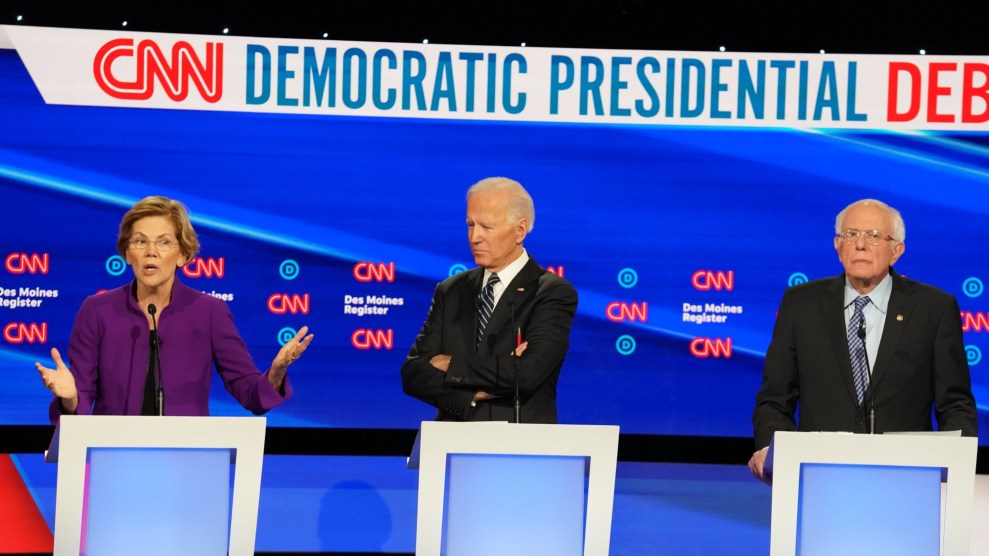

Carolyn Kaster/AP

As President-elect Joe Biden prepares to shape a national security team in his image, few choices loom larger than who he will pick to lead the Defense Department. That decision will help determine how sharply Biden’s foreign policy veers from the chaos of Donald Trump’s presidency—and how much it diverges from the progressive foreign policy ideals increasingly gaining sway within the Democratic Party.

Michèle Flournoy, an Obama Defense official with decades of experience in Washington national security circles, is the leading candidate for the top job. Her selection would be historic, giving the male-dominated Pentagon its first woman leader. But it would also be divisive among progressives. She serves on the board of a major defense contractor and co-founded a consulting firm that’s done business with companies in the tech and defense industries, raising concerns that her appointment would secure more influence for weapons makers. Her foreign policy views, especially on China, have also attracted scorn from antiwar leftists, who consider her excessively hawkish. (A spokesperson for Flournoy declined to comment on the record.)

Mainstream progressive organizations have not attacked her by name, but instead have suggested criteria for appointees that would implicitly exclude Flournoy. Last week, two influential progressive lawmakers, Reps. Mark Pocan (D-Wis.) and Barbara Lee (D-Calif.), wrote Biden a letter urging him to “commit to appointing Secretaries of Defense with no previous ties to defense contractors.” Kate Kizer, policy director at Win Without War, a progressive foreign policy organization, similarly argued this week for a standard that nominees like Flournoy could not meet. “In an ideal world, no political appointees would have worked for or served on the board of a for-profit entity that received money from the agency they would work in,” she wrote in a piece published by the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, an organization that advocates for military restraint. She noted, however, that such a requirement might be “near impossible” for some potential Biden appointees to meet and added that in those cases, officials should be required to publicly disclose their past clients and recuse themselves from “decisions that would affect previous clients, employers, or corporations in which they have a previous financial interest.”

Win Without War and other antiwar advocacy groups—many of which are located in Washington, DC, and interface regularly with Congress and the Defense Department—have avoided taking on Flournoy directly. Other, more radical, organizers have been more willing to openly oppose her nomination. Ahead of the Democratic National Convention, Marcy Winograd, a California delegate for Bernie Sanders, distributed an open letter that asked Biden “not to rely on foreign policy advice from those who may have a conflict of interest as a result of their relationships and lobbying on behalf of merchants selling weapons and surveillance technology.” The letter, which was signed by nearly 500 DNC delegates, cited Flournoy by name alongside other veterans of the Obama administration, such as Antony Blinken and Samantha Power, as unsuitable appointees.

Among the harshest of Flournoy’s critics is CODEPINK, an antiwar group that rose to prominence in the post-9/11 era by disrupting congressional hearings and building a grassroots network of local activists. In recent weeks, CODEPINK and its allies have mobilized their network of supporters through petitions and a letter-writing campaign to oppose Flournoy’s possible nomination. “President-elect Joe Biden is expected to select notorious war-hawk Michele Flournoy, who supported the wars in Iraq, Libya and Syria when she worked at the Pentagon and is on the board of military IT contractor Booz Allen Hamilton, as his candidate for Secretary of Defense,” reads one petition put forward by the group. “Contact your Senators right now and tell them: no weapons industry war-hawks in the President’s cabinet!”

