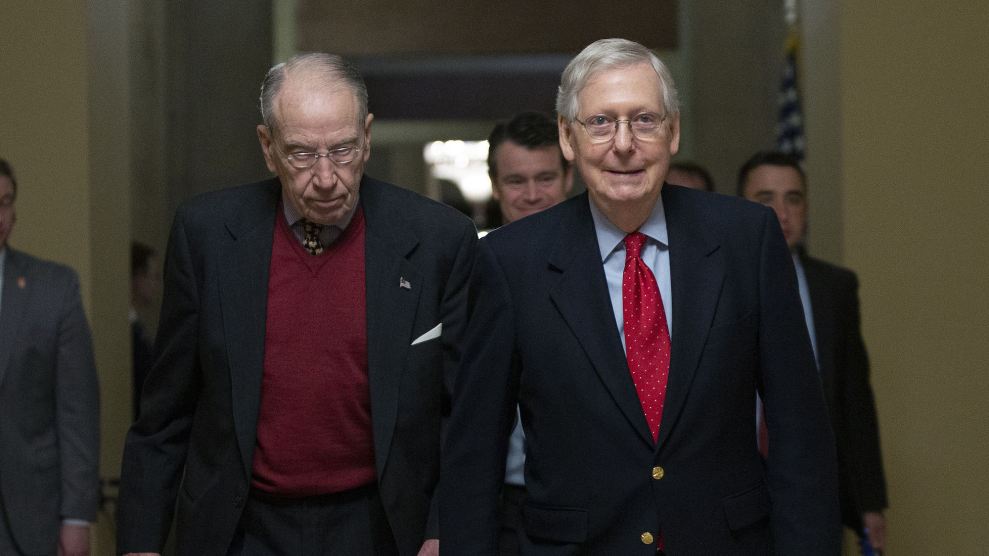

Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnellStefani Reynolds/ZUMA

After weeks of debate and delay, Republicans unveiled a summary of their proposal for a new coronavirus relief bill on Monday. And not only will millions of Americans see their weekly unemployment payments drop by hundreds of dollars if the proposal becomes law; they may not even get those payments for months.

The summary, shared by Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa), includes Republicans’ much-anticipated changes to the weekly $600 unemployment boost that has kept millions of jobless Americans afloat since Congress enacted it in March. It calls on Congress to cut the $600 weekly benefit to $200 through September. After that, states would have to pay unemployed workers 70 percent of the wages they made at their last jobs.

The plan will create layers of administrative headache that threaten to tax already strapped state unemployment systems even further, and to delay benefits for months, says Michele Evermore, a senior policy analyst at the National Employment Law Project.

In a memo circulated among lawmakers, the National Association of State Workforce Agencies (NASWA) warned that the plan would take state agencies between 8 and 20 weeks to implement. That clock would start ticking only after the bill is officially passed and the Department of Labor issues its guidance on how exactly the benefits should be distributed.

These long delays stem from the mechanics of unemployment insurance. When Congress first passed the weekly $600 unemployment boost in March, state labor departments had to reprogram their unemployment systems to dole out this additional money, which comes from federal, rather than state, coffers, and thus must be tracked separately, explains Evermore. Many states have now turned off that programming, given that the final week that workers were eligible for the extra $600 ended over the weekend. Still, state systems for doling out the same lump-sum payment to everyone now exist, and they could be reprogrammed to disburse $200 payments in a matter of weeks, notes the NASWA memo.

But this Senate proposal won’t allow state systems to simply return to flat payments. They’ll have to revisit individual unemployment recipients, calculate what constitutes 70 percent of their past wages, and program a way to dole out and track those distributions from two separate places: regular unemployment from state funds, and the rest of the payments from federal dollars.

“State unemployment systems are already so overwhelmed,” says Evermore. “Now we’re telling them, ‘By the way, you have to rework your system to pay benefits in a way that we’ve never paid them before, good luck.’”

The NASWA memo warned lawmakers that the requirement that payments be individualized for each recipient would cause delays. “[U]sing a calculation based on individual wage records will necessarily require additional time to program,” notes the memo.

This burden will come on top of a long list of challenges that is already bogging down state unemployment systems. First, states are facing record numbers of unemployment claims; more than 40 million Americans have applied for unemployment since the pandemic began. The latest Department of Labor data shows 1.4 million new claims were filed across the country during the week ending July 18.

The record numbers of claims have flooded state labor departments, some of which called in the National Guard to help process their unemployment backlogs.

On top of this, many states have had to apply additional layers of verification and red tape to unemployment claims, as they attempt to weed out sophisticated fraudsters who have tried to siphon off millions in US unemployment dollars by impersonating American workers. The result has been more work for these agencies, and paused or slow benefits for many recipients.

What’s more, as many people refuse to return to jobs due to coronavirus risk or caregiving responsibilities, state unemployment systems are faced with the additional work of verifying their reasons for not returning to ensure compliance with the terms of the expanded federal unemployment program. The program allows people who wouldn’t otherwise be eligible for regular unemployment to qualify when they’re not working for a number of virus-related reasons. The Labor Department has recently asked dozens of state agencies to verify that their recipients still qualify for the benefit.