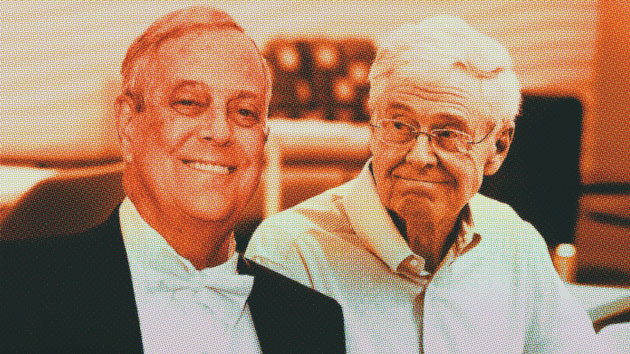

Mother Jones illustration; Michel Delsol/Getty; Phelan M. Ebenhack/AP

David Koch, who died Friday at 79, knew he was living on borrowed time. And for nearly three decades, time was generous with the loan.

On February 1, 1991, he was in the first-class cabin of USAir Flight 1493 when the Boeing 737 collided with a SkyWest commuter flight immediately after landing. “My god, I’m going to die!” he thought to himself as thick black smoke engulfed the cabin. Koch made it out, but nearly a quarter of the passengers on his flight perished. The following year, David, who with his brother Charles transformed their father’s oil and cattle ranching company into a $110 billion conglomerate, experienced another close call when he was diagnosed with advanced prostate cancer. “I thought I was going to die, certainly in months, if not in weeks,” he once recalled. Again, he beat the odds. His doctors couldn’t cure him—but they could forestall the disease, employing a variety of treatments over the years to slow its spread. A memorial to Koch posted on the website of Koch Industries did not specify the cause of his death, saying only that he had spent “many years…fighting various illnesses.” Last year, in failing health, he stepped down from his role as executive vice president of the company.

David’s brushes with mortality changed him, and by changing David Koch, who leaves behind an estimated fortune of more than $50 billion, these events played a part in shaping the world. Before these episodes, Koch was a Manhattan playboy known for cruising around town in a Ferrari and throwing hedonistic parties at his homes in Aspen and the Hamptons. (In 1990, he lamented to New York magazine that a fellow New York cad, Donald Trump, had landed Marla Maples before he had the opportunity. “Marla’s a babe. I wish Donald hadn’t gotten there first.”) After the plane crash and the cancer diagnosis, David settled down with a 27-year-old fashion designer’s assistant from the Midwest, Julia Flesher, with whom he would have three children. And he began pouring his fortune—in donations of as much as $100 million at a time—into philanthropy, including cancer research, the arts, public television, and more.

David’s older brother Charles, the chairman and CEO of Koch Industries, released a statement on Friday praising his brother’s “institution changing philanthropic commitments to hospitals, cancer research, education and the arts.” David’s family, in their own remarks, noted that “David’s philanthropic dedication to education, the arts and cancer research will have a lasting impact on innumerable lives—and that we will cherish forever.”

It was in this benevolent, Carnegie-esque mold that David would prefer to be remembered. But, of course, there is another part of his legacy these statements conspicuously left out—David’s role as a conservative megadonor and political boogeyman who was one half of the enigmatic Koch brothers duo.

Together with Charles, he poured millions into politics in a decades-long bid to advance a conservative, free-market worldview, one passed down to the brothers from their hard-charging father, Fred, a founding member of the John Birch Society terrified by what he saw as encroaching communism. In 1980, David Koch ran for vice president on the Libertarian ticket. The party’s platform that year included abolishing Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, and shuttering a host of government agencies including the Environmental Protection Agency, Department of Transportation, Federal Trade Commission, CIA, and FBI. The primary qualification for David’s candidacy at the time was his overflowing bank account—as a candidate, he could spend as lavishly on the campaign as he chose. He infused the campaign with upwards of $2 million, and, ultimately, Koch and his running mate garnered a little more than 1 percent of the popular vote, a high-water mark for a party that had formed less than 10 years prior.

The Libertarian Party run crystallized a role that David would play throughout his life as the public face of Charles’ political projects. It was Charles who had elevated the libertarians from obscurity, funding the movement almost singlehandedly in its early years and co-founding its flagship think tank, the Cato Institute. Similarly, when the tea party emerged during the early years of the Obama administration, thanks in part to the organizational assistance of Koch-created Americans for Prosperity, David, the group’s chairman, was the more visible presence. It was during the Obama-era, as the Kochs ramped up their political operation to fight what they perceived as a socialistic onslaught, that David Koch’s two worlds came uncomfortably into conflict—in one, he was the benefactor behind the renovation of the David H. Koch Theater at Lincoln Center in New York City, a board member of Boston’s WGBH, and sponsor of NOVA, and the man who had ponied up $65 million to overhaul the plaza in front of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. In the other, he was the modern-day robber baron financing climate change denial and an intemperate right-wing movement of anti-regulatory and limited-government activists.

In the crucible of politics, Charles and David’s identities became virtually fused together as the monolithic Koch brothers. But they were far different men. That was evident by looking at the way both billionaires lived, Charles on the Wichita compound, hemmed in by strip malls, where the brothers grew up, and David in an 18-room duplex at one of New York’s most elite addresses, 740 Park Avenue, where a plaque in the marble entryway to his home read: “Toto, I don’t think we’re in Kansas anymore.”

Charles was the visionary and strategist behind their political and corporate empires. David was his loyal deputy, and though an eager participant in both endeavors, his passions seemed to lie elsewhere. When I was working on Sons of Wichita, my biography of the Koch family—there are four Koch brothers, by the way, not two—a Koch Industries veteran summed up their differences this way: “David,” he said, “is a true philanthropist. David’s [giving] is about making the world a better place. Charles’ is about changing the world.”

David’s numerous detractors—some of whom tastelessly took to Twitter today to wish him eternal damnation in hell—would argue over whether David, at least in the political realm, shaped the world for the better, though in other areas his backing has unquestionably done so. In the end, he leaves behind a complicated legacy. His name memorialized at Lincoln Center, at the Met, at a cancer research center at M.I.T., will tell one story; the significant, though less-visible imprint of his giving on our polarized political climate will tell another.