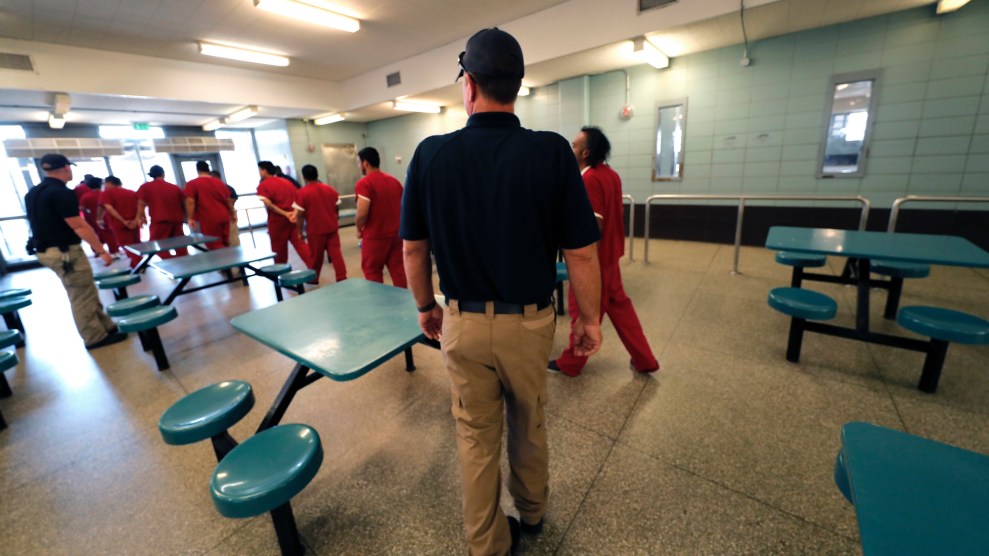

Detainees leave the cafeteria under the watch of guards in September at the Winn Correctional Center, a for-profit prison in Louisiana used by Immigration and Customs Enforcement.Gerald Herbert/AP

As Lázaro Siberio-Pérez, a Cuban asylum seeker, tells me about being pepper-sprayed yesterday by guards at an immigration detention center, he is wearing only underwear. His clothes, he says, are too painful to put back on, even now. They remain doused in the “spray,” he says, switching from Spanish to English, and he hasn’t yet been issued another set.

Siberio-Pérez is not alone in his pain. Bryan Cox, an Immigration and Customs Enforcement spokesman, confirms in a statement that seven people were pepper-sprayed on Tuesday at a Pine Prairie, Louisiana, detention center, a for-profit facility run by the private prison giant GEO Group.

Tuesday’s use of force comes as tensions build within ICE detention centers across the country and detainees crammed into facilities fear contracting the coronavirus. On Monday, about 60 people were pepper-sprayed at another GEO Group ICE detention center in Texas after they demanded to be released to protect them from the virus, the San Antonio Express-News reported. ICE announced on Tuesday that a detainee in New Jersey had tested positive for COVID-19, the first confirmed case in its custody.

Homero López, the executive director of ISLA, the legal aid group representing Siberio-Pérez, says the Pine Prairie incident began in the afternoon, when guards asked the seven detainees to leave their shared cell to go outside. They took it as a sign that something bad was about to happen to them; Siberio-Pérez says that guards take out small groups like this when they want to do things like transfer people to solitary confinement.

The detainees refused to go outdoors, and people in other cells started to protest when they saw what was happening, López says. Guards soon arrived wearing riot gear. Siberio-Pérez says they then hit and pepper-sprayed him and his cellmates. A second Cuban man tells me he couldn’t breathe after being pepper-sprayed, adding that he felt like he was burning from within. (Cox says in his statement that the detainees became “physically combative” while refusing to go outside, adding that they “became compliant” after pepper spray was deployed.)

Jacyln Cole, a paralegal at the Southern Poverty Law Center, confirms she heard about the episode from another Pine Prairie detainee, who called her around 5 p.m. on Tuesday while people were being pepper-sprayed. The man told her he could see about eight guards in riot gear, as well as an assistant warden.

