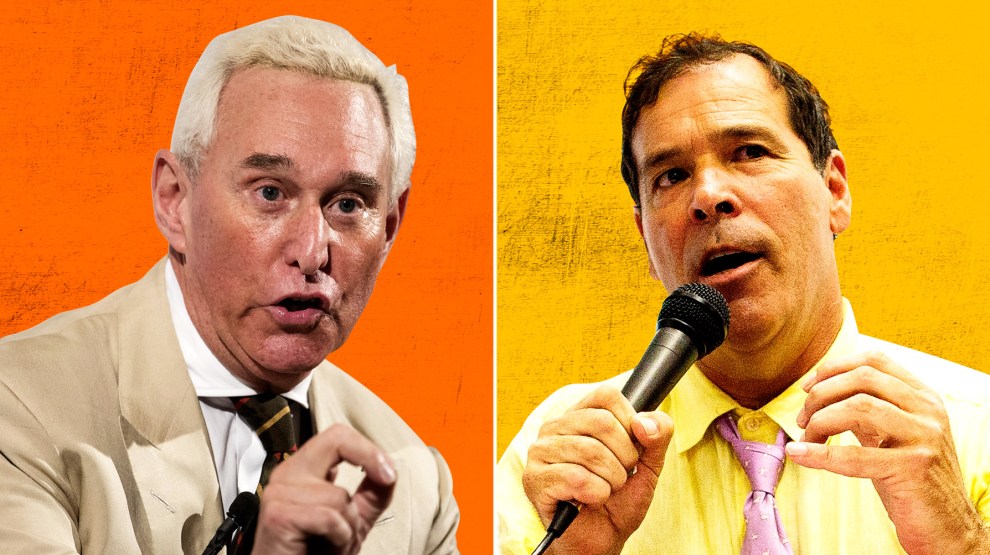

Roger Stone arrives with his wife Nydia for his trial at the E. Barrett Prettyman United States Courthouse on November 7, 2019 in Washington, DC.Win McNamee/Getty Images

Get your news from a source that’s not owned and controlled by oligarchs.

Sign up for the free Mother Jones Daily.

In a federal courtroom in Washington, DC, Thursday, jurors heard Rep. Mike Quigley (D-Ill.) as he questioned Roger Stone, the longtime associate of President Donald Trump. Quigley wanted to know how Stone had communicated with an intermediary who, Stone claimed, had in 2016 helped him learn what WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange was planning to do with stolen Democratic emails.

“Over the phone,” Stone responded.

“Did you have any other means of communicating with the intermediary?” Quigley asked.

“No,” Stone said.

The back-and-forth came from an audio recording of Stone’s interview with the House Intelligence Committee on September 26, 2017. Stone, prosecutors argued Thursday, was lying. Under questioning from a government lawyer, former FBI agent Michelle Taylor testified that Stone had exchanged 72 written communications—texts and emails—on the very day of his House testimony with Randy Credico, the former radio host and comedian. After initially refusing to name him, Stone told the committee in October 2017 that Credico was his intermediary with WikiLeaks. Between June 2016 and September 2017, Stone and Credico exchanged thousands of messages, according to a chart presented by prosecutors Thursday. That includes 253 messages in October 2016, the month WikiLeaks began publishing emails stolen from Hillary Clinton campaign chairman John Podesta.

The Stone-Quigley exchange was one of five audio clips prosecutors played on Thursday in which Stone denied having written records of his contacts with his intermediary, having text messages related to the hacked Democratic emails, possessing messages related to Julian Assange, or having other records relevant to the committee’s investigation into Russian interference.

In addition, prosecutors say Stone’s claim that Credico was his main backchannel to Assange was itself a lie. In fact, Jerome Corsi—a right-wing conspiracy theorist who worked with Stone to help Trump in 2016—provided Stone with what Corsi said was inside information on Assange’s plans weeks before Credico shared other information about WikiLeaks. Stone also had written communications with Corsi that he failed to turn over to the committee.

Asked during his 2017 interview by Rep. Adam Schiff (D-Calif.), then the committee’s ranking member, if he had ever emailed or texted his WikiLeaks contact, Stone said, “He’s not an email guy.”

This is the crux of the government’s case against Stone, who is charged with making false statements to the committee and committing obstruction of justice and witness tampering. And prosecutors appear to be making a persuasive argument.

