JazzIRT/Getty

This story was published originally by ProPublica, a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up for ProPublica’s Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox as soon as they are published.

In 2017, TeamHealth, the nation’s largest staffing firm for ER doctors, sued a small insurance company in Texas over a few million dollars of disputed bills.

Over 2 1/2 years of litigation, the case has provided a rare look inside TeamHealth’s own operations at a time when the company, owned by private-equity giant Blackstone, is under scrutiny for soaking patients with surprise medical bills and cutting doctors’ pay amid the coronavirus pandemic.

Hundreds of pages of tax returns, depositions and other filings in state court in Houston show how TeamHealth marks up medical bills in order to boost profits for investors. (Some of the court records were marked confidential but were available for download on the public docket; they were subsequently sealed.)

TeamHealth declined to provide an interview with any of its executives. In a statement for this story, the company says it’s fighting for doctors against insurance companies that are trying to underpay: “We work hard to negotiate with insurance companies on behalf of patients even as they unilaterally cancel contracts and attempt to drive physician compensation downward.”

But the Texas court records contradict TeamHealth’s claims that the point of its aggressive pricing is to protect doctors’ pay. In fact, none of the additional money that TeamHealth wrings out of a bill goes back to the doctor who treated the patient.

Instead, the court records show, all the profit goes to TeamHealth.

“These companies put a white coat on and cloak themselves in the goodwill we rightly have toward medical professionals, but in practice, they behave like almost any other private equity-backed firm: Their desire is to make profit,” said Zack Cooper, a Yale professor of health policy and economics who has researched TeamHealth’s billing practices and isn’t involved in the Texas lawsuit.

“In the market for emergency medicine, where patients can’t choose where they go in advance of care, there’s a real opportunity to take advantage of patients, and I think we’re seeing that that’s almost precisely what TeamHealth is doing, and it’s wildly lucrative for the firm itself and its private equity investors.”

Some of TeamHealth’s own physicians say they’re uncomfortable with the company’s business practices.

“As an emergency medicine physician, I have absolutely no idea to whom or how much is billed in my name. I have no idea what is collected in my name,” said a doctor working for TeamHealth who isn’t involved in the Texas lawsuit and spoke to ProPublica on the condition of anonymity because the company prohibits its doctors from speaking publicly without permission.

“This is not what I signed up for and this isn’t what most other ER docs signed up for. I went into medicine to lessen suffering, but as I understand more clearly my role as an employee of TeamHealth, I realize that I’m unintentionally worsening some patients’ suffering.”

Most ER doctors aren’t employees of the hospital where they work. Historically they belonged to doctors’ practice groups. In recent years, wealthy private investors have bought out those practice groups and consolidated them into massive nationwide staffing firms like TeamHealth and its largest competitor, KKR-owned Envision Healthcare.

These takeovers have affected patients, too, because the groups have gotten into payment disputes with their insurers. As a result, patients can receive huge medical bills even when they pick a hospital within their insurance plan’s network, because the individual doctor working for a contractor like TeamHealth could be out of network. This practice, known as surprise billing, caught the attention of lawmakers who have spent months working on legislation.

TeamHealth said surprise bills are “rare and unintended,” but with millions of patients, it has happened tens of thousands of times. The company has called surprise billing a “source of contracting negotiating leverage” to demand higher payments from insurers.

“Underneath this are patients who may well be charged outrageous amounts of money, but that’s just not a core consideration,” said Joshua Sharfstein, a professor of health policy and management at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. “The situation a lot of patients feel like they’re in is they’re collateral in this financial tug of war.”

TeamHealth and Envision Healthcare have poured millions into political ads attacking surprise billing legislation. The companies have said they want to settle out-of-network bills through arbitration instead of using average local rates, as some lawmakers have proposed.

As an alternative to going after patients themselves, TeamHealth said it sues insurers to demand higher payments for out-of-network charges. The company has filed 38 such lawsuits since 2018.

In the Texas case, two TeamHealth affiliates that provide doctors and nurses to emergency rooms in the Houston and El Paso areas sued a small insurance company called Molina Healthcare. TeamHealth identified almost 5,000 out-of-network claims in 2016 and 2017 for which it billed $6.6 million and Molina paid $760,000. TeamHealth sent a letter demanding that Molina pay $2.3 million. Molina’s lawyers viewed this as an admission that the original bill was far higher than even TeamHealth thought was fair.

