I’ve seen many things at the Conservative Political Action Conference over the years, including many things I wish I hadn’t. But until Ted Cruz spoke to a ballroom of activists from the main stage in Orlando in February, I had never seen an elected official interrupt his own speech to promote a podcast.

“Please go subscribe,” barked the Texas Republican, sounding more like a street performer with a SoundCloud than a second-term senator. “Verdict With Ted Cruz! Verdict With Ted Cruz! Click on ‘subscribe.’ Five stars, please!”

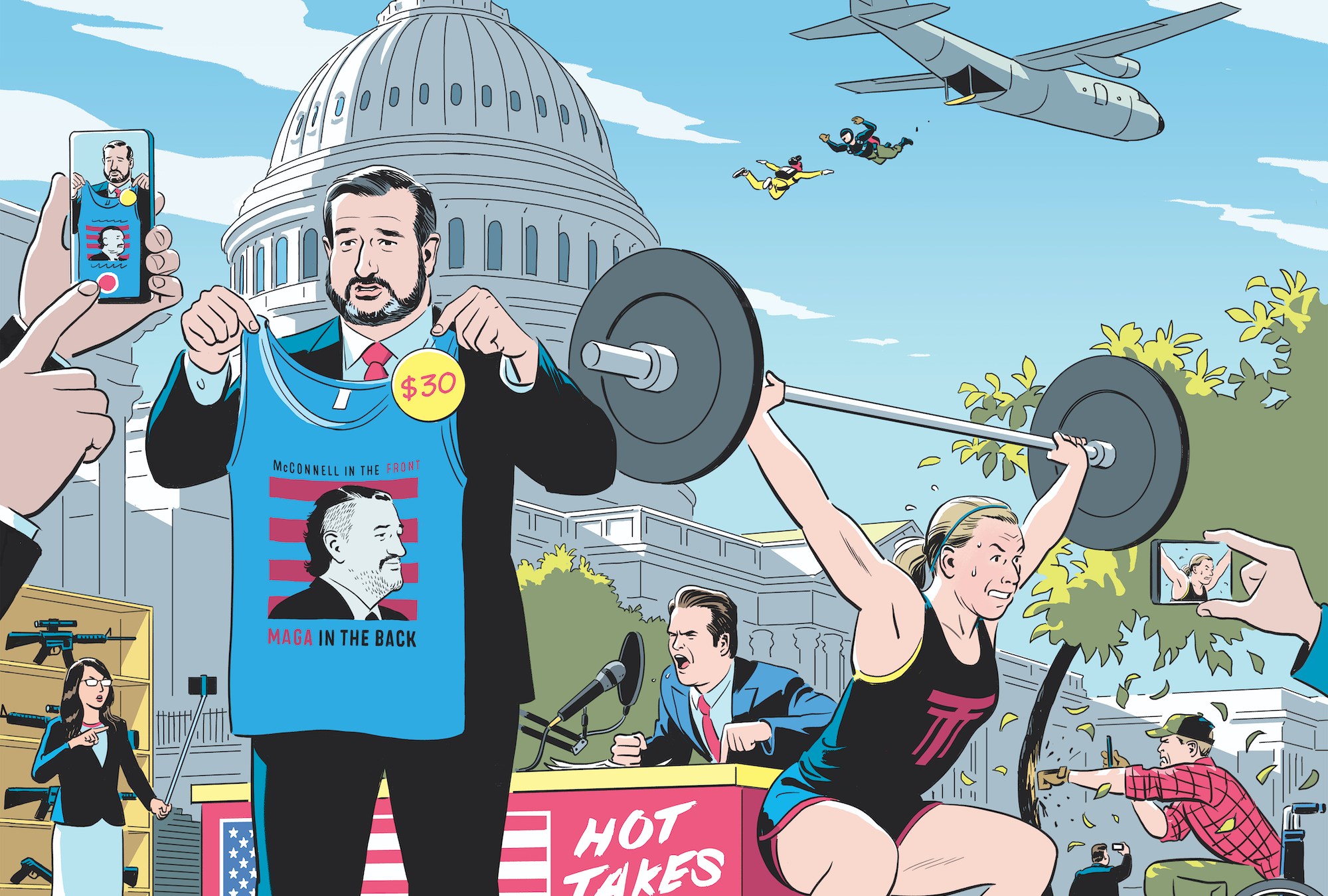

One week earlier, Cruz had left his constituents and his poodle behind to wait out his state’s deadly grid failure at the Ritz-Carlton in Cancun. It was the sort of PR disaster that would leave many politicians reeling. Cruz tried to monetize the controversy instead, printing a line of Barstool Sports–chic “spring break” tank tops with a caricature of his nascent mullet. He may never lead the Republican Party, but Cruz always knows its temperature, and in the space of a few minutes in Orlando, between jokes about his ill-advised Mexican vacation and plugs for his side project, he managed to distill this conservative moment to its essence. Increasingly, as world-historical crises unfurl all around them—often exacerbated by their own policies and actions—the GOP’s most ambitious officials view their primary responsibility less as public servants than as content creators, churning out an endless stream of takes, memes, stunts, and podcasts. So many podcasts.

For more articles read aloud: download the Audm iPhone app.

The Republican Party has long been infused with an irrepressible hustle, what the historian Rick Perlstein calls “mail-order conservatism.” Talk radio and direct mail were not only effective at peddling reactionary politics to voters; they were also perfect vehicles to sell products, such as gold and home-security systems. For decades these conjoined strains of politics, entertainment, and marketing have eroded trust in public institutions and the media and provided a template for self-aggrandizement and enrichment. There is nothing really like this on the left; Infowars and Goop sell the same pills, but Gwyneth Paltrow is not fomenting rebellion.

