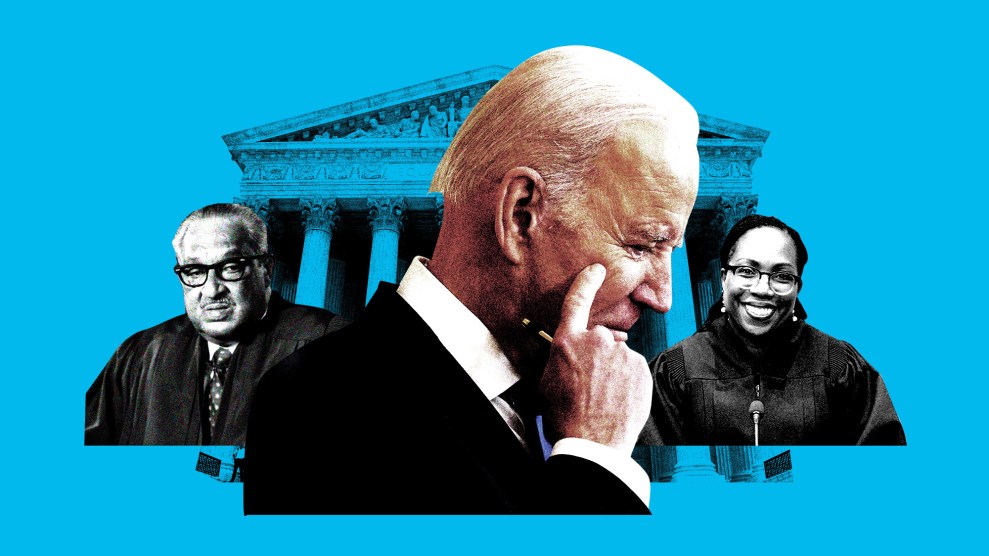

Mother Jones illustration

The last time the Supreme Court had a justice who’d worked as a criminal defense lawyer was 1991. That’s the year Thurgood Marshall, the legendary civil rights advocate, retired after 24 years on the court. Since then, the court has suffered from a dearth of justices with any sort of criminal defense backgrounds. Both Democratic and Republican presidents have stacked the court with former prosecutors, who are overrepresented on the court—people like Justice Samuel Alito, who had previously served as the US attorney for the District of New Jersey. Even Sonia Sotomayor, the court’s most liberal member, spent nearly five years working as an assistant district attorney for the legendary New York County DA Robert Morgenthau straight out of law school.

The modern court’s criminal justice jurisprudence has consistently reflected that pro-prosecutor tilt, with decisions limiting protections from illegal searches, eroding the constitutional right against self-incrimination (i.e., Miranda rights) as well as shielding cops from civil liability. President Joseph Biden has the opportunity to change some of that with his nominee to replace retiring Justice Stephen Breyer by tapping a former public defender or criminal defense attorney. Such a choice, however, won’t be easy.

The Constitution guarantees criminal defendants the right to a lawyer, and it’s a bedrock founding principle of the American legal system. One of the Founding Fathers, John Adams, represented British soldiers accused of murdering American patriots in the Boston massacre trials. Yet to hear Republicans tell it, lawyers who actually take the job of representing a criminal defendant are as morally bankrupt as the worst of their clients—unless, of course, they are defending the January 6 Capitol insurrectionists.

Hillary Clinton experienced this problem firsthand when Donald Trump attacked her during the 2016 election for her work in 1975 as a court-appointed defense counsel. Clinton at the time was running a legal aid clinic at the University of Arkansas when a judge appointed her to represent a man accused of raping a 12-year-old girl. Clinton succeeded in getting her client a plea deal for a lesser count of fondling a minor and he was sentenced to 10 months in jail. When Clinton ran for president in 2016, Facebook memes translated the case into “Hillary Clinton Freed a Child Rapist.” Trump brought the victim in the case, Kathy Shelton, to a press conference before one of the presidential debates, to trash-talk Clinton.

The Republican National Committee also ran attack ads against Clinton’s running mate, Virginia Sen. Tim Kaine, for having defended two death-row inmates as an attorney before being elected. A devout Catholic, Kaine opposes the death penalty on religious ground. Yet the RNC ads warned, “Long before Tim Kaine was in office, he consistently protected the worst kinds of people.”

Such episodes may deter a lot of good criminal defense lawyers from aspiring to the bench and even Democratic presidents from picking them. Few public defenders or defense lawyers may be interested in suffering through a confirmation process like the one Debo Adegbile endured in 2013. Obama nominated Adegbile to serve as the assistant attorney general for civil rights at the Justice Department. Adegbile had spent much of his career working at the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, the same organization founded by Thurgood Marshall. While there, Adegbile had filed a legal brief on behalf of Mumia Abu-Jamal, the journalist and former Black Panther who had been sentenced to death in 1982 for killing a police officer in Philadelphia. Abu-Jamal’s death sentence was commuted to life in prison in 2011, and he has continued to appeal his life sentence, asserting his innocence and arguing that his prosecution was hopelessly tainted by racial bias. Republicans slimed Adegbile for representing a “cop killer,” among other things, and his nomination failed after several Democrats lost their nerve and declined to vote for him.