But for other progressive foreign policy groups, the decision to devote resources and attention to opposing Flournoy is knotty, even if her views and professional background are unpalatable to them. The apparent likelihood of her nomination is one complicating factor, as is the awkward optics of progressive activists lining up to challenge the first woman nominated to be Defense secretary. Then there’s the question of whether it’s worth wrecking relations with the Biden team at such an early moment, when all signs point to the administration being amenable to an exchange of ideas with progressives. “Are you really willing to go scorched earth, use up all the political capital we have on frankly what is, by every indication, a losing battle?” one leading progressive activist told me.

The Biden team is certainly aware of concerns about Flournoy. The Intercept had reported on her consulting work as early as 2018, and a July story from the American Prospect, headlined, “How Biden’s Foreign-Policy Team Got Rich,” drew attention to the firm she co-founded with Blinken, one of Biden’s campaign advisers and a contender for a senior national security role in the administration.

In late September, during one of several calls between Blinken and progressive foreign policy activists, Flournoy was mentioned as an example of a nominee who would provoke concerns, according to a participant on the call. Evidently aware of the need to preempt criticism from the left, Flournoy herself convened a call with leaders from progressive and antiwar groups on October 28, details of which were first reported by Politico. On the call, which a participant described to me, Flournoy raised the issue of American support for Saudi Arabia’s war in Yemen, a conflict that’s devolved into the world’s worst humanitarian crisis. The Obama administration started the policy of giving military support to the Saudis as part of the conflict, but several national security officials from that era, including Biden himself, have since repudiated that decision. During the October call, Flournoy also discussed the military’s use of drones, civilian casualties in overseas conflicts, and the defense budget, which progressives have long campaigned to slim down.

That call portends the start of a civil, if often disagreeable, relationship between Flournoy and antiwar groups in Washington, which grew used to finding much to criticize about the Trump administration and now faces a different, more amenable, Defense Department that will likely still promote policies that are anathema to what the community supports. Even as grassroots organizers are clamoring to take on Flournoy, progressive leaders seem intent on lowering the temperature of a potential clash.

I saw this dynamic play out on Tuesday night, during a Zoom meeting involving Winograd, CODEPINK, and members of several other peace-focused groups. The event featured Matt Duss, foreign policy adviser to Sanders, and was promoted with the tagline: “Want to help pressure Biden on foreign policy?” Few folks would be better equipped to do that than Duss, who helped organize a bipartisan coalition in Congress to support a war powers resolution, which would have restricted Trump’s ability to support the Saudi war in Yemen without congressional approval. The resolution passed in a historic vote, but Trump vetoed it.

During the call, Duss was asked if Sanders, or other lawmakers, had interest in blocking Flournoy’s potential nomination. He deflected, saying he “really can’t comment,” and urged activists to “start with the commitments President-elect Biden and the Democratic Party have made” and “start with the assumption that that’s what they’re going to follow through on.” It’s true that Biden has moved left on certain foreign policy issues and has permitted progressive ideas like “ending forever wars” to enter the party platform. But he remains at odds with the left on some crucial issues, including how to address Israel’s treatment of Palestinians.

Foreign policy is not subject to the same congressional constraints as other domestic issues important to progressives, such as economic policy or health care. But even as Biden has more sway in that realm in the near future, progressives say they’re focused on the long game. “When we started thinking about the next Administration, we realized that the real change we want to see is going to take time,” Stephen Miles, executive director of Win Without War, told me. “And when you’re thinking about and building towards the next, next administration, that’s going to shape how you approach the next four years, where you choose to fight, where you focus on progress, and ultimately where and how you build power.”

Outstanding questions still remain about Flournoy’s ties to the defense industry, and some lawmakers and activists will no doubt raise them during any potential confirmation process. The Prospect reported in July that WestExec Advisers, the firm co-founded by Flournoy and Blinken, has a “defense prime” as a client—that is, one of the large defense firms, such as Raytheon or Lockheed Martin, that does business with the federal government. When I asked WestExec over the summer about disclosing its client list, a spokesperson said that nondisclosure agreements “prevent us from publicly listing our clients.” This week, in response to a question about Flournoy and Blinken (who is currently on leave from the firm) possibly joining the Biden administration, a spokesperson said the firm “will fully comply with the law and any disclosure requirements.” Mandy Smithberger, a defense analyst at the Project on Government Oversight, which has criticized the Pentagon’s revolving door with industry, said “it’s rare” for nominees in a similar position to Flournoy to proactively name their clients. “That will take pressing through the confirmation process,” Smithberger said.

Some progressive groups say they’re up to the task of pushing Flournoy on this, even if they expect she will ultimately be nominated and confirmed.

“While many progressive organizations may be reluctant to publicly oppose Michele Flournoy’s nomination given the likelihood that she would be confirmed, we do however expect our allies in the Senate during the confirmation process to seek clarity with respect to who her clients were at WestExec, which programs she specifically worked on, and whether she would be willing to recuse herself especially if she worked on major weapons programs,” Yasmine Taeb, a senior fellow at the Center for International Policy, said in a statement. “It’s important to shed light on what Flournoy previously did, and if those former clients will have an expectation that they’ll have a leg up with her as Defense Secretary.”

Winograd, for her part, wishes the media would focus on candidates other than Flournoy. “I personally called Sen. [Tammy] Duckworth’s (D-Ill.) office to encourage her to go on television, though I certainly don’t agree with her insistence on keeping US troops in Afghanistan,” she told me. “I simply think the public deserves serious debate on the future of US foreign policy.”