Brazil's President Jair Bolsonaro during a protest in favor of the government and against the lockdownAndre Borges/NurPhoto/Getty

The day after Twitter permanently suspended Donald Trump’s official account following the US Capitol insurrection on January 6, Brazil’s president, Jair Bolsonaro, invited his 18 million Instagram followers to join the conservative social media site Parler. Bolsonaro, as well as members of his Cabinet and family who echoed Trump’s baseless claims of fraud in the 2020 presidential elections, had been active in the self-described uncensored platform favored by the far right since July and lauded its promise of freedom of expression. Several days after the insurrection, Apple and Google moved to block the social media app from online stores, and Amazon suspended it from its hosting services, citing the company’s lack of moderation of violent content. In response, one of the Brazilian president’s sons said Parler was a victim of the “big tech cartel.” Other Bolsonaro supporters called it “a plot to silence conservatives around the world.”

Around that time, Marco Aurelio Ruediger, a political sociologist and director of the Getulio Vargas Foundation’s Department of Public Policy Analysis, a nonpartisan social research center, became interested in investigating the response of the Brazilian far right to anti-democratic rhetoric in the context of the US elections and the storming of the Capitol. With a weakened Bolsonaro preparing for what is shaping up to be a dramatic and highly contentious presidential dispute in 2022, understanding the influence of Parler and outside actors has gained special urgency. This is where, Ruediger says, “basically everyone on the right who operates in the political debate in a significant way in Brazil is.” So in February Ruediger and a team of four researchers took a deep dive into an open dataset of Parler posts.

The original data made publicly available by researchers from US and European universities included more than 180 million posts and profile metadata for about 13 million users. Ruediger’s team decided to focus on worldwide posts limited to the time period between November 3 and January 7, 2021, which amounted to 93.4 million publications. What they found was a relatively small but close-knit and highly articulated group of profiles linked to the conservative movement in Brazil, which turned out to be the most active country on the platform after the United States. The American far right, researchers concluded, had become the “guiding light” for the Brazilian network, which repeated similar arguments that had been used in the United States to call into question the fairness of Brazil’s electoral process and institutions.

“The sharing of conspiratorial and denialist ideals should serve as a warning so that actions to discredit democracy or attack institutions are not mimicked on a global scale,” states the study shared in advance with Mother Jones and first reported by Brazil’s newspaper of record, Folha de S. Paulo. It further warns against “the ideological interference of right-wing extremist groups or countries with authoritarian regimes” in next year’s Brazilian presidential elections because “Brazil cannot become a geopolitical game of anti-democratic radicals.”

Ruediger agrees. In light of what happened in the United States, he wonders: How will it play out here? “It’s very worrisome because many of these ideological fantasies become politics that are put into practice in Brazil,” he says. “The speech is not only reproduced, it turns into the official speech of the government.”

The group of active profiles in Brazil—which included the president, lawmakers, other politicians, and influencers aligned with or supportive of the government—engaged primarily with content related to allegations of voter fraud. More than half the 8,138 monitored accounts with links to Brazil had at least one interaction with posts in either Portuguese or English related to the theme of distrust in the electoral system, sometimes bringing the discussion back to context specific to Brazil. A popular post among users had to do with calls for the implementation of printed ballots, an agenda that is dear to Bolsonaro. He has long been casting doubt on the country’s highly efficient and safe electronic voting machines, which he claims robbed him of a victory in the first round in 2018. “If we don’t have the ballot printed in 2022, a way to audit the votes, we’re going to have bigger problems than the United States,” Bolsonaro said in early January.

During the period analyzed in the study, some US accounts were notable for having prompted thousands of reactions from profiles linked to Brazil. Among them was Trump’s official campaign account, TeamTrump, and former White House chief strategist Steve Bannon’s podcast, WarRoomPandemic, in which he shares conspiracy theories. The day before extremists invaded the Capitol, Bannon told listeners: “All hell will break loose tomorrow. It will be quite extraordinarily different. All I can say is strap in. Tomorrow is game day.” The Brazilian far right on Parler also responded to publications by QAnon-supporter Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-Georgia) at least 700 times and interacted with posts from accounts with millions of followers such as the conservative commentator Dan Bongino and Fox News host Mark Levin. They were also receptive to content published by the Trump loyalist, conspiracy theorist, and Atlanta lawyer L. Lin Wood, (who recently made QAnon gestures before a crowd). Also gaining attention were the British far-right activist Tommy Robinson and a virologist who spread misleading claims that China created the coronavirus in a Wuhan lab.