Eighth Circuit Court Judge Jane Kelly was reportedly one of a number of women on Obama’s short list to fill the seat of the late Justice Antonin Scalia in 2016. When her name leaked, the conservative dark money group Judicial Crisis Network ran ads against her even though she hadn’t even been nominated. “As a lawyer she argued that her client, an admitted child molester, wasn’t a threat to society,” the ad’s narrator said darkly. “That client was found with more than 1,000 files of child pornography and later convicted for murdering and molesting a 5-year-old girl from Iowa. Not a threat to society? Tell your senator, Jane Kelly doesn’t belong on the Supreme Court.”

Obama didn’t nominate her.

These episodes help explain why, when Biden took office, only three of the 166 sitting federal appellate judges had spent the bulk of their previous careers as state or federal public defenders. The libertarian Cato Institute has been trying to quantify just how big the gap in experience is on the federal bench. Last year it published a study looking at the backgrounds of all the Article III federal judges. It found that President Trump, who appointed a record 226 judges in his four years in office, appointed ten times as many former prosecutors as public defenders and other defense attorneys. That’s one reason why when Biden took office, ex-prosecutors outnumbered former criminal defense lawyers by a margin of four to one.

Clark Neily, the Cato Institute’s senior vice president for legal studies and a former libertarian litigator, believes that it’s important to have people on the court who’ve advocated on the other side of the government. “Like any ecosystem it’s important to have balance among the various members that make up the group. You’re much more likely to get a good decision if you’re getting different voices,” he says, observing that eight out of the nine sitting justices have represented the government at some point in their careers. “An institution that’s that lopsided isn’t producing optimal results.”

Among the black women who’ve surfaced as frontrunners for Biden’s first Supreme Court pick, there’s only one with significant experience as a public defender. Ketanji Brown Jackson was confirmed to the DC Circuit in June to fill the seat vacated by Merrick Garland when Biden tapped him as attorney general. She spent two years working in the DC federal defender office representing indigent defendants, included a Guantanamo Bay detainee accused of terrorism. Brown Jackson also served as assistant special counsel and later the vice chair of the US Sentencing Commission, a body created by Congress to reduce sentencing disparities and increase transparency in federal criminal sentencing. And in private practice, she helped file amicus briefs in Supreme Court cases involving the indefinite detention of other Guantanamo Bay detainees. That’s more criminal defense work than any other candidate on the shortlist, making her a dream nominee for a lot of liberals who’ve been pushing Biden to nominate a former defense lawyer or public defender.

Despite her controversial clients, Brown Jackson has thus far survived three separate confirmation proceedings before Congress—two for the federal bench and once for her stint as chair of the US Sentencing Commission. Her confirmation hearing this summer for the DC Circuit was fairly demure compared with that of Adegbile. There were a few not-so-veiled racist questions, like a written follow-up from Sen. Ben Sasse (R-Neb.), who asked Brown Jackson whether she’d ever participated in a riot. (“No,” she replied tersely.) But it made few headlines for the sort of mud-slinging that Kelly and Clinton suffered because of their former clients.

If Brown Jackson is nominated for the Supreme Court, that’s likely to change. Republicans have already fouled the process in their claim that Biden is seeking an “affirmative action hire” with his plan to nominate the court’s first black woman. Throw a former public defender into the mix and things will undoubtedly get uglier.

Sasse foreshadowed the coming attacks in his written questions to Brown Jackson during last summer’s confirmation hearing, asking, “Were you ever concerned that your work as an Assistant Federal Public Defender would result in more violent criminals—including gun criminals—being put back on the streets?” He probed a similar vein by asking whether she’d ever considered giving up her representation of Khi Ali Gul, the alleged terrorist she represented as an assistant federal defender, because her work might “result in his returning to his terrorist activities.”

Those sorts of questions might incline Biden to skip the confirmation drama and nominate someone like Leondra Kruger, a justice on the California Supreme Court. Kruger has a stellar but conventional resume that mirrors that of other current justices, including Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Samuel Alito and Elena Kagan. Like them, Kruger had worked in the US Solicitor General’s office defending the US government before the Supreme Court. During law school, she interned in the Los Angeles US Attorney’s office, and after graduating, did a stint in corporate law.*

Yet Biden has shown a willingness to seek out nontraditional nominees for his appointments to the lower federal courts, including public defenders. According to the White House, about 40 percent of Biden’s lower court nominees in 2021 have had experience as public defenders. He may have the stomach to weather a confirmation process for someone who can live up to Thurgood Marshall’s legacy on the court. Besides, Republicans have already shown that they’re planning a full-court press against any black woman Biden nominates, so why not go for broke and get a former public defender on the bench too?

Correction: The original version of this article erroneously stated that Leondra Kruger had worked on an amicus brief for Philip Morris while in private practice. In fact, she worked on a brief for the petitioners who were suing the tobacco giant.