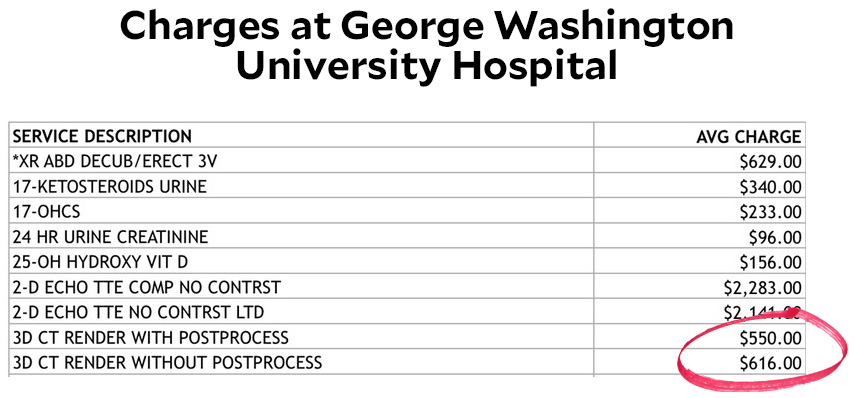

The actual costs of medical services are not a factor in setting TeamHealth’s prices, according to the deposition of Kent Bristow, a TeamHealth executive in charge of revenue. At some locations, TeamHealth’s prices were higher than those of 95% of other providers and eight or nine times more than what Medicare would pay, according to Bristow’s deposition.

Most of the two TeamHealth affiliates’ charges were never actually collected, according to their tax returns and a deposition of the accountant who prepared them. For the years 2016 and 2017, the two affiliates billed a combined $1.9 billion, the tax returns show. But $1.1 billion, or 58%, was discounted according to negotiated deals with insurers. An additional $528 million was written off as bad debt that would never get repaid. So the combined revenue that the two affiliates actually received across the two years was $274.5 million, or about 14% of the amount initially billed, according to the tax returns.

The amount that TeamHealth charges doesn’t determine how much TeamHealth pays its doctors who perform those services, the company’s chief financial officer, David Jones, said in an October 2019 deposition. Instead, the doctors are paid a base compensation plus an incentive tied to how much work they do (which is not the same as the price billed for their services). For the two TeamHealth affiliates in the Molina case in 2016 and 2017, the company paid doctors a total of $170.5 million, or 62% of the net revenue, according to the tax returns. Other health care providers such as nurse practitioners and scribes received another $48.4 million.

The administrative services that TeamHealth provides—such as billing, printing and malpractice insurance—added up to $29.5 million, according to the tax returns.

After covering all those expenses, the amount of money left over—commonly called profit—was $26.1 million, about 10% of the two affiliates’ net revenue in 2016 and 2017. (The accounting method that TeamHealth uses for its tax returns is different from how it prepares financial statements regulated by the Securities and Exchange Commission. Under the latter method, the tax returns note a total of $36.8 million for the two affiliates in 2016 and 2017. Because of these accounting variations, it’s impossible to compare the figures on the TeamHealth affiliates’ tax returns to profits reported by publicly traded health care companies.)

The TeamHealth executive in charge of the two affiliates said he assumed the profit would be shared with the doctors who did the work. “It would most likely go back to the providers,” the executive, Lance Williams, said in a deposition. Under further questioning, he admitted, “Yeah, I’m not sure.”

In fact, the entire leftover $26.1 million went to TeamHealth’s “management fee.” The management fee is not a fixed rate but rather everything that remains after covering costs, regardless of the amount, according to the CFO’s deposition. “If the revenues exceed the expenses, that is essentially the management fee,” Jones said.

In other words, out of the $1.6 billion that was originally billed but not collected, any additional dollar that TeamHealth managed to recover would be passed through to the corporate parent. The doctors would not see it.

Jones said doctors benefit from increasing collections because their incentive-based pay is adjusted over time. In addition, Bristow said the management fee is not the same as profit because there may be additional expenses at the corporate level.

“The economic benefits created by these practices, any profit, if you will, ultimately flows up to the TeamHealth entity,” Ron Luke, a health economics expert hired by Molina, said in a deposition.

To establish this business model, TeamHealth had to find a way to deal with long-standing state laws that were specifically designed to protect the medical profession from becoming beholden to profit motives. These laws, known as the corporate practice of medicine doctrine, require doctors to work for themselves or other doctors, not lay people or corporations like TeamHealth. Court records in the Molina case show how TeamHealth’s lawyers use shell entities to avoid directly employing doctors.

“TeamHealth monetizes this process by unilaterally setting charges and then billing patients and payors for those amounts and retaining all of the profits of the enterprise,” Robert McNamara, a former president of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine, wrote in a memo as an expert witness against TeamHealth in the lawsuit. “The fees generated, billed, and retained by TeamHealth reflect the type of overt commercialization of the medical profession that the prohibition on the [corporate practice of medicine] is designed to prevent.”

