Neal Waters/ZUMA

On Tuesday, Wisconsin Republicans forced residents to leave their homes and trudge to polling places. Photos of mask-wearing voters attempting to social distance in long lines brought home the reality of the dangers and difficulties of conducting in-person balloting amid a deadly pandemic.

While the hope of avoiding such scenes has inspired states to explore expanding or instituting voting by mail, and motivated Congressional Democrats to reportedly look to include funding and mandates to increase mail voting in their next coronavirus aid package, it could be a big lift for election officials to get such systems established in time for later primaries—or for this November’s general election. Even in places where a lot of people already vote by mail and the infrastructure is more or less in place, there are key obstacles to overcome such as logistics, supply chains, and perhaps the thorniest of all: politics.

Take Arizona. On March 18, a day after Arizona went ahead with its scheduled presidential preference primary, Secretary of State Katie Hobbs, a Democrat, asked the legislature to pass a law that would, if public health conditions require it, allow counties to run mail elections in November where every registered voter would automatically be sent a blank ballot. The response was unenthusiastic, with the Republican-controlled state legislature declining to formally address her request as GOP lawmakers accused Democrats of trying to use the pandemic to game election policy, while arguing it was already easy for the state’s voters to get mailed ballots and claiming that vote-by-mail was prone to fraud, more expensive, and could delay results.

“The expressed reasons for opposition are false and not based in fact,” says Grant Woods, who served as Arizona’s Republican Attorney General from 1991 to 1999 before switching parties after President Trump’s election. “The real reason is they believe the lower the turnout, the better their chances.”

While Arizona is not among the five states that already conduct elections by automatically mailing all voters ballots, it does have widespread voluntary postal voting. About 70 percent of the state’s citizens have put themselves on something called the Permanent Early Voter List, which means they get a blank ballot sent to their address before every election. In the 2018 midterm elections, according to state and federal data, roughly 78 percent of all ballots cast in Arizona—about 1.9 million votes—were mailed in, representing both voters on the list and others who, up to 11 days before the election, requested a one-time postal ballot.

Those numbers represent a huge advantage over other states that may be interested in spinning up a universal vote by system from scratch before November. But the Arizona legislature’s failure to embrace Hobbs’s proposal shows that longstanding opposition, typically on the part of partisan Republicans, to vote-by-mail and other policies designed to increase poll access hasn’t softened even as public health officials advise against public gatherings.

“If they won’t do it in these circumstances, they’re not going to support it,” Woods said. “They think they need to do whatever possible to stay in office.”

Hobbs told Mother Jones that the request she made to the legislature was on behalf of a bipartisan group of county election officials, and would only establish new rules for this year’s elections, not permanently. The changes she’s outlined would give local officials, after sending ballots to all voters, more flexibility over in-person voting, including the possibility of setting up fewer in-person voting sites for those who still wish to vote at a polling place, and which can double as ballot drop off centers.

“We can’t be under a stay-at-home order and ask people to go out and risk their lives to vote,” Hobbs said. “We can’t just act like everything’s normal when it comes to elections. We can’t. It’s unprecedented. It is just absolutely asinine to me that this has become a partisan response.”

Republicans, in pushing back on vote-by-mail initiatives, have argued that election administration has nothing to do with coronavirus response—even as poll workers and election office workers have gotten sick and died.

Trump, who himself most recently voted via a mail ballot, is urging Republicans to “fight very hard” against calls for increased mail voting. On Wednesday, he tweeted that the method has “[t]remendous potential for voter fraud,” and that “for whatever reason, [it] doesn’t work out well for Republicans.” Trump had previously said that Democrats’ proposals for increased access to ballots during the pandemic would mean “you’d never have a Republican elected in this country again.” Other Republicans around the country have also said that more mail voting will hurt GOP candidates.

Last week, Rep. Shawna Bolick, a Republican legislator in the state House of Representatives, wrote an op-ed offering a litany of reasons why she and her colleagues didn’t address Hobbs’s request. While she acknowledged that Arizona voters can already opt-in to voting by mail, she argued that it is the “most complicated” of any method of voting in the state, is expensive, lends “itself to fraud and confusion,” requires more staffing, and slows down counting.

“A knee-jerk reaction to move to a mail-only election would lead to lengthy tabulation scenarios compromising the integrity of our elections,” she wrote, claiming that a vote-by-mail system would “reduce our voting options to just one.”