The way conservatism manifested itself over the airwaves has shaped what rank-and-file conservatives expect to be told and how they expect to feel about it. The late Rush Limbaugh’s listeners called themselves “dittoheads,” eager to nod along with everything. Newt Gingrich used to distribute tapes of himself talking so that candidates could emulate his language. In the 1980s, he weaponized C-SPAN’s new House cameras—where members previously addressed each other, Gingrich and his allies began speaking past them. They turned the Capitol into a studio and made politics into a product. Donald Trump easily won the Republican base because it had been primed for someone who could provide both the programming and the commercial breaks, sometimes all at once; in conservative politics, after all, you’re always being asked to buy something.

But Trump’s presidency blew past the old frontiers: The performance of politics became the purpose of it, and the grind of governance became secondary to the responsibilities of posting. It was as if, after years of awkward but largely profitable power-sharing between conservative politicians and conservative media, the Republican Party at last stumbled upon the ultimate efficiency: What if both roles could be played by the same person? Trump once dreamed of spinning a losing presidential bid into his own media entity. During the pandemic, in lieu of crisis management, he turned briefings into a variety show, assembling a rotating cast of characters, and plugging an array of sponsors—MyPillow, Carnival, Pernod Ricard. You would not necessarily get good medical advice, but you would learn that Hanes is a “great consumer cotton products company” that’s being recognized more and more.

There was no issue grave enough to take seriously and no controversy too petty to weigh in on. Anything could be resolved via tweet, precisely because nothing really can; the ephemerality was the point. And a rising generation of politicians learned an important lesson about what conservative voters wanted. If Limbaugh taught them all how to talk, Trump taught them how to govern. His enduring gift was a caucus of content creators.

Just consider the Republican congressional class of 2021—the new arrivals to Washington who modeled themselves most directly after Trump. They seem almost blissfully detached from the work of Congress. There is 25-year-old Madison Cawthorn of North Carolina, who was elected on the strength of a largely invented personal story amplified with loads of influencer-style Instagram posts. He recently posted a 19-second video of himself punching the bark off a tree. Cawthorn boasted to his colleagues that he had built his staff “around comms rather than legislation.” He was in Washington, in other words, mostly just to post.