Stone’s defense, outlined by his lead lawyer, Bruce Rogow, is that because the committee’s investigation was launched to focus on Russian interference and Stone did not knowingly collude with Russians, he did not consider the records he had to be relevant to the committee’s probe, based on how he understood its parameters. Stone’s “state of mind undermines any argument that he did this in a conscious, evil, purposeful way to mislead the committee,” Rogow said in his opening statement Wednesday.

Stone also told the committee that he had not communicated with the Trump campaign about WikiLeaks. But prosecutors have cited three phone calls between Stone and then-candidate Donald Trump. One came on the same day that the Democratic National Committee announced that it had been hacked by Russia. Another came just an hour before Stone asked Corsi to travel to London to meet with Assange. Stone communicated explicitly about WikiLeaks with Steve Bannon, the Trump campaign’s CEO, prosecutors say. And Stone emailed Paul Manafort, chairman of the Trump campaign until mid-August, in apparent reference to WikiLeaks, prosecutors revealed Wednesday. On Thursday, prosecutors displayed a chart showing extensive contacts between Stone and senior Trump campaign officials. For example, Stone had 25 telephone conversations with Manafort in August 2016, according to the chart.

Prosecutors aren’t simply painting Stone as a liar. They also took time Thursday to portray him as a jerk. Much of the evidence they presented related to Stone’s interactions with Credico. In October 2017, Stone told the Intelligence Committee that Credico was his intermediary with WikiLeaks. This wasn’t really true. Starting in late August 2016, Stone asked Credico, who was friendly with a WikiLeaks’ lawyer, to confirm information Assange had announced publicly about his plans, and pushed Credico to seek other information. But Stone had earlier received seemingly more significant information from Corsi. On August 2, 2016, Corsi—who was in Italy at the time after traveling to London—emailed Stone: “Word is friend in embassy plans 2 more dumps. One shortly after I’m back. 2nd in Oct. Impact planned to be very damaging.” Stone immediately began touting those messages. In other words, Corsi was Stone’s original and most important connection to WikiLeaks—information that Stone hid from the committee.

After naming Credico in a letter to the committee, Stone began a campaign, via emails and text messages, to get Credico to go along with his story. Stone emailed Credico what he said were portions of that letter, as an apparent courtesy. But prosecutors revealed on Thursday that Stone had drastically altered the excerpts he sent Credico, adding elaborate praise for Credico.

The excerpts that Stone sent Credico said Stone had turned his attention to the emails WikiLeaks possessed after noticing the “landmark interviews” that Credico, who hosted an AM radio show in New York, had conducted with Assange. That was not in the real letter Stone had sent to the committee, Taylor testified. The excerpts that Stone sent Credico said Stone’s claim that he had a backchannel to Assange was “a bit of salesmanship.” That also was not in the real letter that Stone sent to the committee. In addition, Stone indicated to Credico that his letter to committee had said Credico “confirmed a June 21 tweet and remarks by Mr. Assange.” The real letter to the committee gave Credico a bigger role and said he had “offered information about WikiLeaks.”

Stone appears to have used these phony excerpts to downplay the significance of his claim that Credico was his intermediary.

In late 2017, Stone turned his attention to convincing Credico not to cooperate with the House Intelligence Committee, or with other investigations, including special counsel Robert Mueller’s probe. Stone encouraged Credico to “do a Frank Pentangeli” imitation. That’s a reference to a character in the movie

Godfather Part II who reverses his plan to testify against organized crime boss Michael Corleone and lies to Congress after Corleone arranges to have Pentangeli’s brother brought from Sicily to the hearing. In 2018, as Credico began contradicting Stone in appearances on television and in interviews with

Mother Jones, Stone bombarded Credico with insults and what prosecutors say were threats aimed at discouraging Credico from cooperating with Mueller or other investigators. “Prepare to die cock sucker,” Stone

messaged Credico on April 9, 2018.

Stone told Mother Jones in a text message last year that he was not threatening Credico and that he wrote those words because Credico “told me he had terminal prostate cancer.” Credico said he didn’t have prostate cancer and that Stone’s message “was a threat.”

Stone’s defense must still present its case. But the trial has not started well for the famed dirty trickster.