We’re driving toward Porterville, California, when Matt Black explains his attempt to escape geography. Black is a photographer, and Central Valley towns like this have long been the setting of his work, the people in them his subjects. Farmers and migrant workers. Droughts and heat waves. It’s a corner of the country he felt needed attention, the breadbasket of America. It’s his home.

Place may have been at the heart of his photography, gritty and black-and-white images rooted strongly in a social documentary tradition, but by 2014 Black had come to realize that place could be a prison, too. The iconic depictions of the Central Valley—from The Grapes of Wrath to the photos of Dorothea Lange to the more recent work focusing on the lives of Latinx migrants—seemed to lock the region into a particular set of cultural meanings. The plight of the Central Valley was seen as a California problem, detached from the larger story of poverty in the United States.

In 2014, Black decided “to escape place and all the prejudices that go along with place.” He went looking for America’s other Central Valleys—regions throughout the United States with a poverty rate higher than 20 percent. “That was a very direct way of linking places,” he says. “At first, I thought of very obvious places. I’d never been to Appalachia, the Rust Belt, the Delta. There are these headline areas, the poster children. I wanted to look beyond that. Broadening out from there, discovering all these corners of the country. Southwest Georgia. North Maine. Parts of Wyoming. They are everywhere.”

Ziebach County, South Dakota, 2016, riders. / Fresno, California, 2014, homeless camp.

