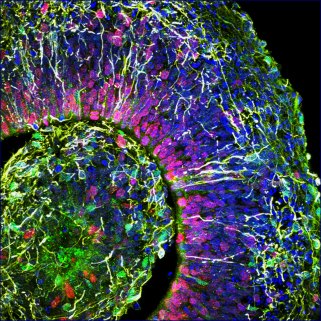

These organoids are 10 months old and about the size of a pea!Muotri Lab-UCTV

For the first time, scientists have detected brain waves similar to those of a pre-term baby in miniature, lab-grown brains.

The results, published Thursday in the journal Cell Stem Cell, have big implications for the medical field. Access to human brains are a consistent barrier to studying conditions like Alzheimer’s, autism, or schizophrenia; for obvious reasons, infant brains are even more difficult to obtain. So models that are grown from stem cells like these mini-brains (known to scientists as “cortical organoids”) may offer a solution.

“It is a model,” Alysson Muotri, a professor in the School of Medicine and director of the Stem Cell Program at UC-San Diego, and an author on the study, tells Mother Jones. “Since we cannot see, we cannot measure [activity in an embryo’s brain], we have to rely on this model.” For example, it may help scientists understand the effects of nicotine, pollution, or pesticides on infants’ development, he says.

It’s not the first time scientists have grown miniature brains in the lab. Researchers have been growing brain tissue for about a decade, according to Muotri. But what’s new is that these mini-brains are the first to show human-like brain activity. “That’s the big excitement about the study,” says Nita Farahany, an ethicist and legal scholar and a professor at Duke University School of Law. “[It] is showing that these organoids have functional activity in the brain that is developing over time and changing over time and becoming more organized over time.” The results would suggest, she says, the possibility for organoids to become “even more organized over time to look like what our brain activity looks like.”

A cross-section of a brain organoid. Each color marks a different type of brain cell.

Muotri Lab-UCTV

To get these unprecedented results, Muotri and his colleagues grew hundreds of brain organoids over 10 months, starting from single stem cells. The stem cells multiplied over several weeks and eventually self-assembled into tissues, about the size of a pea, which spontaneously developed infant-like brain waves. When a computer compared the organoids’ brain waves to pre-term infants’ brain waves, it couldn’t differentiate between the two, suggesting that the organoids’ development is very similar to that of an infant.

The mini-brains can be kept alive for years, Muotri says, but by about 10 months, the brains’ activity starts to plateau. In other words, these organoids will not grow into fully-functioning brains. But that may not be as far away as you’d think: Muotri’s team plans to take the project further by working to grow organoids that model a mature human brain. They also hope to grow organoids using stem cells from people with autism and epilepsy, to see if those develop differently.

But the research raises some clear ethical concerns. It’s unlikely that these organoids have consciousness or self-awareness as you or I do, but as Farahany pointed out in 2018 letter in Nature, there really isn’t a way to reliably measure consciousness in brain organoids; the mini-brains can’t say whether they are self-aware or not. “Is it even possible to assess the sentient capabilities of a brain surrogate?” she and her co-authors ask. “What should researchers measure? If appropriate metrics can be developed, how do investigators decide which capabilities are morally concerning?”

If pre-term babies have some level of moral status, she says, perhaps these mini-brains should too. For instance, imagine you want to see if it’s possible to cause pain in an organoid, she says. “In the same way that with a preterm infant, you wouldn’t just shock it with pain—you’d give anesthetics or things like that.”

Muotri agrees. If they can prove these organoids have “even a residual embryonic signal of any conscious activity,” he says, it would be important to discuss the tissues’ moral status and develop regulations around it, similar to the regulations around animal research. “Animals have consciousness,” he says. “And we can use them for research, but there are regulations. I think brain organoids might go down the same pathway.”

On the flip side, says Farahany, “There is an ethical imperative that this research go forward” because it may help treat disease and alleviate human suffering. “Ethicists have as much of a duty as the scientists to be working in partnership together to define what the next step should be.”