TeamHealth said its business arrangements comply with all laws and no court or agency has ever found otherwise. “TeamHealth’s clinicians are supported by a world-class operating team that provides them with comprehensive practice management services that allow our clinicians to focus on the practice of medicine,” the company said. Envision Healthcare also said it follows all local, state and federal laws and regulations.

State laws against the corporate practice of medicine date as far back as the 19th century, as doctors strove to distinguish themselves from quacks and snake oil salesmen. According to the American Medical Association, the laws are meant to prevent profit motives from influencing medical judgments—a recognition that corporations’ devotion to shareholder value shouldn’t mix with doctors’ Hippocratic oath.

Another way to think about it is: Practicing medicine requires a license, and only a real human being can possibly have the education, training and character qualifications that licensing boards require.

Courts have scrutinized these arrangements for decades. No judge has ever ruled that TeamHealth or Envision Healthcare specifically violate state licensing rules. But such allegations have repeatedly cropped up in lawsuits involving the companies, some of which settled favorably to the other side, according to McNamara, who was consulted on many of the cases.

TeamHealth and Envision have themselves acknowledged that they operate on questionable legal ground. During periods when the companies were publicly traded, their investor disclosures highlighted the controversy surrounding their compliance with state licensing regimes. TeamHealth and Envision said they believed their business models were legal but recognized that prosecutors, regulators and judges could conclude otherwise. TeamHealth specifically cited “laws prohibiting general business corporations, such as us, from practicing medicine.”

“While we believe that our operations and arrangements comply substantially with existing applicable laws relating to the corporate practice of medicine and fee splitting, we cannot assure you that our existing contractual arrangements, including restrictive covenant agreements with physicians, professional corporations and hospitals, will not be successfully challenged in certain states as unenforceable or as constituting the unlicensed practice of medicine or prohibited fee splitting,” the company said in its 2015 annual report. “In this event, we could be subject to adverse judicial or administrative interpretations or to civil or criminal penalties, our contracts could be found to be legally invalid and unenforceable or we could be required to restructure our contractual arrangements with our affiliated provider groups.”

TeamHealth says the laws are outdated and unnecessary—as one of the company’s senior lawyers called it in a deposition, “this arcane law we call the corporate practice of medicine that nobody needs.”

Not all states have such laws. In Florida, for instance, TeamHealth employs doctors directly. In states that have laws against the corporate practice of medicine, TeamHealth has a workaround depending on the specific requirements in that state. Here’s how it works for the affiliates involved in the Molina litigation, just two out of hundreds of equivalent arrangements around the country.

Doctors working for TeamHealth are technically independent contractors to a “professional association,” or P.A. In order to comply with Texas law, the professional association is owned by a licensed physician. The professional association then contracts with TeamHealth subsidiaries to provide administrative services—such as billing, payroll and malpractice insurance—in exchange for payment.

These professional associations, however, are hardly independent. They’re “owned” by an executive at TeamHealth, and the company has the power to remove and replace him at any time. For the two professional associations involved in the Molina case, when a new executive took over as “owner” in 2019, he said in a deposition that he couldn’t remember how he “bought” the entities or if he ever paid anyone the $2 nominal price of their shares.

“Everything about your right to own, operate, and manage ACS and EST [the two professional associations] is dependent upon you staying in the good graces of the TeamHealth organization, correct?” Molina’s lawyer asked in the deposition.

“Correct,” the owner/executive, Lance Williams, said.

“And if you were fired for any reason, you would lose ownership of ACS and EST, lose the right to manage ACS and EST, correct?”

“Correct.”

Williams also said there’s no “black and white” separation between clinical and financial issues.

In sum, the contract between TeamHealth and the professional associations gives investors more control of the business than doctors, according to Chuck Pine, a financial investigator who specializes in examining shell companies to determine the real beneficial owners. Pine isn’t involved in the Molina litigation.

Molina’s lawyers called the arrangement “a sham to permit TeamHealth to unlawfully practice medicine by allowing it to in effect employ physicians in violation of state law.”

TeamHealth countered that whether or not Molina’s claims are right, they aren’t enforceable through private litigation; only the state’s attorney general could prosecute a corporation for practicing medicine without a license.

The judge rejected Molina’s claims in an order that didn’t explain her rationale. Other parts of the case are still pending.

TeamHealth has used the same argument to defeat other lawsuits. It puts opponents in a Catch-22: State licensing boards have no control over a corporation that might be practicing medicine without a license because the boards don’t license corporations. The boards could theoretically punish the “owners” of the professional associations, but those doctors are not always licensed in the same state as the practice, and TeamHealth could always replace them with someone else.

The Texas attorney general’s office didn’t respond to requests for comment. McNamara said he’s brought several cases to the attention of various state attorneys general, to no avail.