Even while the votes were still rolling in, it had become axiomatic among the green-room set that Democrats had hurt themselves by focusing too much on “cultural issues.” Surely you’ve heard the argument before. It arrives every four years on the button, glib and overwrought and covered in pancake makeup, like the Olympic gymnastics all-around.

“In their minds,” Andrew Yang said on CNN two days after the election, referring to the working-class people he’d met on the trail during his bid for the Democratic nomination, “the Democratic Party unfortunately has taken on this role of the coastal, urban elites who are more concerned about policing various cultural issues than improving their way of life that has been declining for years.”

The returns needed to be explained. Democrats had failed to win a thumping mandate, and their failure once again was thought to be most acute among the white working class that used to make up their base. Everywhere you turned in the aftermath of the election, there was someone arguing the hard line on cultural issues as a way of accounting for the outcome. Al Franken on MSNBC. Abigail Spanberger. Bill Maher. Bill Freaking Simmons. “I had a friend ask me yesterday why I thought white people who made less than $50,000 a year in a million years would vote for Trump, given what happened the last four years,” said Simmons, a podcaster. “It was about, you know, a reaction to cancel culture and the woke left and celebrities and kind of being told what to do.”

For more articles read aloud: download the Audm iPhone app.

The point was made in different ways, by different commentators of at least outwardly different political persuasions, with different code words and different bogeys—feminists, socialists, police abolitionists, transgender people, social-justice warriors, wokeness, identity politics in general. However they might have varied in their particulars, these arguments all circled the same thesis: The members of the working class—by which is always meant the white working class and very often, incoherently but significantly, the white middle class, too—have fled the Democratic Party because of its abandonment of the firm materiality of class politics for the soft superfluities of culture and identity.

By my calculations, we are now in the fifth decade of people making some version of this claim. It is the great tonic chord of American political punditry. That the argument is constructed on a set of patronizing assumptions about the limited moral capacities of white working-class voters has never much damaged its popularity. Nor do the culture-war contras care that the analysis doesn’t make sense even on its own impoverished terms, as the great Ellen Willis pointed out years ago in her essay about the genre’s paradigmatic text, Thomas Frank’s What’s the Matter With Kansas?

The critics’ premise has two parts, the one at odds with the other. The first is that these cultural issues are so powerful as to dislodge certain workers from their “natural” affinities and antagonisms, as crudely reckoned by their class position. One glimpse of the specter of wokeness and they go running into the arms of the party of the bosses and plutocrats who hate them. The second is that these cultural issues are so flimsy and evanescent as to vanish at the mention of “meat-and-potatoes issues,” as Claire McCaskill put it on MSNBC the day after the election.

Which is it? Are cultural issues a set of powerful currents that buffet people around the political spectrum? Or are they a collection of irrelevancies and distractions with no real substance or meaning, lightly worn and easily dismissed? And why is it that the only option for the left here is to concede? Why is the culture war, in this particular vision of cultural conflict, only ever perceived to be won by conservatives, even in the face of all sorts of evidence to the contrary?

These questions never seem to get answered. Maybe that’s because this sort of analysis isn’t an explanatory effort anyway. It is a continuation of an ideological one, that vast lowering of horizons by which the age of austerity contrives to extend itself, winning people anew to the conviction that there are no moves left for them but to fight for a share of a dwindling pile of stuff. It is the politics of stalemate.

The clearest articulation of the culture-contra argument belonged to McCaskill, the former Missouri senator and MSNBC regular. Why McCaskill is being asked to comment on elections in the first place is another matter entirely. She spent her two terms in the Senate clinging with both hands to the right flank of the Democratic Party, and then, in 2018, a blue wave election year, she wound up getting herrenvolked out of the job by Josh Hawley anyway. Bringing her on to talk about what Democrats need to do to win in this environment is a bit like asking the Washington Generals for advice on how to beat the Lakers. And yet here she was just after the election, mewling as she has throughout her career that Democrats have “left some voters behind” with their emphasis on “guns or issues surrounding the right to abortion in this country or things like gay marriage and the rights for transsexuals.”

McCaskill eventually apologized for referring to transgender people as “transsexuals,” not fully grasping the nature of her offense. Like a lot of people who dismiss identity politics, she was positing the humanity and bodily autonomy of certain Americans as “issues,” something subject to negotiation, perhaps to be horsetraded away for a few points in an election-year Gallup poll. That she used the musty old diagnostic nomenclature, with its air of last century’s sex panics, only reinforced the sense that she saw these humans principally as the sum of other people’s anxieties.

