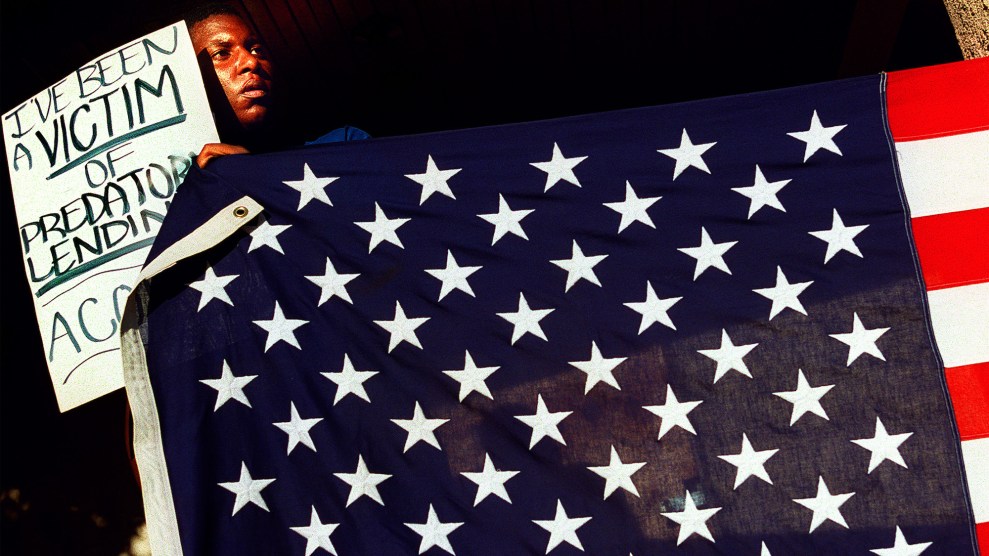

Donte Bruce holds the US flag during a 2000 march in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles to demand fair housing for low-income communities.Wally Skalij/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

Redlining is widely seen as the source of the vast disparities in housing and homeownership between white and Black Americans. Denied access to government-backed mortgages, Black people were consigned to areas of low investment in city centers during boom times in suburbia. It would stand to reason, then, that the end of government-sanctioned redlining, with the 1968 passage of the Fair Housing Act and the Housing and Urban Development Act, would have begun to reverse housing segregation and inequality. But in fact, writes Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor in her new book Race for Profit, that was when things started to get worse.

There were two problems with the new government effort to insure mortgage loans to low-income African Americans in inner cities. First, the existing conditions—the resistance of exclusive white suburbs to any influx of African Americans, the wealth gap—made it just about impossible for the urban poor to move to areas of greater opportunity. And second, the government, less than fully committed to actually fair housing, all but abdicated responsibility for the program to the private sector. That meant that national housing policy was shaped in large part by unscrupulous lenders who saw profit in making risk-free loans to Black buyers for overpriced, dilapidated homes with serious undisclosed damage.

Low-income African American neighborhoods were thus annexed into government homeownership programs that weren’t set up to help them. Taylor calls this process “predatory inclusion.” The result was the further crumbling of the urban core, crippling debt for buyers tricked into homes that should never have been approved for loans, and extractive profits for the private sector.

These issues haven’t gone away. In the 2020 presidential race, which has featured more debate over housing policy than any other in modern US history, Democratic candidates have proposed various forms of reparations to address the lingering effects of redlining. Mother Jones caught up with Taylor to discuss the problems of the past and the solutions of the present regarding the country’s deepening housing crisis.

The underlying implication of your book is that we’re missing the point in our debates over government housing programs. Where have we been getting it most wrong?

I think the biggest problem in the last 50 years is connected to the US hinging the production of affordable housing to the private sector. This presents a couple of problems. One is the historic role of the real estate industry and the banking industry in racial discrimination against African Americans. The whole notion of housing value in the US is deeply connected to notions of race. In fact, the further housing is located away from African Americans, the more it accrues in value. And so federal policies yoking housing production to this type of industry, when Black people are disproportionately among the housing insecure, is a recipe for problems.

The second issue is more fundamental, which is: Public policy, in the best-case scenario, is intended to protect the public’s welfare. Private enterprise—their objective is to make a profit. So those are two opposing objectives.

That’s interesting, because there’s a growing consensus, on the right and among many on the left, that deregulation is needed to build more housing—that with looser zoning restrictions, the private market will build more housing and make housing more affordable in the long term.

It’s a ridiculous idea. Government is the only entity that can deal with the profound lack of housing for millions of people. It’s the only entity that can actually match the scale of the problem.