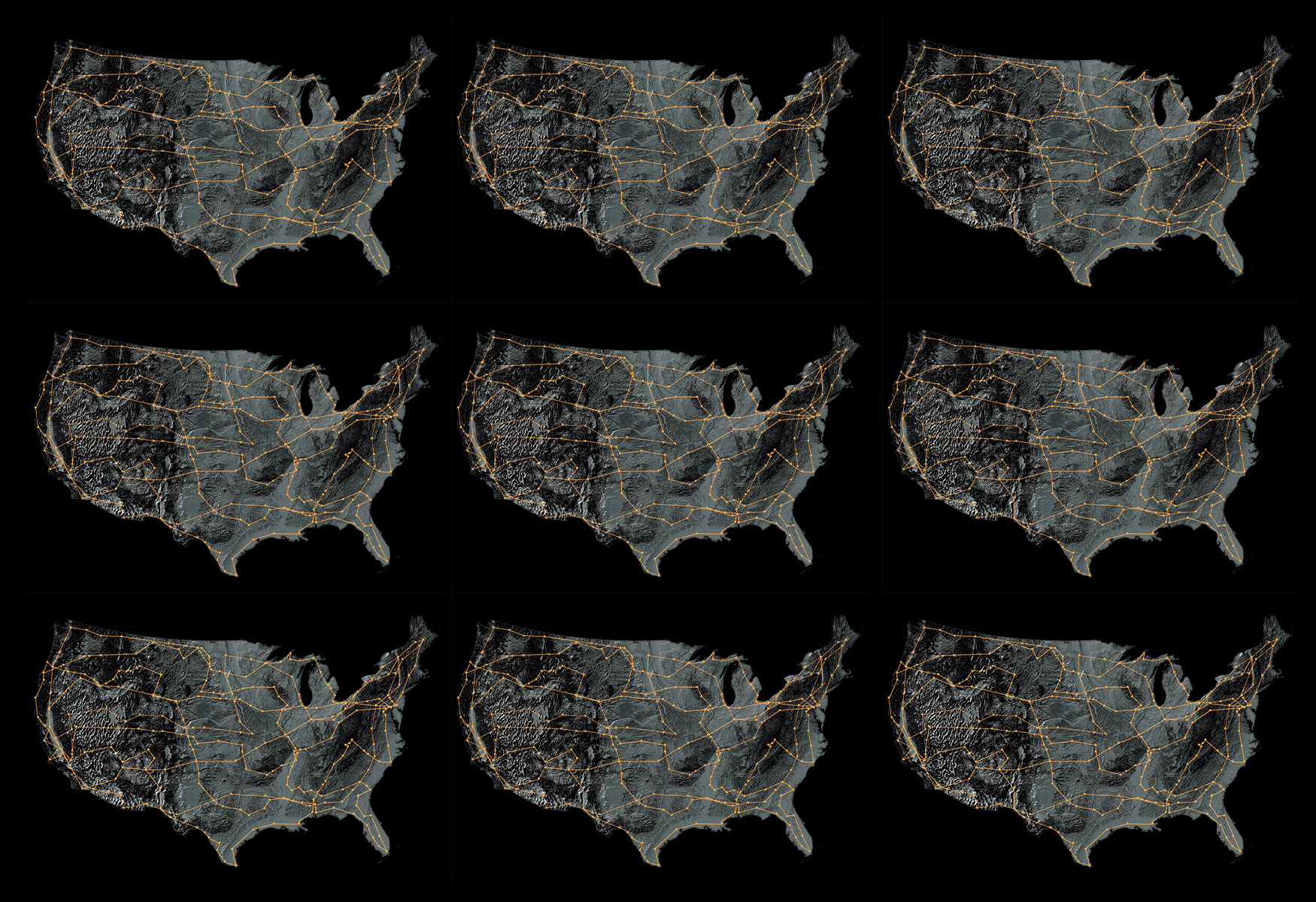

As Black plotted the destinations, his map began to get crowded. Not one location was more than two hours from another. Then he set off. He made five trips in all, traveling 100,000 miles through 46 states and Puerto Rico. The map tracing his journey shows lines ripping across the country. “Veins waiting to be opened,” in Black’s phrase.

His travels have culminated in a book, American Geography, a monumental work of documentary photography that is also, Black points out, an exercise in “critical cartography.” “Whoever draws the map decides what’s powerful, what’s important,” he tells me. He wanted to travel “an inverse map,” going instead to “all the places deemed unimportant”—the margins, the so-called Other Americas. What he found is that the whole of America today is constituted, in a very real sense, by the places supposedly on its margins. Just look at his map. The shape of America is the Other America.