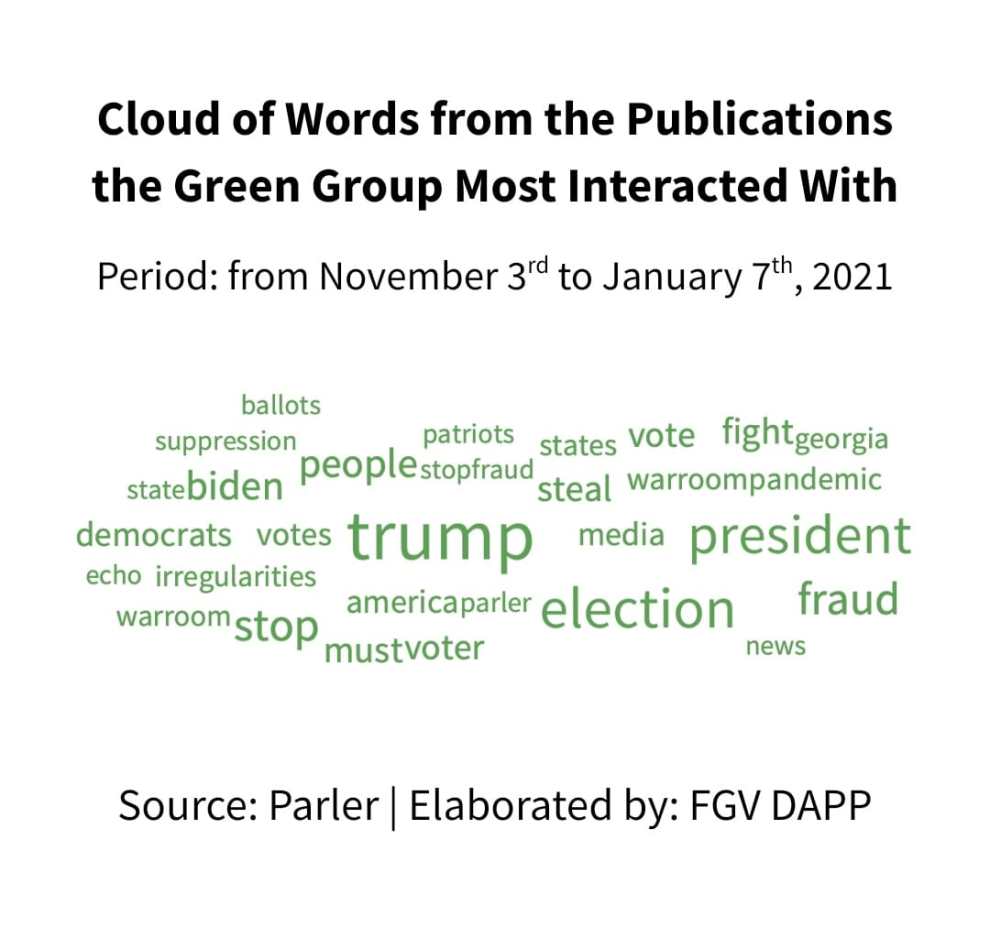

The researchers also monitored the content of interactions within the group of Brazil’s profiles on Parler and found “a strong presence of terms related to the American context.” The image below shows a word cloud representation of those findings with references to states where Republicans challenged election results such as Arizona, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Georgia, on top of catchphrases like “Drain the swamp” and “Vote red to save America” and Trump’s slogan MAGA.

Word cloud representation of interactions among Parler profiles linked to Brazil.

Parler/FGV DAPP

“The reaction of American institutions against the demonstrators [who stormed the Capitol] and the inauguration of Joe Biden are not guarantees of the neutralization of anti-democratic speeches,” researchers note in the study, “especially when observing the reception of these narratives by leaders and activists in other countries.”

After finding a new hosting platform, Parler made a comeback in February, heightening concerns about the potential for further radicalization of far-right sympathizers and key political players ahead of the 2022 presidential elections in Brazil. Bolsonaro is facing a congressional investigation into his handling of the pandemic and calls for impeachment from opposition leaders denouncing his “coup-mongering” attempt to co-opt the military. The armed forces have so far resisted pressure to align with the government’s politics, leaving a cornered Bolsonaro with few options other than to galvanize his grassroots supporters—not unlike Trump. The difference, Ruediger says, is that Brazil has less solid and resilient institutions, and the armed militias, largely composed of acting and former police officers, firefighters, prison guards, and members of the military, already operate as a parallel state in many cities. “What can happen next year?” he asks. “Anything.”