On Wednesday, two county election officials who are actually responsible for conducting elections teamed up to write a column rebutting Bolick’s arguments. In a piece titled “We Run Elections in Arizona. An All-Mail Option for 2020 Wouldn’t Ruin the Process,” Virginia Ross, the Pinal County recorder and president of the Arizona Recorders Association, and Lisa Marra, the Cochise County elections director and president of Elections Officials of Arizona, argued that Bolick had offered “inaccurate and often misleading information” about mail elections. They pointed out that Bolick’s argument that mail-elections would give voters just one option is not true: many in-person sites would still be open under the process envisioned by the organizations they represent, along with places to get replacement ballots and drop them off. They also report that mailing ballots to voters is “less complicated and less expensive compared to the massive logistical undertaking of finding, staffing, equipping, testing, sanitizing and maintaining hundreds of voting locations across the state.”

“This is about people, not politics, and we respectfully renew our call to Rep. Bolick and the rest of the Legislature to allow us to conduct accurate, secure and safe ballot-by-mail elections this year,” they wrote.

Jennifer Marson, the executive director of the Arizona Association of Counties, echoed Ross and Marra in saying that recruiting the 16,000 volunteers the state needs to run polls would be a major issue for county election officials in a time of pandemic. They also have to secure voting locations even as the owners or managers of those sites—whether private or government—are increasingly reluctant to host large gatherings. “You can imagine how those conversations are going,” she said. “Both of those questions are very difficult to ask right now.”

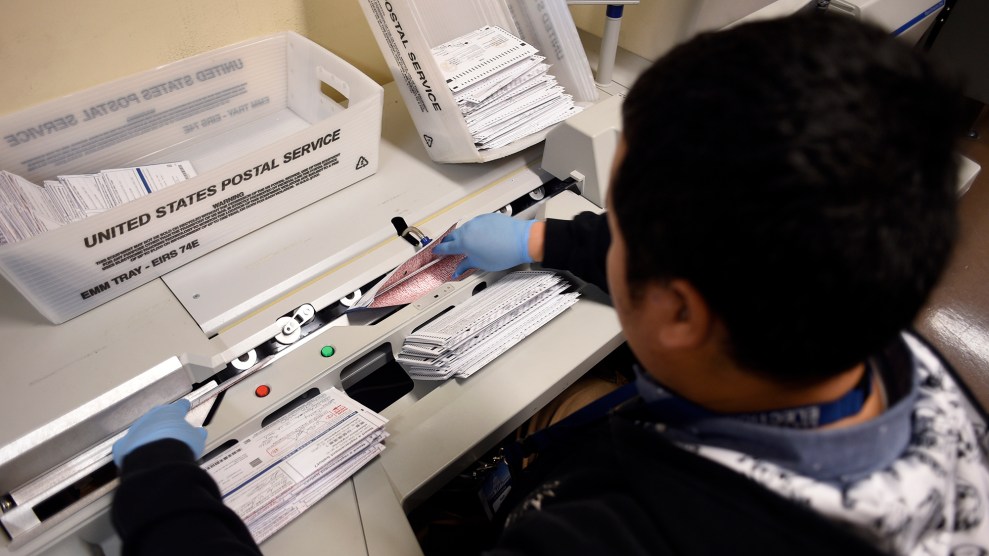

But in order to switch to vote-by-mail elections and reduce in-person sites, election officials are facing a closing window to procure materials like specialized ballot paper, envelopes, and sorting equipment, Marson said. Realistically, according to county election officials’ evaluation of supply chain timelines, the decision to switch needs to be made by April 15 for Arizona’s August 4th primary election for state offices, and no later than June 15 for the November general election.

Hobbs said along with the partisan pushback, another big problem is bridging the gap between politicians who may not appreciate the complexities of running elections and elections officials who insist that mail voting can be done safely, securely, and efficiently with adequate backing. While some local officials have been pressing state representatives for their support, if the legislature fails to act, counties are considering mailing all registered voters applications to become permanent mail voters and mounting a sustained public education campaign to encourage voters to sign up. A court battle could be a last-ditch resort—”but that’s not been working out very well,” she said, referring to how last minute efforts to delay voting or absentee ballot return deadlines in Wisconsin were stymied in state and federal court.

“I don’t have a lot of optimism about the legislature, but that doesn’t mean that we should stop making the case,” she said. “I think at this point it’s irresponsible of them not to take it up.”