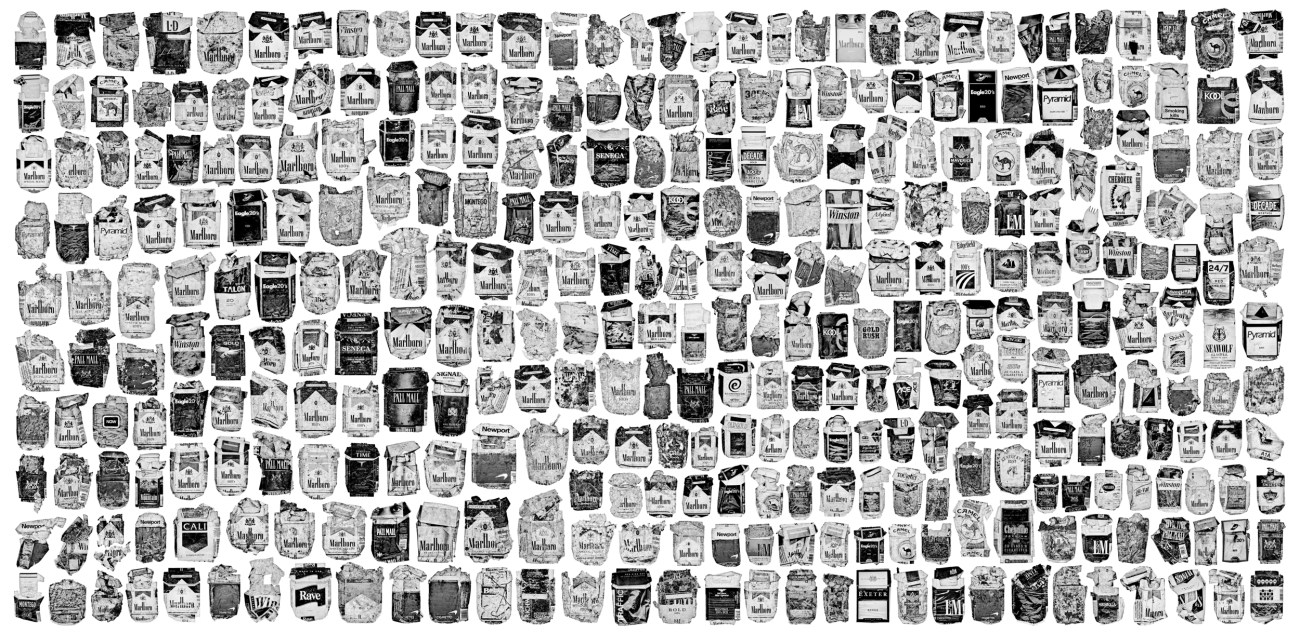

As we drive, Black mentions that, per capita, reportedly more men from Porterville died in the Vietnam War than from any other town in the United States. We pass a storefront lawyer advertising divorces on the windows the way furniture stores announce a blowout sale on recliners—big, bold colorful letters. A group of people stand outside a 12-step meeting, furiously smoking. We drive past a pregnancy crisis center and the back of a building destroyed by a fire.

“A lot of these towns we’re driving through right now,” Black says as we head back into the groves of almond and lemon trees, “there’s a profound local identity. There’s a big difference to say you’re from Lindsay than to say you’re from Porterville or you’re from Visalia. Those are the things that carry this incredible weight for people. On the most human level, it’s this question of, ‘Am I part of this America—or am I not?’”

Alturas, California 2016, cattle auction. / Lindsay, California, 2013, country road.

With his project, Black wanted to pull these local identities together, across geography, like some sort of continental Mad magazine fold-in. “You’re not encouraged to think of Appalachia and the Rio Grande Valley in the same breath,” Black says. “Put these places next to each other and you see the connections. You’re feeling the connections, too.”

The connections aren’t merely a matter of shared economic pain, Black found during his travels.

“They have a certain outlook on life. When you’re from a place like this, there’s a certain common language, a way of looking at things. A skepticism,” he says. “The more I dug into this, the more it became about social power and identity. The feeling that ‘we don’t matter.’ That’s so much more important than money. It’s not about how much cash you have. It’s about how much you and your community have been deemed to matter to the rest of us. That’s what really affects people, their self-worth, their self-esteem, their pride—where they come from.”

He goes on: “Who comes to mind first when opportunities come up? Whose houses get fixed first right after a storm? After a certain period of time, people get used to the idea that they’re not going to get redress no matter how much they try. They give up, the community gives up, they begin to look inward instead of outward.”