Here’s her full quote:

Around cultural issues, the Republican Party, I think, very adroitly adopted cultural issues as part of their main theme—whether you’re talking guns or issues surrounding the right to abortion in this country or things like gay marriage and the right for transsexuals and other people who we as a party have tried to look after and make sure that they’re treated fairly.

As we circle those issues, we’ve left some voters behind, and Republicans dove in with a vengeance and grabbed those voters. You’ve seen this shift. You see it in the South. I see it in the rural areas of my state. So we’ve gotta get back to the meat-and-potatoes issues. We’ve gotta get back to the issues where we are taking care of their families, and we’ve gotta stop acting like we’re smarter than everybody else. Because we’re not.

McCaskill seems to have her cultural history backward. In the realm of discourse, at least, where these voter-alienating offenses are allegedly being committed, the left is on a big winning streak. The fact she felt compelled to apologize is a sign of this. On some level all the culture-contra pundits know it, which is why their political analysis seems so forked. They complain about the hegemony of identity politics and in the next breath urge, as a matter of cold-blooded realpolitik, that the Democratic Party defy the hegemon. There’s so much potent, culture-shifting wokeness afoot, they complain. Democrats have no choice but to…reject it?

This isn’t a contradiction so much as a statement that it doesn’t count as winning if the winners don’t really count. Take a look at how McCaskill balances her equation. There are the vulnerable, people who exist as political creatures at the sufferance of the Democratic Party, and there are the “voters.” Her invocation of the “voters” here, with their families and their kitchen-table issues, is doing some slyly invidious rhetorical work, akin to the sneaky whitening and gendering that happens with “taxpayers” and “workers.” These are special categories, reserved for those Americans who get to move through the discourse without ever having to show their papers—Americans who count.

Presumably white, implacably conservative in their cultural attitudes, these voters enjoy the great privilege of having their political choices naturalized, explained away if necessary as some sort of forgivable immune response. When they vote for reactionaries, it’s because of an allergy to left-wing overreach or because of anxieties brought on by the economy or because of a bout of false consciousness inflicted upon them by a conspiracy of elites. We’re told they’re discombobulated by cultural dynamics they can’t comprehend, that they’re hoodwinked into voting for Republicans against their own “real interests,” as construed by other people. These voters are the eternal innocents of the electorate. They don’t have any politics of their own. They have meat and potatoes.

The innocence is central to the story being told, one in which a sort of vulgar Marxism prevails. Pundits and political figures across the political spectrum, from reactionary liberals like Claire McCaskill to right-handed class warriors like Michael Lind to lefty polemicists like Thomas Frank, come together in a shared vision of white workers as lumps of inchoate class feeling who, but for the corporate propaganda of the right or all that identity crap on the left, would eagerly transmute their economic position into legible populist voting patterns.

The narrative leaves no room for the possibility that white working-class voters, exploited though they may be, might also derive benefits, material and otherwise, from the subordination of other people. That they might actually be voting their interests when they vote for the party of the racial and gender caste system. That class alone can’t account for the attractions of authoritarian populism, even a program as shambling and mealy-mouthed as Donald Trump’s. Four years later, our political culture still can’t see the appeal of someone like Trump because it refuses to see how people’s material concerns, about their jobs and their wage and their health, are bound up with their values, their identities—their culture.

How could it be any other way? Just as “capitalist society was founded upon forms of exploitation which are simultaneously economic, moral and cultural”—that’s E.P. Thompson, drawing on the 19th century socialist and textile designer William Morris—so are the politics of living in such a society being worked out along multiple axes at once, at different tempos. This is something people understand on an intuitive level, then seem to forget somewhere between the street and the CNN studio. Maybe you have a shitty job and a shitty wage, but in the roiling mix out of which you make your politics there are also all the rationalizations for the shittiness, the privileges you earn for accepting them, the larger sense that your freedoms, however meager, gain strength in contrast to the unfreedoms of others, and so on.

In such a world, the material cannot be so easily cleaved from the cultural. Is it material or cultural for gay Americans to demand civil equality? Is it material or cultural for women not to want to be subordinated to the reproductive function of their bodies? Is it material or cultural for transgender people to wish for bodily autonomy? What about the fact that they are, by one recent accounting, much more likely to be unemployed than the general population, much more likely to have salaries below $10,000, much more likely to make less than $30,000 even when they have college degrees? Is that material? Is that cultural? How much less meat, how many fewer potatoes could Aimee Stephens afford after she was fired from a funeral home for being transgender?

