This story was produced by Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting. Get their investigations emailed to you directly here.

When conservative legal provocateur Jonathan Mitchell published his 2018 law review article laying the groundwork for Texas to ban most abortions, some of the ideas he outlined were so far-fetched that they read more like thought experiments than legitimate legal theories. One was that state legislatures could give private individuals, rather than government agencies, the right to enforce abortion restrictions and other controversial statutes—a “bounty hunter”-type mechanism he claimed could make such laws all but impossible to challenge through the usual legal processes.

Another of Mitchell’s theories was even more radical: that courts don’t have the power to strike down old laws they think are unconstitutional—for example, Texas statutes first enacted in the 1850s that made it a crime to help “procure” an abortion or furnish “the means” for it. Judges can only stop those laws from being enforced, he claimed. Unless legislators actually repeal them, America’s old laws never really die; instead, they linger in a kind of limbo, automatically springing back to life if a future court issues a new, contrary ruling. They can even be enforced retroactively, he argued.

At first, Mitchell’s ideas generated little attention outside conservative circles, where some of his own ideological allies were incredulous at the notion that overturned laws might rise from the grave like zombies and be used retroactively to lay waste to the foundations of contemporary American society in a legal version of “The Walking Dead.” The University of Chicago’s Richard Epstein, Mitchell’s former teacher and one of the most eminent legal scholars on the right, told a Federalist Society panel in 2018, “Jonathan always puts the fear of God in me, because God forbid he should be right on this particular question.” Epstein added, “I think most people would say that this is an enormously dangerous-type situation.”

Undeterred, Mitchell worked with the Texas legislature to enshrine his theories in Texas Senate Bill 8, also known as the Texas Heartbeat Act. The measure not only bans abortion after about six weeks of pregnancy, but it also takes the extraordinary step of giving private citizens the right to sue anyone who helps someone obtain one.

Now, seven months after Texas’ law became the most restrictive abortion statute to take effect in the U.S. in almost 50 years, the real-world impact of Mitchell’s ideas is becoming much clearer—as well as more urgent. Even as the effort to empower vigilante citizens alarmed legal experts across the ideological spectrum, an additional—and relatively unreported—aspect of the law was gaining adherents, with implications far beyond the elimination of abortion. Most legal experts and lawmakers still haven’t understood the full scope of Mitchell’s vision for remaking American law, but as reporting from Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting shows, it’s already being adopted by legislative leaders and being tested in court.

In a series of legal proceedings, threatening letters, press releases, and social media posts, Mitchell and his allies are arguing that the 1850s statutes that made it a crime to help someone get an abortion in the state—the laws overturned by Roe v. Wade in 1973—were never actually repealed and thus are still in force. And they claim that grassroots abortion funds, which raise money to help Texas patients pay for the procedure, are breaking those old laws and should be prosecuted. Ditto for ordinary citizens who’ve donated to one of those groups.

Last month, Republican state Rep. Briscoe Cain, a lawyer and joint author of the House version of SB 8, showed just how far anti-abortion lawmakers are willing to push the idea that helping someone in the state pay for an abortion is a crime. Cain issued cease-and-desist letters to abortion funds across Texas, claiming that they are “criminal organizations” under the pre-Roe statutes and that their employees face two to five years behind bars for breaking those laws. He sent a similar letter to Citigroup, demanding that the banking giant rescind its new policy of paying for its Texas employees to travel for abortion care outside the state and warning that it will face prosecution if it continues to cover abortions in-state under its employee insurance plan.

Cain himself doesn’t have the authority to bring criminal charges, but he claims local prosecutors do. In a press release, he said he plans to push for legislation allowing them to prosecute these cases even outside their own jurisdiction. Meanwhile, saber-rattling is itself a core element of Mitchell’s legal strategy. In his law review paper, he notes that “the mere threat of future prosecution” could be enough to “induce substantial if not total compliance” with pre-Roe laws.

Supporters and opponents of the Texas Heartbeat Act demonstrate in front of the US Supreme Court in November.

Drew Angerer/Getty

Some of the most powerful conservative groups in the country have joined Mitchell’s cause, including the America First Legal Foundation, which helped defend the Texas law before the Supreme Court last fall and is now also targeting abortion funds. The new foundation was created by former White House chief of staff Mark Meadows; Stephen Miller, the architect of former President Donald Trump’s family separation immigration policy; and other members of Trump’s inner circle to “oppose the radical left’s anti-jobs, anti-freedom, anti-faith, anti-borders, anti-police, and anti-American crusade,” according to its mission statement. In a press release, Miller’s description of why America First Legal has gotten involved echoes the “tough-on-crime” language that the Trump administration made a hallmark of its often-authoritarian policies: “We will maintain the rule of law,” Miller is quoted as saying.