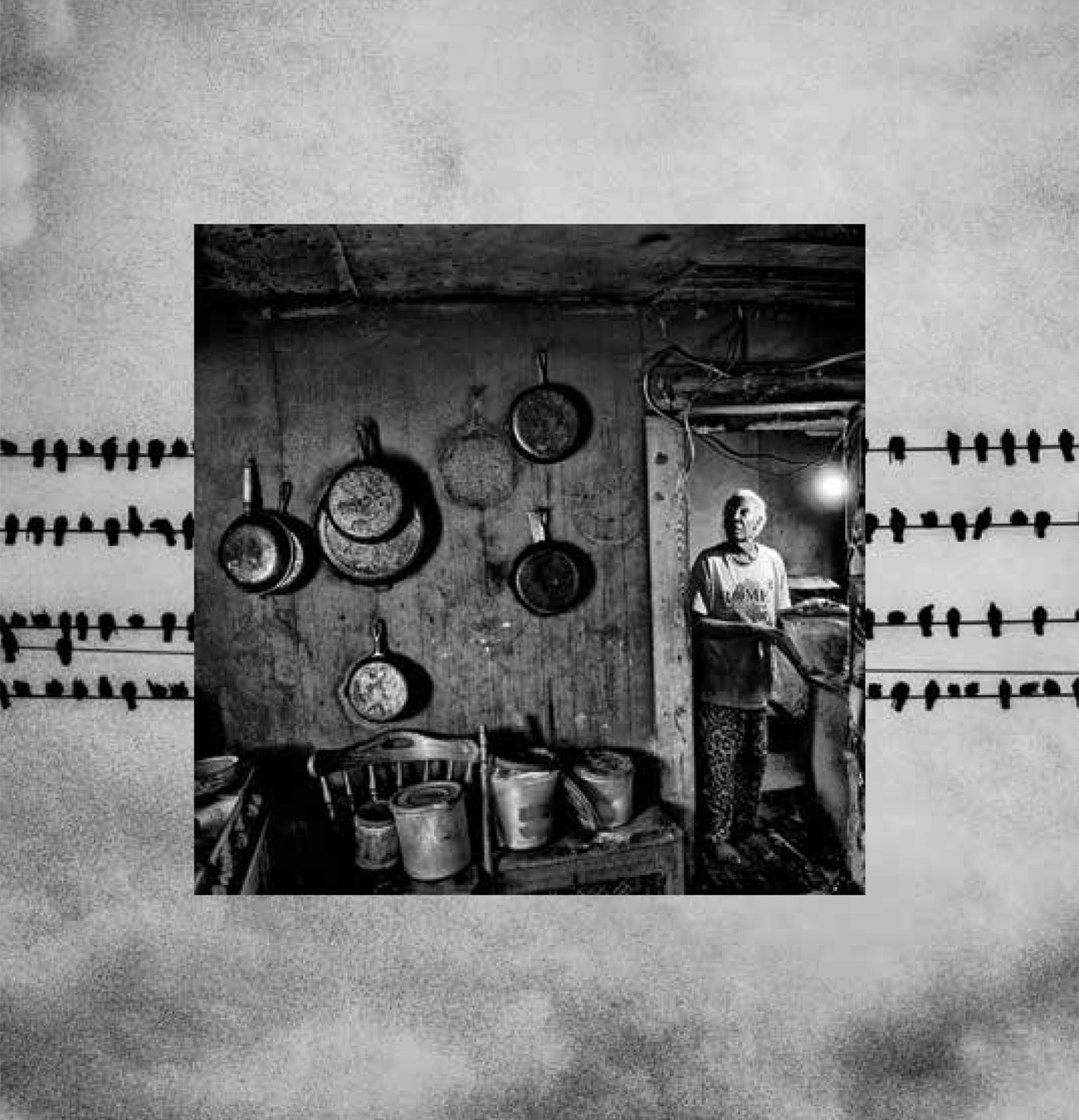

Laredo, Texas, 2018, birds. / Tulare, California, 2014, flea market vendors.

Civic failures are internalized as personal failures. American Geography is a visual tour of the culture produced and lives altered in that process. Black points his car up into the Sierra foothills, and we’re given a spectacular view of the farms and towns we’d just driven through. “It’s amazing how you internalize all that,” he says. “It matters in terms of how the country functions, whether democracy can work or not work. The American Dream. Despite all the evidence to the contrary, people still buy into it. And that’s how it works. It works because somehow it’s your fault that you’re poor. It’s your fault that your community has got poisoned water, bad air, no jobs.” Black’s voice has risen in frustration. “It’s this fundamental, hierarchical structure,” he says. “The people at the bottom of the structure have a hard time rejecting it. It’s accepted by everybody.”

Madawaska, Maine, 2019, snowstorm. / Keokuk, Iowa, 2017, Downtown.

Flint, Michigan, 2016, snowfall. / Corcoran, California, 2014, burning tires.