When Marjorie Taylor Greene, the QAnon representative from Georgia, was stripped of her committee assignments in February by colleagues upset that she had harassed fellow members of Congress and blamed forest fires on the Rothschilds, she greeted the news with relief. “If I was on a committee, I would be wasting my time,” she said. Now she was more free to share videos of her CrossFit workouts with the hashtag #FireFauci. Not that showing up for committee hearings necessarily means you’re there to work. Colorado’s Lauren Boebert, who like Cawthorn and Greene spent her first weeks on the job scaring the shit out of her co-workers, recently hijacked a virtual committee hearing by posing like John Wick in front of a shrine of firearms in her living room. (“Who says this is storage?” she responded to critics. “These are ready for use.”)

Cawthorn, Greene, and Boebert were all members of the National Republican Campaign Committee’s “Young Guns” program, which takes its name from an earlier trio of House Republicans—one of whom, Paul Ryan, went on to become a vice presidential nominee and speaker of the House and unite the party behind a vision of budget austerity. There is surely some sort of ideology at work here, too, but it’s more Jake Paul than Paul Ryan; they are treating the Capitol like their own hype house, using the stature of their office for clout.

These younger, gunnier guns are taking cues from their elders. Texas Rep. Dan Crenshaw, a content farm of a congressman who has filmed not one but two Avengers-style videos in which the ex–Navy SEAL parachutes out of airplanes to fight Democrats, also hosts a podcast. So does Devin Nunes. Florida Rep. Matt Gaetz has a podcast called Hot Takes. Before he became publicly embroiled in a federal sex-trafficking investigation (“If you aren’t making news, you aren’t governing,” Gaetz once said), he was considering retiring to take a job at the conservative cable channel Newsmax. In February, more than a dozen House Republicans—including Gaetz and Nunes—skipped work to speak at CPAC with Cruz. They took advantage of a covid-era policy that let members vote by proxy in medical emergencies; to them, promoting their brands is the job.

After watching Cruz’s speech I took his advice and checked out Verdict, which he co-hosts with Michael Knowles, who rose to prominence after publishing an entirely blank book called Reasons to Vote for Democrats. Cruz recorded the first episode at 2:40 a.m. after the opening day of Trump’s Ukraine impeachment trial—hence the name of the show—and returned to the studio every night of the proceedings. Within days of its debut, Verdict had passed Joe Rogan on the iTunes charts. At CPAC, Cruz announced it had been downloaded 25 million times. It is almost certainly the most popular thing he has ever done.

From the start, there were gestures that this was all “for work”; while Cruz plugs his book with regularity, he does not hawk brain pills or sell ads. In the premiere episode, Cruz solicited listener questions he could ask during the impeachment. When Knowles asked him why he was doing the show, Cruz replied with two words: “Substance. Matters.”

This is true in a technical way: Cruz talks on his show about many of the things he and his Republican colleagues talk about in the Capitol. But that Washington conversation is increasingly just an extension of what they talk about on their podcasts. The biggest crises in America right now, according to Cruz, CPAC, and Trump, are the interlocking threats of Big Tech and “cancel culture.” Hearings with tech executives have become a must-watch for conservatives. Cruz advertised his hearing-room clash with Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey last summer with a Christopher Nolan–ish movie trailer and a poster reminiscent of welterweight boxing—“The Free Speech Champion vs. the Czar of Censorship.” There are substantive things to say about corporate power, but this brand of conservative opportunism zips past what’s real to fixate on what isn’t. Twitter moderators, or someone being “canceled,” is not something Congress is really positioned to do much about. They are just creating content about content creation; this is the uroboros of mail-order conservatism.

Big Tech and “cancel culture” have emerged as key villains for the new right, not just because of how neatly they fit into long-standing tropes about “cosmopolitan elites,” but because so much of modern conservatism lives online. Offline, there are issues that warrant serious attention from one of the nation’s two governing parties—cities without water, cities soon to be underwater, whole states without power, and a world still suffering from a deadly virus. But with a nudge from Trump, the right has become ever more dissociated from reality, channeling its energy into an endless series of fights over “deplatforming” and who’s triggering whom. During the Obama years, a Breitbart provocateur interrupted a White House press conference to complain about losing his Twitter verification badge. Then, it was a sideshow; now, it’s the whole point. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, a likely presidential candidate, recently signed a law prohibiting social media companies from banning public officials.