And what about the cops? Looking over the election returns, the anti-wokes giddily discern a backlash inspired by the sloganeers of the police abolition movement and the Black Lives Matter movement more broadly, though the evidence of a backlash is thin and uncertain and in any case could never be disambiguated from the many other causes of a law-and-order turn in the populace. (“Backlash” is another of our exonerating metaphors. It calls to mind the interplay between misfit pieces of a machine. But here we have certain classes of Americans defending their prerogative, as enshrined in the formal and informal terms of the country’s founding, to dominate other classes. This isn’t one part of the machine recoiling from another. This is the machine.)

The pundits’ triumphalism is confusing if we take at face value their entreaty to focus on economic claims. What is “defund the police” if not a straightforward redistributive demand? But of course some people’s economic claims count for more than others’, which is why you find “defund the police” among the excesses enumerated by Bill Maher in an excruciatingly stupid riff about Democrats having become the party of “every hypersensitive social-justice warrior woke bullshit story in the news.”

The issue of policing confounds all the culture-contra premises. That’s because it is a vivid and violent demonstration of the unity between the material and the cultural, something of which is suggested in the very phrase “law and order.”

Some relevant history, via Jack Norton and David Stein:

For 1960s policymakers—operating during the Cold War—crime, civil rights, communism, and the looming expansion of the welfare state were braided together. In May 1968, when Arkansas Senator John McClellan argued on the Senate floor for the 1968 Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act, a watershed piece of federal crime policy, he invoked popular fear of the civil rights movement and the Poor People’s Campaign. McClellan quoted the Southern Christian Leadership’s Conference’s James Bevel’s demands for economic justice—guaranteed jobs or income—and argued that the new crime bill was needed to stymie this movement. “Senators should understand they are not requests, they are demands…Force, intimidation, and coercion, if it becomes the process by which we govern ourselves in this country, will destroy our liberty and force an end to the sovereignty of government,” McClellan warned. To arrest this movement, McClellan sought to increase the federal, state, and local capacity to criminalize the multiracial working-class.

Where the cultural leaves off and the material begins is impossible to make out. To even try to tease them apart is to miss the point. What was it that Andrew Yang said again? Something about “policing” cultural issues? The metaphor was truer than the analysis around it.

What Yang and McCaskill and all the rest are describing and then enacting anew is a stalemate, the condition toward which all our politics have been impelled in this long era of scarcity. The tendency to carve out neat divisions between material and cultural interests is at least as old as Karl Marx’s base and superstructure—Friedrich Engels had to ding the culture contras of his day for being too frisky with the metaphor—but the modern move of positing all politics as a zero-sum tradeoff between one or the other dates back more than half a century, to the rollback of the welfare state and the erosion of its coalition. These dynamics begat a cottage industry of people puzzling over the contradictions of the new order—unionists voting for the union-busters; Americans in the cradle of prairie radicalism turning the wrong sort of red; Floridians approving a $15 minimum wage in the same cycle that they go for Trump—while still operating under the assumptions of the old one.

Foremost among these analysts was Stanley Greenberg. In 1985, at the request of the United Auto Workers, Greenberg began conducting focus groups in Macomb County, Michigan, once a stronghold of the Democratic Party, to figure out why so many of its members had decided to throw in with Ronald Reagan. “The very invitation for him to study Macomb County grew out of a sense that Democrats needed to shift away from racial justice and feminist issues,” David Roediger writes in his excellent The Sinking Middle Class: A Political History.

Greenberg is a funny figure, a Marxist academic and an astute analyst of revolutionary South Africa who later fetched up in political polling and became a sort of class warrior of the revanchist center. It was Greenberg who helped Michael Dukakis’ 1988 presidential campaign with the “race issue” after George H.W. Bush decided to turn Willie Horton into Stagger Lee. It was Greenberg who devised the political strategy behind the famous catchphrase of Bill Clinton’s 1992 campaign, “it’s the economy, stupid.” And it was Greenberg who, with his Macomb focus groups, helped create the mythology around the apostate Democrats of the American everywhere.

Macomb County was not the American everywhere, of course. It was overwhelmingly white, and its whiteness had everything to do with Detroit’s having become too Black. “Its residents were just working Americans who made their way to the suburbs,” Greenberg writes in Middle Class Dreams, making white flight sound like a Sunday drive in the country. That’s not to say he was inattentive to the racism of his subjects. On the contrary his dispatch from Macomb is remarkable in this respect, a portrait of racism as a constitutive element in the sense of dispossession felt by white workers. Greenberg writes: “Blacks constituted the explanation for their vulnerability and for almost everything that had gone wrong in their lives; not being black was what constituted being middle class; not living with blacks was what made a neighborhood a decent place to live.” It’s not just the economy, stupid.