Most or all of the people who suffered from the pepper spray were then moved into isolation cells, which ICE detainees refer to in Spanish as “holes” or “the well.” Siberio-Pérez says he hasn’t been given any essential supplies—a toothbrush, toothpaste, toilet paper—since being transferred to a two-person cell on Tuesday. At first he was on his own in the cell; he says he spent Tuesday night alone and cold, since he couldn’t wear his clothes. (There also aren’t sheets on the beds, according to one of the people moved into isolation on Tuesday.) Guards brought a second person, a Cuban doctor, to join Siberio-Pérez in his cell on Wednesday. Siberio-Pérez says he’s been told he’ll spend one to three months there, isolated from the detention center’s general population.

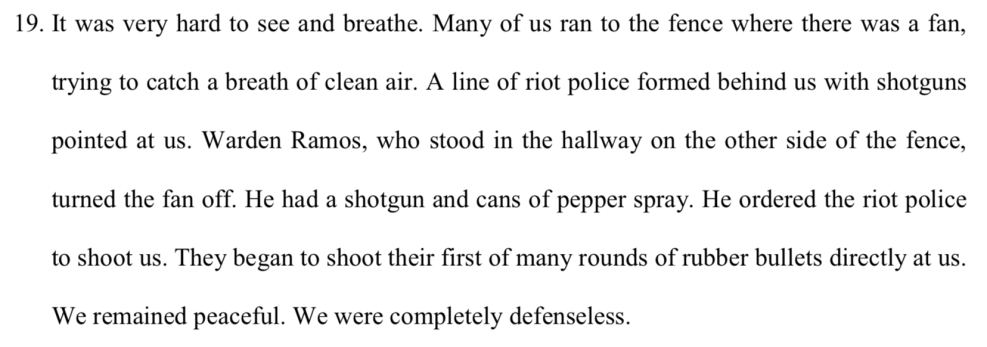

This is not the Pine Prairie facility’s first reported incident involving pepper spray and detainees; in August, more than 100 people there were pepper-sprayed, BuzzFeed News reported at the time. One of those detainees said in a court declaration that the group had been peacefully protesting ICE’s refusal to release them while their cases are pending, a practice that a federal judge later found violates the agency’s own parole policy.

“[The warden] began spraying our faces with pepper spray from no more than fifty centimeters away from us,” the man said in the declaration. “He used so many cans of pepper spray, I lost count. Officers continued to throw gas bombs and fire rubber bullets at us from all sides.” Here’s an except from that man’s statement:

As the new coronavirus spreads, health experts and immigrant advocates are calling on ICE to release people from detention who don’t pose a threat to public safety. ICE has refused to do so. On Wednesday, the Southern Poverty Law Center and other groups filed an emergency motion to try to force ICE to identify the people in its custody who are most vulnerable to the new coronavirus so that the agency can come up with a plan to protect them or let them out.

Louisiana, where the Trump administration has concentrated thousands of asylum seekers, is emerging as a new coronavirus hotspot. Democratic Gov. John Bel Edwards cited a study on Wednesday showing that Louisiana now has the fastest growing rate of infections out of any state in the US or of any country. “There is no reason to believe that we won’t be the next Italy,” he said.

Some of López’s clients at Pine Prairie told him they saw people in hazmat suits remove a detainee a few days ago. One of the dorms at the detention center remains under quarantine, López says, though ICE has declined to tell López if the quarantine is related to the coronavirus. When I asked Cox about it last week, before the latest pepper-spray episode, he replied in general terms. “Cohorting,” he wrote, using ICE’s term for quarantines, “is being done at multiple facilities to preclude the potential spread of COVID-19.”

Siberio-Pérez, who is 28, says he was a wrestling coach and physical education teacher in Cuba. He entered the United States to request asylum in April by coming to an official border crossing. Like another Cuban asylum seeker I spoke to earlier this month, he compares the detention that’s followed to a kidnapping. “This is a kidnapping,” he says. “We are kidnapped by ICE.”