The rise of politics as content creation is hardly the sole domain of the right. After his 2016 presidential campaign ended, Bernie Sanders kept his media imprint running. He organized town halls on Facebook Live and recorded a regular podcast. Sanders, who has made no secret of his distaste for corporate-owned media, hoped to build out his own information stream for his supporters. So did Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the New York representative whose prolific posting has gotten her in trouble with other members of her caucus. (Her arrival in Washington precipitated a closed-door meeting in which a colleague pleaded, “Everyone stop tweeting!”)

The content creators of both the left and the right pose some of the same big-picture challenges—the rise of politicians as independent news sources, of politics as stan culture, and the acceleration of the permanent campaign. A Pew analysis found that the outgoing 116th Congress was one of the least productive of the last half-century, but the most prolific ever when it came to posting. Members sent 50 percent more tweets than they did two terms ago; they were still talking—just not to each other. The more politicians function as affinity brands peddling a product to be consumed, the more “politics,” the entertainment vehicle, becomes dissociated from politics, the distributor of power. Barack and Michelle Obama run a media company now and each hosts podcasts, too; the ease with which political figures can rebrand themselves as entertainers speaks to the two spheres’ increasing coziness. This is not what “seizing the means of production” was supposed to mean.

But the way this dynamic is unfolding on the left and the right is asymmetrical. Though you would not necessarily know it from listening to Gaetz, Obama is not in office. Sanders and Ocasio-Cortez are not angling for TV gigs; nor are they reducing the world of lawmaking to the kind of retrograde distractions that get you booked on Tucker. They use their enormous social media platforms for civics lessons, offering behind-the-scenes glimpses of the legislative process and the work of movement building, in an effort to get more people invested in both. You can buy the “Tax the Rich” sweatshirt Ocasio-Cortez wears when she holds court on policy and procedure on Instagram Live, but it is not the only thing she is selling. She and Sanders are trying to make the online world more engaged with the real world, rather than the other way around, to advance an ambitious governing program. It is a theory of change, of which clout and performance are merely a means, not the endpoint, of politics. That is the opposite of the reductive nihilism of Cawthorn or Boebert, or the eternal stagecraft of Cruz.

In the first few months of the Biden administration, the world of Twitter and real life have become increasingly estranged. In a paradoxical way, the transformation of a major political party into a meme factory has even eased some of Washington’s dysfunction. While Republicans were pitching their podcasts and talking about Dr. Seuss and his imaginary canceling—Cruz began selling copies of Green Eggs and Ham, signed by himself—Democrats pushed through a $1.9 trillion covid relief and stimulus package with little dissent.

In March, Trump, banned from Facebook and Twitter, announced that he was considering launching his own social media network. “I’m doing things having to do with putting our own platform out there,” he promised. “You’ll be hearing about [it] soon.” The website he unveiled didn’t amount to much, but that’s what made it so perfectly Trump—there’s not supposed to be a there there. Meanwhile, younger Republicans aiming to take his place continued their auditions. In April, Marco Rubio called on the government to treat companies that pollute “our culture” just as harshly as it treats companies that pollute our water—sort of like an Environmental Protection Agency for tweets. Cruz, himself accused of poisoning the discourse by John Boehner, polled his hive on whether he should shoot the former speaker of the House’s new book with a machine gun. But none of the Republicans vying for Trump’s role have embraced the new posting reality as fluidly as DeSantis. In May, not long after guaranteeing Florida politicians the right to shitpost, DeSantis scored his biggest coup yet: passage of a bill to roll back voting access in the state, fueled by Trump’s lies about the 2020 election. When it came time to sign it, local reporters were stopped at the door—only a crew from Fox and Friends got in. DeSantis had turned an attack on fundamental rights into a live television event. Supporters of the ex-president stood behind him, cheering on cue, as the governor bantered with the hosts via satellite. Then he picked up a blue Sharpie, scrawled his name, and held up the embossed legislation for the cameras.

Trump may be gone, but the show never ends.