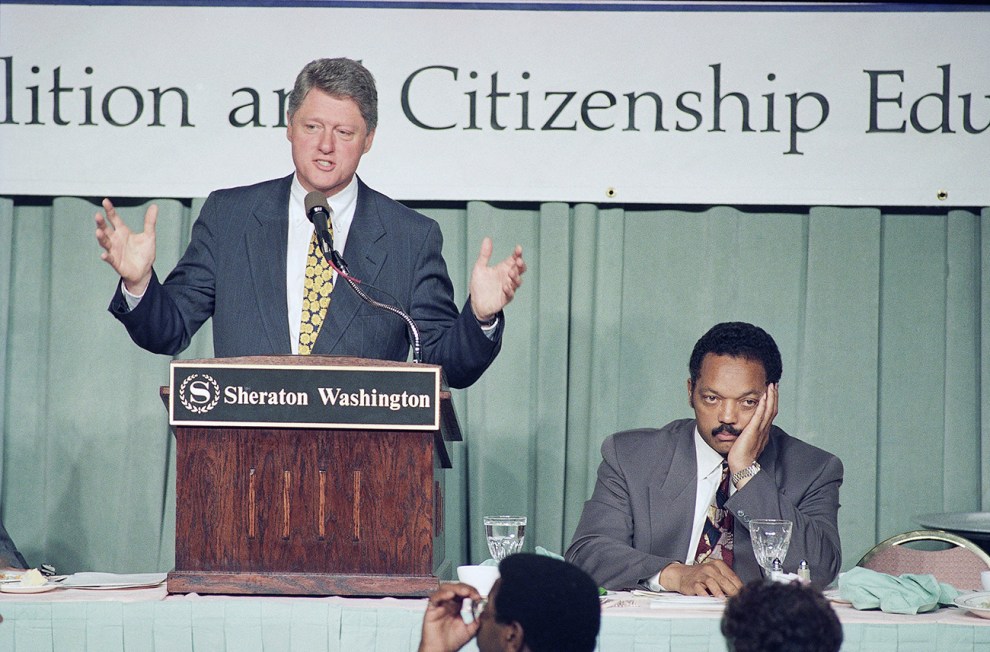

Bill Clinton has his “Sistah Souljah moment” at a conference held by Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition in June 1992.

Greg Gibson/AP

Greenberg was capturing an important moment in the rise of a newly configured authoritarian populism, though he was perhaps too indulgent of his subjects to see it clearly. Capital had pulled out of its mid-century bargain with labor and the government, bringing to a close the brief period of relative egalitarianism and giving way, in the 1970s, to the neoliberal paradigm in which workers were told to give themselves wholly over to the discipline of the market. The stalemate era had dawned. The state had retreated from its old assertive role, and for a great many workers government was now experienced—in the words of Stuart Hall, writing of the Thatcherite United Kingdom—not as “a beneficiary but a powerful, bureaucratic imposition. And this ‘experience’ is not misguided since, in its effective operations with respect to the popular classes, the state is less and less present as a welfare institution and more and more present as the state of ‘state monopoly capital’.”

In the US context, the process described by Hall—part of what he called “The Great Moving Right Show”—was fully racialized by many of the workers caught within it. Greenberg’s subjects told him as much. In their eyes the government was now the servant of the wrong people.

The Democratic party was reduced and narrowed by its association with free-spending government: “too many free programs too much spend, spend, spend.” That concern seemed less one of fiscal responsibility and more one of identity of interests. Whom did the party represent? With whom did it identify itself? There was a widespread sentiment, expressed consistently in the groups, that the Democratic party supported giveaway programs—that is, programs aimed primarily at minorities. This was no longer a party of great relevance to the lives of middle class Americans.

Federal government offices, in particular, were seen as a black domain, where whites could not expect reasonable treatment. If you applied for a job at the post office, “you may as well take the application and tear it up” because “there were twenty blacks behind you, but they will get the job.” The federal offices, they believed, were staffed by blacks—or “all minorities, blacks, Mexicans,…one white”—who act to the advantage of black applicants and customers.

Thus was blame for the shriveling of public provision assigned to the party of the interventionist state, the Democrats, now fully inhabiting their role as capitalism’s crisis managers. The turn of some workers against the state and its stewards—the result of a series of uncouplings and recouplings at the intersection of the cultural and the material—goes a long way toward explaining why a Floridian might vote for a $15 minimum wage but not for Joe Biden. The essential contradiction of social democracy under capitalism, as suggested by the quadrennial spectacle of Democrats offering themselves up as the party of both labor and big business, has been inscribed into the political attitudes of its would-be constituents.