I also think there’s a way in which the default to the private sector has helped undermine the capacity of the state to resolve these problems. By taking out money and resources, it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy that government is inefficient and ineffective and what we really need is the innovative expertise of the private sector. That mythology comes from a constant gnawing away at the resources that the state has to solve this problem.

You must have been pleasantly surprised to see solutions for formerly redlined neighborhoods taking on prominence in this presidential campaign.

Yeah, although I think—on the one hand, yes, it’s good that housing issues are not taking a back seat. But I do think that some of the specifics raise more questions.

So let’s drill down into that. Elizabeth Warren and Kamala Harris both proposed something similar to what you describe in the book: giving mortgage assistance to residents of formerly redlined areas. Would this cause the same problems as in the late 60s?

Well, it reinforces a central problem, which is segregation. There are two issues. One is that some of these historically redlined neighborhoods are actually gentrifying. So because there’s no race-specific language in these sorts of legislation, it’s not clear who would actually be benefiting from these low-interest mortgages.

The second problem is, in areas where they’re not gentrified, where they remain low-income segregated neighborhoods, what does it mean to guarantee someone the right to buy a house in an area where it won’t appreciate in value? That’s the whole issue in homeownership: It’s supposed to be an asset that accrues in value over time, that through its equity allows you to finance your children’s college education, that allows you to weather an unforeseen economic crisis, that allows for a comfortable retirement. So if a house is not in an area where it can develop equity over time and instead becomes a debt burden, then I’m not sure what the benefit is.

Is there a simple fix that would improve these policies?

No. These are complicated issues, and everyone wants a quick fix. Everyone thinks that if we tweak this or that, these are easily resolved issues, but they’re not. That doesn’t mean there aren’t things that could be done. The US could actually enforce its own civil rights laws regarding racism and housing discrimination, which this government has never done.

Just a couple weeks ago, Newsday concluded a three-year investigation that showed the pervasive racism and discrimination of real estate agents in the Long Island housing market. The question is: Why is a newspaper doing housing testing and not the federal government?

For the things that can be easily done, we don’t do those. That’s the easy thing to do. The more difficult thing is, people talk about the market as this colorblind space where all things are possible. But in reality, the market is us, and so the market then reflects all of the discriminatory ideas about how value is constructed that exist in society at large.

I want to come back to this question of geographic targeting. It seems like you’re damned if you do, damned if you don’t. If neighborhoods have gentrified and are now mostly white or Hispanic, you’re not helping African Americans who have suffered from housing racism. If you’re helping areas that remain mostly Black and poor, you reinforce segregation. So is trying to target certain areas just a mistake?

I think in a racialized market, it’s an invitation to problems. In some ways, it reflects the dynamic that could have been unleashed in 1968. The Fair Housing Act was supposed to open up the suburbs to allow low-income housing to be built there, which would have opened the entire market to African Americans. Something like that would mean that you’re not just consigning Black people to segregated, depreciating areas. If you did something like that, you would witness the absolute hysteria of white homeowners in those exclusive outlying areas rise up to prevent it.

The other question is whether homeownership actually ought to be the goal.

Right. That raises the question about what it means to live in a society where the quality of one’s life is often determined by the ownership of this asset that’s not equally available to anyone. If you have access to homeownership as an appreciating asset, then it’s like you have your own private welfare state. And if you don’t, you’re left to the underfunded, anemic public services that are left for everyone else. Black homeownership is now at a 50-year low. It’s down to 40 percent, with no apparent recovery in sight. It’s as if we’ve just accepted this inequality that’s embedded in our society.

Okay, I know you said there’s no quick fix, but let’s say you look at the Democratic presidential field and decide it isn’t crowded enough and jump into the race, and on January 20, 2021, you’re president and you’ve got Congress’ backing. What’s the first thing you do to address housing inequality?

The first thing I would do is draft Bernie Sanders’ housing plan. I think the plan for 10 million units that are developed, built, and managed by the state, that are out of the realm of the private sector, is an immediate thing that can be implemented.

We call this a housing crisis, but there’s been a lack of affordable, safe-and-sound housing in cities for more than 100 years. And so this is a chronic problem. The first thing I think we could do is create a field of housing that is removed from the private sector that could immediately solve millions of people’s housing crisis.

The second thing is enforcing the civil rights laws that exist on the books that would open up housing opportunities for African Americans. There have been studies that show that Black people pay more for rent in neighborhoods where white people are than white people are paying because of all the perceptions that Black people present a risk.

Those two things are starting points. But there’s no reason why we would have to stop at 10 million units. There’s a way in which the federal government could produce an enormous amount of housing in the country that would take the burden of affordability off the backs of poor and working-class people.

Thanks so much. Let me know when you launch that campaign.

Okay!

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.