Mitchell’s ideas could have vast repercussions for more than reproductive rights, legal experts warn. The notion that old laws don’t go away and can be resuscitated is “awfully curious in a country where old law legalized segregation, slavery, sexual abuse and rape of wives,” said Michele Goodwin, a legal scholar at the University of California, Irvine, who focuses on issues at the intersection of gender and race. Many of these old laws, she pointed out, “subordinated people who were not white males.” If Mitchell and his allies were to succeed, she said, the result would be to resurrect a version of the country as it existed 200 years ago, when “White men controlled every branch of government in every state.”

Mitchell declined requests to be interviewed on the record for this article. But he has made it clear that he also wants to roll back decades of progress for LGBTQ rights. Over the past several years, when he wasn’t litigating abortion cases, he was filing lawsuits aimed at undermining same-sex marriage and affirming the right to discriminate against LGBTQ people in housing and the workplace. Mitchell’s culture-war campaigns converged in an amicus brief he wrote in the Mississippi abortion case that the U.S. Supreme Court will decide by this summer. His ominous warning: “Lawrence and Obergefell,” the Supreme Court cases that legalized sodomy and same-sex marriage, respectively, “are as lawless as Roe.”

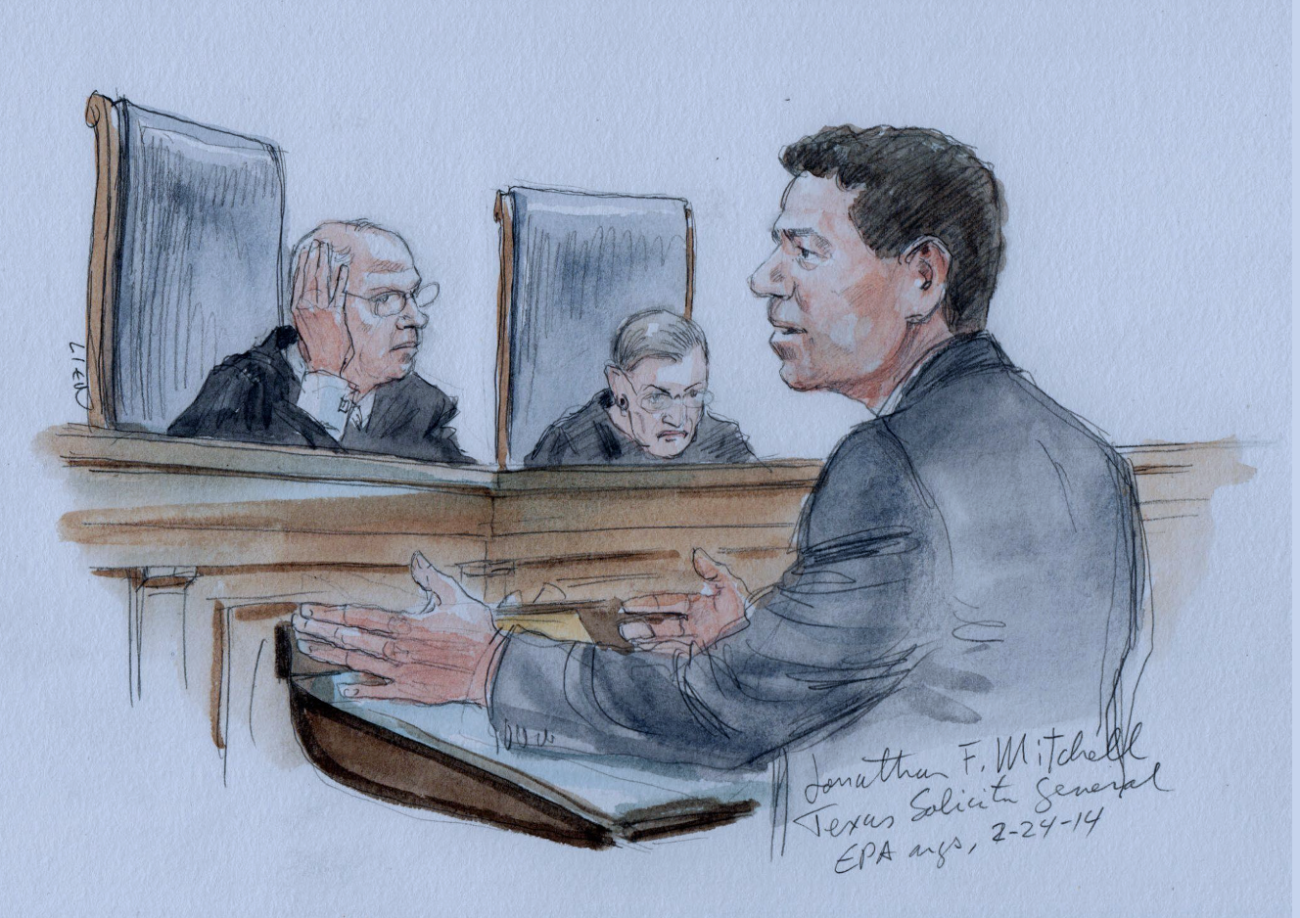

A courtroom illustration shows Jonathan Mitchell arguing in front of the Supreme Court in 2014, when he was Texas’ solicitor general.