Greenberg saw all this—up to a point. Watching as his subjects’ grievances began to fit themselves into a sort of common sense, he could see the populism at work but not the authoritarianism that gave it its form. He could ably describe the white identity politics of his respondents, but he could not or would not see how those politics were inextricable from the material demands of these members of the “forgotten” middle class with whom he empathized so completely. He seemed to share their hydraulic conception of political economy—anything for those people means less for us.

The insights Greenberg had gleaned from Michigan’s “Reagan Democrats” would go on to inform his political work. In 1992, he was part of the crew that came up with the Clinton campaign’s message. The slogan they arrived at with might as well have jumped off the page of one of Greenberg’s transcripts from Macomb. Here’s how he described it in a 2005 interview:

In fact, we had the overall message, but the—I’ve written about it, about what I called the Reich–[David] Osborne Solution, in which our message was “People First,” but it began with “Government is Failing,” and so it had a kind of an anti-government reform message as you then led into, “It ought to be a government that works for people.” It was a merger of—I presented that final integration of this, and these people were there. These people were part of the debate on getting this theme together, on how People First would work and how it would be a broader concept. He was speaking that day. I presented the thing at the hotel, and then he was going over to speak at the Rainbow Coalition where it was agreed he was going to say this.

Maybe you’ve heard of that speech. It was what we now call the “Sistah Souljah moment,” a signal culture-contra event wherein Clinton repudiated a Black cultural figure as a way of soothing the “economic” anxieties of white voters. This was as much a part of the campaign’s message as the slogan. They could say “people first” so long as it was clear that what they really meant was “some people first.”

On the day Pennsylvania was called for Joe Biden, I went to a park in West Oakland where a rookie politician named Carroll Fife was holding a rally to thank her volunteers, having pulled out to a decisive lead in her race for Oakland city council. Fife, a longtime activist, was one of the Black women behind Moms 4 Housing, a group that in 2019 staged a brazen occupation of a long-empty house owned by real-estate speculators. In a city with more vacant houses than unhoused people, with Black people constituting 70 percent of the homeless population, the group was claiming the home on the grounds that housing is a human right. In America this is such a controversial proposition that the sheriff’s office arrived with guns and a tactical vehicle when the time came to evict the moms. (A spokesperson for the Alameda County Sheriff’s Office later explained to the journalist Tammy Kim that the militarized response was necessitated by “anarchist and criminal elements” among the moms’ supporters, a little echo of John McClellan in the air.) The state quickly intervened, and a deal was struck whereby the speculators would agree to sell the house to the Oakland Community Land Trust, which would then lease the home back to the moms with the promise of keeping it affordable.

It was a victory for Moms 4 Housing, but it was something larger, too. What Fife and the moms had done was draw people into a politically meaningful confrontation along the overlapping dimensions of the cultural and the material, of identity and class—the very nerve of American politics. The shabby fundamental arrangements of the age of scarcity had been not just exposed but obliterated by the simple act of moving in. To watch the idea spread—to Minneapolis, where people turned a hotel into a sort of commune in the aftermath of the initial protests over George Floyd’s killing; to Philadelphia and Los Angeles, where families occupied vacant properties owned by public agencies—was to feel the buzzy sense of an overdue derangement to our politics, of something too long stuck beginning to come unbound.

Fife’s candidacy was as exciting to me as anything else on the November ballot. Nationally there was Biden, as pure a product of the stalemate as any politician alive. But here in Oakland’s District 3 a more emancipatory vision of politics was on the ticket. The rally in that park was at odds with the delirium of the moment, but in its way it was no less happy than all the dancing and honking nearby along Grand Avenue. Fife thanked her staff, and she spoke of the challenges ahead, of the streaks of red within the blue of California, of the reactionary turn that could be discerned in the ballot propositions, of neoliberalism and liberalism and housing and policing and climate.

Here on the page the list comes off like the grim setting of the jaw before battle, but that doesn’t quite capture the spirit of the thing. The litany alone was a joyful rebuke to the logic of stalemate, to its dreary hydraulics and zero sums. These were not discrete issues, each to be weighed carefully by its popularity among certain constituencies, each to be indexed to the sensitivities of certain voters. They were part of a story Fife had been telling, first through her activism and then by way of her political campaign. It was about race and but it was about class and but it was about culture, the all-at-onceness of oppression in America being met by necessity with the all-at-onceness of liberation.