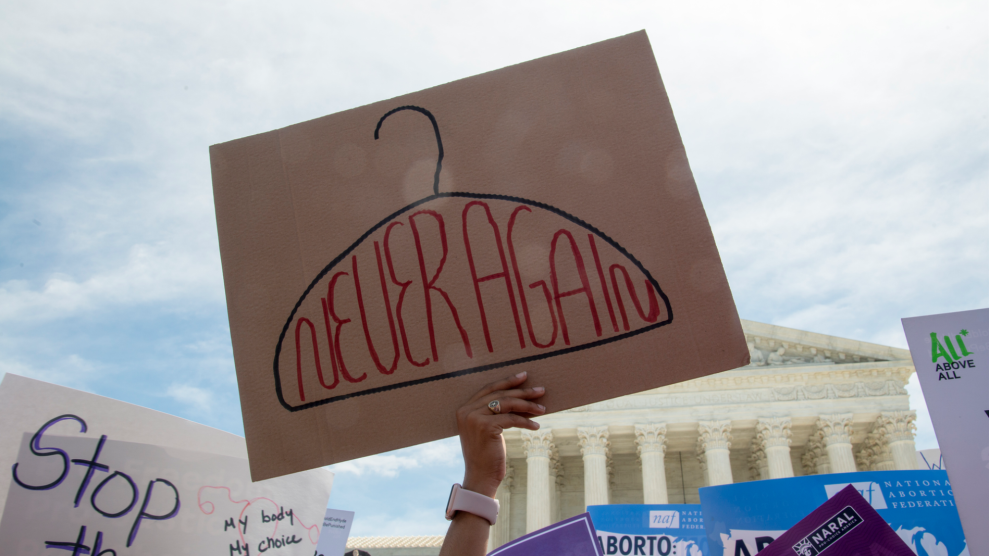

Anti-abortion marchers and abortion-rights supporters at the U.S. Supreme Court on the anniversary of Roe v. Wade in January 2005.Pete Souza/TNS via ZUMA Wire

On Wednesday, the Supreme Court heard is first abortion case since President Trump’s appointments of conservative justices Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh. Despite the court’s new conservative majority, the morning’s oral arguments left little clarity about its future verdict in a case that could determine abortion rights for years to come.

A ruling against the abortion clinic in the case on either the substantive or procedural issues at hand could gut access to reproductive health care across the country. Chief Justice John Roberts’ questions to lawyers on both sides indicated he was conflicted about how he would rule on the substantive issue.

The substantive issue in June Medical Services v. Russo involves a stayed 2014 Louisiana law requiring doctors to have admitting privileges at a hospital within 30 miles of the clinic where they provide abortions. The law is almost identical to a Texas measure that the Supreme Court ruled unconstitutional in the 2016 case Whole Women’s Health v. Hellerstadt as placing an “undue burden” on women seeking abortions by forcing many clinics to shut down without a justifiable health purpose. On Wednesday, the court’s liberal justices hammered Louisiana’s attorneys over why admitting privileges were necessary for a procedure with a low complication rate, and specifically what benefit the 30 mile requirement plays when many women safely take medication to induce an abortion at home.

Lawyers from the Center for Reproductive Rights representing June Medical Services argue that if the law were to go into effect, there would be only one doctor left in Louisiana who could provide abortions. Mary Ziegler, a professor at Florida State University who studies the history of abortion law, says upholding the law could prompt a “cascade” of similar restrictions in conservative states.

But the procedural issue could have an even further reaching impact. In 1976, the Supreme Court held that providers were eligible to represent their patients under a doctrine known as third-party standing. In this case, Louisiana challenged that precedent in a last-minute counter-petition, arguing that patients and doctors might not have the same interests, and that there isn’t necessarily a barrier to women bringing these cases themselves. Justices Kavanaugh and Samuel Alito seemed receptive to the argument, opening the door to a ruling that would force individuals denied or blocked from seeking abortions to bring a federal case on their own, a daunting legal and financial proposition for people already navigating an unwanted pregnancy. Such a decision could force women to delay getting an abortion until after filing suit in order preserve their individual standing to sue, and push them into waging legal battles that could last for years, long after their own pregnancies were over.

If the court strikes down third-party standing, states may feel freer to pass tight abortion restrictions, knowing that lawsuits against them are less likely. Patient privacy could also be lessened, with individual plaintiffs forced into the public spotlight. “There’ll be demonstrations against them,” says Stephen Wermiel, a constitutional law professor at American University. “We’re not talking about the shy and retired demonstrators. We’re talking about people holding up posters with pictures of dead fetuses shouting, ‘Baby killer!’”

Trump’s appointees have created the most conservative bench in decades, turning court watchers’ eyes on Roberts, the presumptive swing vote. While the chief justice joined an anti-abortion dissent in Whole Women’s Health, last year he issued an injunction preventing the Louisiana law from going into place, actions placing him on both sides of the issue.

In his time leading the court, Roberts has projected a desire to preserve the courts public legitimacy by deferring on occasion to longstanding decisions. Roberts could decide that overturning a nearly 50-year-old precedent by rejecting third-party standing could run against that, says Wermiel, adding the caveat that Roberts is hardly a moderate on abortion.

During Wednesday’s hearing, Roberts raised several pointed questions about whether there were differences in the benefits of requiring admitting privileges between Louisiana and Texas, though he refrained from asking about third-party standing—which could indicate he is less open to the possibility of ending the practice. But analysts of the court warn against anticipating any case’s outcome based on oral arguments.

“This is probably the most unpredictable the Supreme Court has been on abortion in decades,” says Ziegler.