was a nursing mother, I would be the most likely person to be released in night court—in the basement of the women’s lockup, they ran this night court.

And at first I was taken aback to be separated from the others. And these lawyers said, “How about it?” They wanted to take me down there right away. I was not going to do that. I said, “I need to ask the others.”

You didn’t want to leave them.

The lawyers were not happy. That was the least of my concerns, that those guys were not happy, but the guard—who was really OK, she treated us very decently—took me back to the cell. And then I shouted because that was what was going on in the lockup. There were women who were screaming, and it was very noisy all the time.

So I just screamed across to the tops of the cells [that] were open, so to speak. I think it was iron netting. And I said, “OK, here’s the deal. This is what they want. What do you think? Should I do it?” And they immediately said, “Do it, do it, go.” And two of the other women were mothers, and one of them said, “Go. I would do it if I could.” And that was really important for me to hear, because I was dragged thinking, “I’m being put in a special category here.” But as soon as they said, “Go,” I said, “OK, fine.”

And then once again, that wonderful guard came. She took me with them. They took me downstairs. And I think I say this in the movie or something like this—that not only was I a nursing mother, which was their ticket, but I was a white woman. I was married to a lawyer. I had a college education. They had all my records out there and I was indeed a very good choice to get special treatment, which then benefited the other six. And since the other six had said to me, “Go…”

They were probably thinking, “You got a baby at home. We’ll be OK for a night, maybe.”

Yeah. So the judge thought that was a good idea and I left. So I think I got home at about dawn.

I can’t claim a level of consciousness in those times that would allow for a serious alternate life plan. Although as one of the Janes, a woman named Madeline who was one of the seven, said in another doc that came out in 1995—a short documentary about the service—that she says something like we talked about, “Oh, if we were in jail, we would do education about what we had learned.” Which is so unrealistic.

I think she has a line, like not as realistic as, for instance, being raped, which would be much more likely than what we thought we might be doing in jail. And that’s a very heavy consideration. And she said this, as I say, when that was being made, which was in the mid-1990s.

So we weren’t really thinking about what would happen if we got busted. Not while I was doing it. I know it makes us sound like ditzes and we clearly were not, we were very serious. We were doing heavy shit, and we did it all week long, many, many weeks, but we didn’t go down that path.

I don’t think it makes you sound like ditzes at all. I think it makes you sound really resolved. I would imagine at some point there was a fear and you thought about it, and you faced your fear and you just said, “Fuck it. I have to do this.”

Let’s talk about Mike. The documentary features a man named who is only referred to as “Mike.” He performed the abortions on the patients but who wasn’t a doctor. And you all didn’t know he wasn’t a doctor at first.

The first thing that comes to my mind that I always want to say is that he was the best. He was unquestionably an excellent abortionist. He was very good to the women. And he treated us—in terms of co-workers when we were assisting in various ways—with respect, and it was so clear.

I think your response to the revelation that he wasn’t a doctor highlights that you’re a really special kind of person; when you found out that Mike wasn’t a doctor, you and many other of the Janes immediately thought, “We can do this shit ourselves.”

So can you just sort of talk about what your mindset was and why it was you took the path of, “Fuck it. We’ll do it live,” as opposed to, “Oh my God, what are we going to do? We don’t have a doctor.”

I can’t even tell you my exact mental steps—I probably wouldn’t even tell you the day after—but I was not the only one who felt that way. There were people who were already leaning on him big time. Janes were nagging him, “Teach us this, teach us this, teach us this.” And there were some people who were already beginning, the ones who were closer to him, the ones who picked him up at the airport and he stayed at their apartments, etc.

For me, personally, the idea that he was not a doctor was—what’s the best word to use here? God, I hate to use the word liberating, because it’s just so corny now, but…

Revelatory?

Yeah. Revelatory. I just thought, “Well, OK then.” Why wouldn’t we? So that was it.

Do you have any advice for someone who is radicalized, galvanized, thinking maybe they might be willing to break the law to help a friend or a stranger get an abortion?

I always like to say, even if you’re not the person that’s going to go bash a window or perform in an illegal abortion, you probably know someone who is willing. So I always say, go talk to them and maybe figure out how they got to the place where they were willing to bash a window or perform in an illegal abortion.

Well, I always try not to “give advice,” but I would say that it’s extremely valuable to think very seriously about the impact your actions are having on other people and the neighborhood or the environment, however far out you want to talk about impact.

Even though much of what we did literally sprang out of us because of the need for the service, it’s not true that we didn’t seriously think about it and talk about it. We did; often in one-on-one conversations with the people who were our friends. We weren’t all friends, some of us barely knew each other, because that wasn’t necessary, to be friends to do what we were doing.

But if you are lucky enough to have conversations with people who are seriously thinking, “OK, what if we set up a service in which we did this, how would that work? What would that mean? What would the risks be, etc.” Yes, that would be very, very good.