Art Lien

Mitchell honed his ideas in some of the most elite institutions in the country. After clerking for late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, he taught at the University of Chicago and Stanford University law schools, served as the Texas solicitor general, and volunteered on the Trump transition team, reviewing future executive orders.

Just when he seemed likely to win a more permanent role under Trump—heading the Administrative Conference of the United States, a little-known federal agency that issues recommendations on how the government can work more efficiently—his nomination was scuttled because of his role in coordinating a sprawling, multistate attack on public-sector unions. The lawsuits filed in California, New York, Minnesota, and other states were funded by a shadowy litigation finance group based in Chicago that wasn’t disclosing its backers. “If he is a clandestine operative of the same powerful ultraconservative special interests out to cripple unions, he is not fit to serve in this post,” Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, D-R.I., told The New York Times.

By then, Mitchell’s law review article, which was in prepublication review and bears the wonky title “The Writ-of-Erasure Fallacy,” was already making waves. Written in 2016 and published two years later, it was based on his experiences representing the state of Texas in court, where he saw how the legislature often enacted statutes that were easily blocked—including laws that sought to ban abortion. One of Mitchell’s goals, he has said, was to prod anti-abortion lawmakers out of their “learned helplessness” by empowering them with clever strategies that would make their ideas harder to defeat in court.

That’s where the “bounty hunter” idea came in.

Geoffrey Stone, former dean at the University of Chicago law school who taught Mitchell two decades ago, nodded to the “brilliance” of the idea but condemned it as “totally obscene.” The brilliant part, Stone said, is that in order to block a law in court, you typically have to sue a government official. But if only private individuals are empowered to enforce a law, there is no government official to sue—and opponents of the law are left with their hands effectively tied. The ultimate goal, Mitchell acknowledged in his paper, was to develop laws that could circumvent judicial review. But the real-world impact, Stone and other legal scholars have suggested, is that even a blatantly unconstitutional law opposed by the vast majority of citizens and courts would still be allowed to take effect.

Mitchell then made another argument that struck at the foundations of American law. He contended that court rulings—even those issued by the U.S. Supreme Court—are far less sweeping than mainstream legal experts believe. According to his “Writ-of-Erasure Fallacy” theory, courts don’t have the power to broadly “strike down” or “erase” laws they think are unconstitutional. Even more radical, he claimed that a law could be enforced retroactively against people who violated the statute during the time period when it had been blocked.

Stone took issue with the entire premise of Mitchell’s theory during a recent Federalist Society event at the University of Chicago. The law professor—who was a Supreme Court clerk when Roe was handed down—said in an interview that his former student’s strategy “simply fails to understand the critical legal concept of precedent” that “our whole legal system is based on.”

Jennifer Ecklund, an attorney who represents the abortion funds targeted by Mitchell, found the retroactivity idea especially troubling. It “undermines the entirety of our system of constitutional justice. And that’s not hyperbole,” she said. “For this theory to take hold and become commonplace would be a complete undoing of constitutional jurisprudence in the 20th century.”

Legal historian Mary Ziegler, author of Abortion and the Law in America, pointed to how retroactivity might be used if a conservative state passed a law that criminalized sodomy and the Supreme Court upheld that new law, overturning its 2003 decision that made such sexual acts legal. “Then, in theory, that criminal sodomy law could apply not only against people who committed sodomy…after the new Supreme Court decision, it would, in theory, apply before, too,” she said.

But there was one audience that was extremely receptive to Mitchell’s legal theories: anti-abortion lawmakers and activists in Texas. Starting in 2019, Mitchell and his allies worked with more than 40 communities to pass local ordinances that created “sanctuary cities for the unborn.” Those ordinances not only banned abortion outright but also declared it to be “murder.”

Then, working with Republican state Sen. Bryan Hughes, Mitchell embedded his ideas last year into SB 8, a variation on the “heartbeat bills” that had passed in about a dozen other states, only to be blocked by the court after court for flouting Roe.

