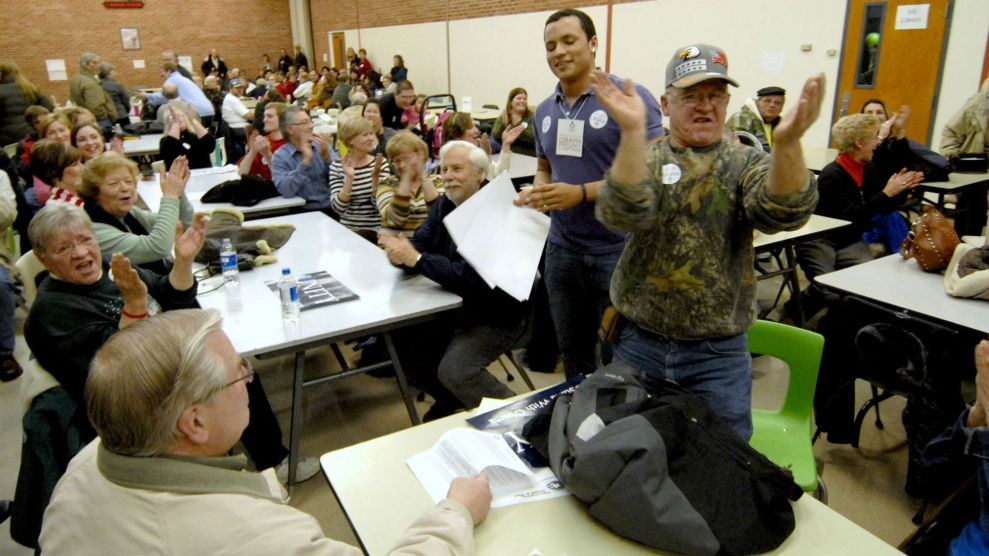

The phone app used for the Iowa caucuses.TNS/via Zuma

The traveling road show has moved on from Iowa, and the campaigns and most of the media circus that go with them have set up shop in New Hampshire. Still, the full results of the Iowa caucuses are not yet known. Numbers have been posted in spurts, and while the state Democratic Party and the designers of an app that was supposed to simplify the caucus-night results reporting process have withheld details about how and why the results were so delayed, they have issued apologies and pledged to figure out how they screwed up so badly.

While there’s been voluminous reporting trying to answer that question, for some security experts, the key lesson from Iowa’s meltdown is how the episode illustrates one of their biggest fears: bad actors seeking to interfere in an election don’t actually have to rig a voting machine or hack a voter registration database. They just have to make it look like they did, and chaos will be born and confidence lost.

Even though in Iowa’s case it seems that coding and management errors are behind most of the dysfunction, and not some nation-state hacker or malevolent political actor, “the outcome is the same regardless,” says Jordan Rae Kelly, a former senior FBI cybersecurity official who is now an executive at FTI Consulting.

“What we really saw in Iowa was the manifestation of [the idea that] you do not actually have to have a cybersecurity incident to really wreak havoc on outcomes in these types of situations. This isn’t just about building something that’s secure. It’s about building something secure and being able to prove in an unimpeachable way that it’s secure,” she says.

Even though Sen. Mark Warner (D-Va.), vice-chair of the Senate Intelligence Committee, has said publicly no hacking was involved, “I highly doubt that that made everyone go, ‘Oh ok, well then no worries,'” she says. “Cybersecurity is such a hard thing to get right, and unfortunately we’re not even just talking about that. We’re talking about cybersecurity mixed with this perception/trust issue.”

It didn’t take long for President Donald Trump, his family, and his supporters to exploit the situation to spread disinformation and raise questions that sowed doubt. And it wasn’t just Trump: As the night unfolded, Vice President Joe Biden’s campaign sent a letter to the Iowa Democratic Party highlighting “considerable flaws” in the process and demanding an “full explanations and relevant information regarding the methods of quality control you are employing” before official results were released. On Wednesday, a senior Biden advisor wouldn’t answer when repeatedly asked in a live television interview whether the campaign thought the results slowly being reported by the state party were accurate. Allies of Bernie Sanders have also spread unsubstantiated claims of rigging. It didn’t help matters when the Iowa Democratic Party released a set of results on Wednesday afternoon, only to have to shortly re-release the numbers after mistakes were noticed and circulated on Twitter.

One of the main goals of the 2016 Russian operation, according to multiple US government reports and analyses of the operation, was an attempt to create doubt about the race’s outcome. But who needs the Russian government or a foreign adversary when the president and other self-interested parties are willing to do it for them?

As Joshua Geltzer, a former National Security Council lawyer recently told Rolling Stone’s Andy Kroll, “There’s a counterintelligence threat coming from inside the White House…How do you guard against that?”

While Iowa’s meltdown seems to simply be about the reporting of the results, and not the actual vote totals themselves—the state party’s caucus system produces voluminous paper records, which are being used to verify numbers—experts have warned about the indelible impression early false information can create, even if eventually or quickly corrected. In September 2019, Alex Stamos, who headed up Facebook’s initial investigations of Russian meddling while serving as its chief information security officer, wrote a blog post fleshing out a vision of what he feared could take place in the 2020 election. Stamos imagined a series of events in which CNN and Fox News reported completely different winners from Wisconsin as a result of “subtle manipulation of the intermediate counting systems, websites and data links providing vote returns.” As the scenario went, even though the networks quickly retracted their projections, the incorrect results had been widely tweeted by hacked Twitter accounts representing anchors at both networks, leaving a “an enduring impression”; as a result, Stamos wrote that polling would show that not only did “78 percent of Americans believe the election was stolen”—they couldn’t agree who won.

On Tuesday, Stamos tweeted out a link to his 2019 post, warning that the “largest external risk to American democracy is an attack that combines a technical assault against our widely distributed and poorly secured election infrastructure with disinformation that American partisans will happily amplify.”

While Stamos’ thought exercise takes these concerns to their logical extreme, national security experts do worry some version of them could one day play out. Neil Jenkins, a former Obama Department of Homeland Security cybersecurity official, headed up a war room that monitored threats on Election Day 2016. In 2018, he told CBS News that results reporting was a prime focus: “[An attacker wouldn’t be] effecting the certified official results,” he said, but added that “one of the worst case scenarios would be the media reporting on a projected winner on the night of and then finding out a couple days later as certified results come in that it’s someone different. All of those things would be extremely disruptive to the American public.”

Michael Daniel, a former Obama White House cybersecurity official who now runs the Cyber Threat Alliance, says disinformation based on unreliable results reporting was “absolutely” something the government was concerned about and game-planned for ahead of the 2016 election. While paper records ensure correct results can eventually be made public, “in the meantime it’s just giving complete fodder for all sorts of disinformation,” he says. “When you go into a general election where the partisan edge will be much sharper, the potential for sowing doubt and discord becomes even higher.”

“What happens if somebody manipulated it so that CNN ends up making a call on a state, but then they have to walk it back?” Daniel said. “There are those states that are close, and what if you make a call that goes in the wrong direction?”

While reporting suggesting technical issues are at the root of Iowa’s dysfunction, alongside the fact the party has a paper trail, have both dulled claims of intentional manipulation, Daniel warns that “it’s not very hard to construct scenarios where it’d be a lot harder to stamp out those conspiracy theories.”

“Imagine a more subtle situation where we can’t figure out why it’s not working, we can’t figure out why our numbers are off,” Daniel says. “That would just feed the conspiracy theories and it will lead to lingering concerns about ‘Was all of that legitimate in the first place?'”