Like those other bills, the Texas version banned abortion after fetal cardiac activity could be detected in an ultrasound, around six weeks’ gestation. But as Mitchell had predicted, the law’s “bounty hunter” mechanism—giving private citizens the right to sue anyone who “aids or abets” an abortion for $10,000 per violation plus legal fees—made it extremely difficult for abortion rights groups to challenge the law in court, especially in those packed with conservative judges who shared his anti-abortion views.

But providing a way to help the Texas law withstand a court challenge was only part of Mitchell’s plan. A second goal was to explicitly revive the 1850s laws that had once made abortion a crime in the state. To that end, Mitchell and his allies inserted another provision that was almost entirely overlooked amid the firestorm over the new statute: a legislative finding that the pre-Roe laws in Texas had never been repealed.

Then they went to work.

Protesters gather for the Women’s March and Rally for Abortion Justice at the State Capitol in Austin, Texas, in October.

Sergio Flores/AFP/Getty

The Heartbeat Act isn’t the only recent Texas law that seeks to criminalize abortion, nor is it the most draconian. For example, a so-called trigger law, also enacted in Texas last year, would outlaw abortion completely and automatically if Roe is overturned; doctors who violate the ban would face up to $100,000 in fines or life in prison.

The earliest that statute could take effect is this summer, when the Supreme Court is set to rule on the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization abortion case out of Mississippi. In the interim, Mitchell and his allies, impatient to halt as many abortions as possible as soon as possible, have turned to the 1850s statutes and the writ-of-erasure language in SB 8 to try to accomplish the same thing by targeting groups that help patients pay for abortions.

References to criminalization started cropping up in court proceedings even before the heartbeat law went into effect in September. In one hearing last summer in a lawsuit involving the Austin-based Lilith abortion fund, Mitchell told a Texas judge that such grassroots groups are “criminal organizations” that are “committing crimes under state law,” even if they’re not being punished for their crimes right now.

In a major ratcheting up of their campaign this winter, Mitchell and five law firms filed petitions demanding the right to take depositions from leaders of the Texas Equal Access Fund and Lilith Fund for allegedly violating the heartbeat law. But the press releases cited the pre-Roe criminal statutes. Kamyon Conner, executive director of the Texas Equal Access Fund, said she was at a retreat with fellow reproductive justice activists when she learned about the attempts to force her to turn over information about employees and donors. “The people in the room saw my expression change and they were like, ‘What’s wrong?’ ”

For Conner, the tactic felt like an attempt to scare and shame her. Far from being intimidated, however, she and her fellow abortion fund activists decided to fight back, filing lawsuits in mid-March against America First Legal, the Thomas More Society law firm—another conservative legal group in the case—and two Texas women represented by Mitchell. The suits ask courts in Texas, Washington, DC, and Illinois—where the Thomas More firm is based—to declare the heartbeat law unconstitutional.

Thus far, donors haven’t been intimidated. Conner said the Texas Equal Access Fund has seen an uptick in what she called “rage donations,” though some check-writers are taking the precaution of blacking out their identifying information. The Lilith Fund has seen a tripling of its budget since last year—enough to begin covering the entire cost of abortions for people who need them.

Meanwhile, anti-abortion activists and lawmakers have started taking the writ-of-erasure criminalization language nationwide. In July, the National Association of Christian Lawmakers unanimously adopted a model bill that features, verbatim, the heartbeat law’s finding that the state “never repealed” its pre-Roe criminal laws. Lawmakers in at least one state with a pre-Roe statute still on the books, Arizona, have introduced legislation with this language.

Mitchell’s ideas about reviving these pre-Roe criminal statutes could become all the more relevant if Roe is overturned. In the meantime, by challenging the right of grassroots groups and private donors to help pay for abortions, he and his allies have opened a new front in the battle over access that is likely to spread well beyond Texas. Abortion funds see this as a sign of their growing significance in a landscape where access to the procedure depends on having the means to pay for it.

“I think it is very telling that the (anti-abortion activists) have caught on to us and understand us as a threat, because we are,” said Amanda Beatriz Williams, the Lilith Fund’s executive director. “We are a threat to them. We are a threat to their movement.”

Students and staff at UC Berkeley’s Human Rights Center and Investigative Reporting Program contributed additional reporting: Gisela Pérez de Acha, Brian Nguyen, Emma MacPhee, Leah Roemer, Taylor Graham, Alex Harvey, Eleonora Bianchi, Eliza Partika, Elizabeth Moss, Anabel Sosa, Rhia Mehta, Brittany Zendejas, and Sophie Hoblit. Reveal fellow Grace Oldham also contributed reporting.

Top illustration: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration; Chip Somodevilla/Getty; Gayatri Malhotra; Unsplash; Maria Oswalt; Unsplash